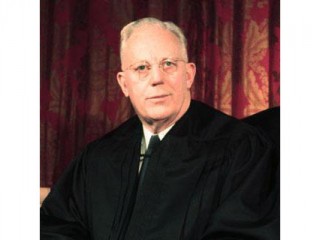

Earl Warren biography

Date of birth : 1891-03-19

Date of death : 1974-07-09

Birthplace : Los Angeles, California

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-03-07

Credited as : U.S. Supreme Court, Governor of California,

During the 16-year term of Earl Warren, a chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, the Court decided a series of landmark cases regarding individual civil liberties and civil rights, particularly for minority groups.

Earl Warren's legal philosophy was opposed to the laissez-faire doctrine that had previously prevailed. His public life before he came to the Supreme Court had been pragmatic rather than activist. He had a natural flair for administration; his prosecutive experience gave him broad insights into the inequities of criminal justice, and he had a realistic understanding of the debilitating effects of racial segregation.

Warren, the son of a Norwegian immigrant, was born in Los Angeles, California, on March 19, 1891, and grew up in Bakersfield. He attended the School of Jurisprudence of the University of California at Berkeley, where he supported himself by working as a law clerk in a local office. Admitted to the bar in 1914, he had a meager practice in California before he enlisted in the Army in 1917.

In 1919 Warren became the clerk to the Judiciary Committee, a potent force in the California Legislature. He rose quickly to deputy city attorney of Oakland and then to deputy district attorney, chief deputy (1923), and district attorney (1925) of Alameda County. In 1925 he married Nina P. Meyers. During his 14 years as district attorney, he prosecuted thousands of criminal cases in an unrelenting fight against crime. Still, he said, "I never heard a jury bring in a verdict of guilty but what I felt sick in the pit of my stomach."

In 1939 Warren began campaigning for attorney general of California. In the midst of this, the tragedy of his life struck; his father was murdered as he sat by the window in the living room. Made more determined by this, Warren pledged to pursue strict law enforcement and to conduct a nonpartisan office. He was easily elected and soon became one of the best-known state attorneys general in the country. He was the resolute foe of the gambling syndicates as well as organized crime.

World War II was in progress, and these were tumultuous times. In 1941 Pearl Harbor catapulted Warren into controversy. California had long been the base of the aircraft industry and was now producing military planes and "liberty ships." At the outbreak of the war between the United States and Japan it was imperative that war materiel production be maintained. Public sentiment against Japanese people reached a frenzy, especially in California, which had over 100, 000 residents of Japanese extraction, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. Violence against these people began to break out, and accusations of disloyalty to the United States were made. Minisubs of the Japanese fleet were off the coast of California; bombs from balloons fell in the forests of Oregon and Washington. The West Coast became a virtual powder keg. Though history may treat the internment of some 112, 000 of these Japanese residents as a brutal violation of the Constitution, Warren made this decision in a desperate hour, and it was approved by the Supreme Court.

Warren was elected governor of California by an overwhelming majority in 1942 and was reelected in 1946 and 1950, serving until he was appointed chief justice of the United States in 1953. A progressive governor, he brought about many statutory reforms, including a unified judiciary, water control, prison modernization, and a new higher education system. In 1944 he was a darkhorse candidate for the presidency of the United States but failed to be nominated. In 1948 he was the vice-presidential running mate of Thomas E. Dewey on the Republican ticket. In a third try for national office, Warren headed the California delegation to the Republican convention in 1952, but Dwight Eisenhower was nominated. Warren became a strong supporter of Eisenhower in the subsequent campaign.

When President Eisenhower appointed Warren to the Supreme Court, he said that he "wanted a man whose reputation for integrity, honesty, middle of the road philosophy, experience in government, experience in the law … will make a great Chief Justice." A great chief justice was long overdue. In its 163d year, the Supreme Court had accomplished little in establishing "equal justice under law" in the actual lives of most Americans. While some of the chief justices who preceded Warren doubtless aspired to give real meaning to the phrase, they could not quite bring it about. Though the due-process clause of the 14th Amendment had been written into the Constitution 85 years before Warren came to the bench, only portions of the Bill of Rights had been applied through that clause against action by individual states. Further, the equal-protection clause of the 14th Amendment had been recognized only in very limited areas. It had not been utilized in the grade schools, in public facilities, or in transportation.

In the field of criminal justice, though lip service had been given to individual rights, the fact is that in state cases poor persons were not furnished a transcript of the trial for appeal or given counsel at any stage of the litigation, save in capital cases. And while the right to vote is the sine qua non of a free society, America had for a century and a half permitted invidious discrimination in legislative reapportionment. Finally, the doctrine of lack of standing in taxpayers' suits had for years acted as an impenetrable barrier to the testing of the constitutionality of many acts of Congress.

The 14th Amendment to the Federal Constitution, adopted in 1868, declared "all persons born … in the United States" to be citizens there of and guaranteed them, among other things, "the equal protection of the laws." However, African Americans struggled long and hard before they obtained these equal rights. It was not until 1954 that an 1896 constitutional rule of "separate but equal" treatment of the races was overturned in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. In his opinion for the Court, Warren declared that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal" and concluded that "in the field of public education the doctrine of separate but equal has no place."

The Brown decision triggered cases attacking segregated public facilities in transportation, libraries, parks, and so forth. Finally, its doctrine was extended in 1964 to places of public accommodation such as restaurants and hotels. The opinion also sparked a tempest of controversy that brought the dawn of a new day in America's economic, social, and political life.

Winston Churchill said that history judges the quality of a civilization by its system of criminal justice. If this be true, American civilization will owe much of its standing to Warren's leadership. Beginning with Griffin v. Illinois (1956), which required states to furnish an indigent criminal defendant with a copy of the evidence adduced at his trial, and extending to Miranda v. Arizona (1967), which afforded counsel to an indigent before interrogation, there was a continual wave of cases that gave substance to the guarantees afforded every individual in the Bill of Rights. These included Mapp v. Ohio, extending the protection against unreasonable search and seizure of the 4th Amendment to actions of the states; Gideon v. Wainwright, giving the 6th Amendment's guarantee of counsel that same coverage; Malloy v. Hogan, protecting the individual from self-incrimination by state action, and Berger v. New York, guarding the privacy of the individual from self-incrimination by state action; and Berger v. New York, guarding the privacy of the individual against eavesdropping by the state.

Like the segregation cases, these opinions aroused a storm of protest. The Chief Justice, as well as the Court, was accused of handcuffing the police, causing a crime wave, and coddling criminals. But the Court continued to follow the principle that when the rights of any individual or group are transgressed, the freedom of all is threatened. In short, it translated the ideals of the Bill of Rights into a strong shield for the individual against both the federal and state governments.

As Warren said in Reynolds v. Sims, "The right to vote freely for the candidate of one's choice is of the essence of a democratic society, and any restrictions on that right strike at the heart of representative government." This right includes not only casting one's vote but also the right to have the vote counted at its full value. Nevertheless, prior to Baker v. Carr (1962), the ballots of rural voters had from 10 to 30 times the weight of those of city dwellers. Warren said in Reynolds v. Sims, "Legislators represent people, not trees or acres. Legislators are elected by voters, not farms or cities or economic interests … The weight of the citizen's vote cannot be made to depend on where he lives."

The impact of the voting cases was tremendous. Thus, there were some 25 cases subsequent to Baker. The political process in representative governments was completely transformed. In the long run the effect of these cases may be more important than those condemning segregation. The right to vote is the citizen's most powerful weapon in a democratic society. Because legislators listened to the voices of voters, the equality of those voices foced them to listen more attentively. One of the basic problems America faced in the city ghettoes included the result of the dominance of the rural voter. The new "one man, one vote" slogan changed the politics of every state in the Union. The decisions of the Chief Justice in segregation, criminal law, and apportionment cases culminated in a campaign to impeach him. He completely ignored it. When asked why he did not fight back, he replied, "A senator or governor may explain or defend his position publicly but not members of the Court. We can't be guided by what people think or say … by public appraisal. If we were we would be deciding cases on other than legal bases."

In his decision in Flast v. Cohen, which the Chief Justice wrote in 1968, he made it possible for citizens to bring "test suits" to the Court. This was one of his last opinions and one of the most important. Because the Court can pass only on legal controversies brought to it, the number of people able to litigate a question is important. Flast was an opening wedge in enlarging the ways and means by which any taxpayer can bring a suit to the Supreme Court. This contributed to opening the door of litigation, bringing forth the greatest surge of citizen participation that any democracy has attained.

Through self-discipline and public experience Warren learned never to permit the clamor of the public or the private pressures of individuals or groups to influence his decisions. Some critics called him a crying liberal, but he classified himself as a conservative-liberal. He had courage, a simple but strong faith in humanity, a practical and varied public experience, and a determination to improve the lot of the common man. As Chief Justice, he extended those horizons in five categories of the law, including racial desegregations, criminal justice, the political process, taxpayer standing to test legislative action, and the all-important field of judicial administration, which enables the courts to function efficiently.

The job of the judge is twofold: first, to determine the rule of law and second, to apply the rule determined. Warren soon found that the legal profession was placing greater emphasis on substantive problems than on administration. As a consequence, court dockets had become congested, the trial bar had decreased in size, and criminal law had become degraded. For over 16 years Warren preached the dogma of improved court administration. In his final address to the American Law Institute on June 2, 1969, he summed up the problem in these words, "We have never come to grips with … court administration… . We should make bold plans to see that our courts are properly managed to do the job the public expects … We must do everything that modern institutions these days do in order to keep up with growth and changes in the times."

In fact, Warren made "bold plans" for the federal system and implemented them. The Judicial Conference of the United States was transformed from a club for chief judges of the courts of appeals into an effective general administrator for the federal courts. Its membership was increased to include trial court representation; the rule making power for federal courts was transferred to it from the Supreme Court; and a complete reorganization of the conferences was effected through a reduction of the number of committees. The administrative office of the federal courts was thus strengthened and reorganized. The Federal Judicial Center, Warren's brainchild, was authorized by Congress and organized into a potent force in judicial administration.

After Robert Kennedy's assassination, Warren feared that nothing could stop Richard M. Nixon from winning the 1968 presidential race. The two men had been bitter enemies since their days as California politicians nearly twenty years before. At age seventy-seven, the chief justice knew that he could not outlast a four-year conservative administration. To prevent Nixon from appointing his successor, Warren submitted his resignation to President Lyndon Johnson on June 11, 1968. He served until 1969. At the request of President Lyndon Johnson, Warren reluctantly headed the commission of inquiry into the circumstances of the assassination of President John Kennedy. He concluded that the killing was not part of a domestic or foreign conspiracy.

He was honorary chairman of the World Peace through Law Center. As chairman of the World Association of Judges from 1966 to 1969, he brought to the judicial forums of the world the message that he had written indelibly into American jurisprudence: only equal justice under law will bring peace, order, and stability to the world.

Warren died on July 9, 1974, in Washington, D.C.