Earl E. Bakken biography

Date of birth : 1924-01-10

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Hennepin County, Minnesota

Nationality : American

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-04-19

Credited as : American scientist, American businessman and philanthropist, Medtronic Inc.

4 votes so far

Earl E. Bakken was born in 1924 in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and grew up there with a strong Norwegian heritage. For all intents and purposes, he was raised as an “only child” since his sister was 18 years his junior. As he had no siblings, he had the run of the house as a boy and a young man, and he used this freedom to great advantage.

Even as a very small boy he appeared to be interested in the electrical wiring of the house and the porcelain insulators. He was constantly tinkering with electrical equipment, experimenting with batteries, electrically activated bells and buzzers, and, finally, robots that would puff cigarettes and wield knives. Finally, it was his mother who encouraged his scientific interest and provided him with the freedom for developing these interests at his own rapid rate.

When Earl E. Bakken was still a shy boy in knee pants, he saw the movie Frankenstein at his neighborhood theater in Minneapolis. It didn’t scare him. It inspired him. “I was fascinated by the idea of combining electricity with medicine,” recalls Bakken.

As a student in secondary school, he was assured by his teachers that it was perfectly all right to be what today is called a “nerd.” Bakken then became the nerd who took care of the public address system, the movie projector, and other electrical equipment at school. To his credit, he did have athletic interests and earned a varsity letter in track. During these formative years, he developed the habits that made him an inveterate reader which has stood him in good stead to the present day.

Despite excellent formal instruction, he recognized that the most important lessons learned were those that were self taught. Since he estimates that the “half life of an engineer’s education is three years,” his life has been one of constant quest and investigation. Through it all, he has faithfully followed his pastor’s advice that it was his responsibility, if he pursued a scientific career, to use it for the benefit of humankind and not for destructive purposes.

Earl Bakken spent three years in World War II in the Army Signal Corps, serving as a radar instructor until 1946. He returned to Minneapolis and earned a B.S. degree in electrical engineering in 1948, then a Masters Degree in electrical engineering with a minor in mathematics from the University of Minnesota. His first wife, Connie Olson, was a medical technologist at Northwestern Hospital in South Minneapolis.

As a graduate student, Earl Bakken visited her frequently in the hospital and finally began spending more and more time conversing with housestaff, attending physicians, and medical students in the hospital. As he became acquainted with the hospital staff, he slowly began providing, at their request, ad hoc medical equipment repairs. Soon it became obvious to him that these hospitals were in need of a person or company dedicated to medical equipment repair.

Earl Bakken started his explorations in psychophysiology in the family garage as a high school student.

The birthplace of Medtronic Company

On April 29, 1949, Earl Bakken and Palmer J. Hermundslie, his brother-in-law, founded Medtronic Inc. and set up shop in a garage in Northeast Minneapolis for the purpose of repairing medical equipment. Medtronic’s earnings for its first month of operation were $8.00. By contrast, Medtronic’s gross earnings for January 2000 were approximately one half billion dollars.

Earl Bakken

Eventually, the company also began selling equipment to hospitals and physicians. The company barely made ends meet for eight years until October 1957, when Dr. C. Walton Lillehei, a University of Minnesota heart surgeon, approached Mr. Bakken and asked him to make a better pacemaker than the alternating current pacemakers then in use in the intensive care units.

Dr. C. Walton Lillehei was pioneering open-heart surgery at the University of Minnesota, and found the PM-65 invaluable in maintaining patients whose hearts did not start beating again after surgery. The pacemaker would keep the heart beating until it healed enough to operate once more on its own. (This was usually a week or two.)

Within four weeks, Bakken produced a small, self-contained, transistorized, battery-powered pacemaker that could be taped to the patient’s chest. Bakken intended this prototype to be used only experimentally on laboratory animals.

He was very surprised to come to the University Hospitals one day, and find it in use on a patient. But Dr. Lillehei said that in tests it had been extremely reliable; and he had no intention of holding off use of the best available technology until Medtronic could make an official production pacemaker. It didn’t take long for the production models to arrive. The external transistorized pacemaker was an important step in the transition from desk-top to fully-implantable units.

Previous to 1957, cardiac pacemakers were bulky, vacuum-tube units operated by AC power. Patient mobility was greatly restricted, and power failures could be disastrous. The Bekken’s wearable, transistorized unit was produced commercially as the Medtronic 5800 pacemaker and liberated hundreds of patients from their power-cord tethers, demonstrating the safety and effectiveness of long-term pacing.

Electronic scheme of the first Bekken’s wearable pacemaker

Soon thereafter, Dr. Samuel Hunter and Norman Roth, a Medtronic engineer, developed a bipolar pacing lead which was more efficient than anything in existence. Following the development of the lead, Medtronic contracted with Dr. William Chardack and Wilson Greatbatch of Buffalo, N.Y., to manufacture and market an implantable pacemaker utilizing the Hunter-Roth lead.

Following these early developments, Medtronic has encountered a few notable failures and many more outstanding successes to become the world’s most prominent medical device manufacturer. In 1984, the National Society of Professional Engineers named the cardiac pacemaker one of the 10 outstanding engineering achievements of the last half of the twentieth century.

A pacemaker is an electronic cardiac-support device that produces rhythmic electrical impulses that take over the regulation of the heartbeat in patients with certain types of heart disease. A healthy human heart contains its own electrical conducting system capable of controlling both the rate and the order of cardiac contractions.

Electrical impulses are generated at the sinoatrial node in the right atrium, one of the chambers of the heart. They then pass through the muscles of both atria to trigger the contraction of those two chambers, which forces blood into the ventricles. The wave of atrial electrical activity activates a second patch of conductive tissue, the atrioventricular node, initiating a second discharge along an assembly of conductive fibres called the bundle of His, which induces the contraction of the ventricles.

When electrical conduction through this system is interrupted, as is the case in a number of diseases including congestive heart failure and as an aftereffect of heart surgery, the condition is called heart block. An artificial pacemaker may be employed temporarily until normal conduction returns, or permanently to overcome the block.

In temporary pacing, a miniature electrode attached to fine wires is introduced into the heart through a vein, usually in the arm. The pacing device, an electric generator, remains outside the body and produces regular pulses of electric charge to maintain the heartbeat. In permanent pacing, the electrode may again be passed into the heart through a vein or it may be surgically implanted on the heart’s surface; in either case the electrode is generally located in the right ventricle. The electric generator is placed just beneath the skin, usually in a surgically created pocket below the collarbone.

The first pacemakers were of a type called asynchronous, or fixed, and they generated regular discharges that overrode the natural pacemaker. The rate of asynchronous pacemakers may be set at the factory or may be altered by the physician, but once set they will continue to generate an electric pulse at regular intervals. Most are set at 70 to 75 beats per minute.

More recent devices are synchronous, or demand, pacemakers that trigger heart contractions only when the normal beat is interrupted. Most pacemakers of this type are designed to generate a pulse when the natural heart rate falls below 68 to 72 beats per minute. These instruments have a sensing electrode that detects the atrial impulse.

Once in place, the electrode and wires of the pacemaker usually require almost no further attention. The power source of the implanted pulse generator, however, requires replacement at regular intervals, generally every four to five years. Most current pacemakers use batteries as a power source, but there has been some exploration of generators energized by radioactive isotopes such as plutonium-238.

Pacemakers come in many shapes and sizes, all of which are small and lightweight (approximately 22-50 grams.) Depending on the patient’s heart condition, the physician will prescribe the number of chambers to be paced and a specific kind of pacing. There are two types of pacemakers, single-chamber and dual-chamber. Single-chamber pacemakers paces either the right atrium of the right ventricle of the heart with one lead. A dual-chamber pacemaker paces both the right atrium and right ventricle of the heart.

The dual-chamber pacemaker is the most common type of pacemaker implanted today. Pacemakers also vary on their type of pacing. A rate-responsive pacemaker is needed when a heart cannot increase its rate according to a person’s needs. It responds depending on a person’s level of activity, respiration or other factors. Each year, more than 400,000 pacemakers are implanted, extending and enhancing the quality life of patients. Sales of pacemaker implantable devices exceed $5 billion per year with the United States as the leader in sales.

The development of Medtronic Inc. into the industry leader to whose example all others aspire can be attributed to much more than Earl Bakken’s engineering genius. His insightful leadership of the company is summed up in the three words he uses as one of his mottos “ready, fire, aim!” That is, a given need is identified; a product is produced or a task is performed, and later refinements are made while the long-term possibilities of the product are debated. He believes one should act on one’s intuition, not overanalyze, and correct the aim later. To quote Mr. Bakken, he believes that “failure is closer to success than inaction.”

Once his business was established, Mr. Bakken became interested in pursuing the historical antecedents of using electricity for therapeutic purposes. In 1969 he asked Dennis Stillings, who worked in the Medtronic library, to see if he could “find some old medical electrical machines.” At that time, according to Mr. Stillings, there was not much of a market in antique medical-electrical devices, and instead, with Mr. Bakken’s agreement, he began looking for early books about the therapeutic uses of electricity. He didn’t know it then, but Mr. Stillings would be working over the next decade with national and international antiquarian book and instrument dealers to build the world’s only library and museum collection devoted primarily to medical electricity.

Mr. Bakken was Medtronic’s chief executive officer and chairman of the board from the company’s incorporation in 1957 until 1976. He was senior chairman of the board until his retirement as an officer of Medtronic in April 1989. Since his “retirement” from Medtronic, Earl Bakken has made some of his greatest contributions to mankind. Specifically, he founded and developed the Bakken Library and Museum which emphasizes the role of electricity in medicine and life.

He has helped develop Medical Alley, a consortium of various manufacturers in Minnesota to develop and promote the area as a hotbed of medical innovation. Earl Bakken is most proud of his endeavors to develop the big island of Hawaii as a “healing island.” He has been instrumental in the development of the North Hawaii Community Hospital, the Five Mountain Medical Community, and the Archeaus Project. The goal of the Archeaus Project is to devise a system that would provide optimum health care for the North Hawaii community by the year 2010.

This health care is envisioned as being very different from the care ordinarily delivered today. Mr. Bakken recognized very early that there was more to medicine and medical practice than simply double-blind studies and statistical significance. He noted that patients fared much better with certain treatments or devices when they were administered by caring and loving physicians. Similarly, the Archeaus Project is based on our knowledge of phenomena such as the difference between the relief of symptoms and true care, the interdependence of the body as well as the mind, the innate ability of the body to heal itself, and the curative effect of a positive relationship between patient and healthcare professionals.

Bronze sculpture of Earl E. Bakken. Located on the plaza of Medtronic, Inc. corporate headquarters, Minneapolis, Minnesota. Dedicated Aug. 31, 1994.

Bronze bust of Earl E. Bakken. Located at The Bakken, A Library and Museum of Electricity in Life, Minneapolis, Minnesota. By George N. Bassett.

Earl Bakken has followed his early pastor’s advice very closely and spent a lifetime serving his fellow man. He created a company that is the envy of the industry and based it on a goal that helps humanity with instruments and appliances that alleviate pain, restore health, and extend life. Representatives and employees of Medtronic Inc. have the reputation of going anywhere at any expense to satisfy a given customer’s needs. Leading by example, Earl Bakken has made the values expressed in the Medtronic Mission Statement “to be recognized as a company of dedication, honesty, integrity and service”–his own values throughout his daily life. Earl Bakken shares the National Academy of Engineering’s 2001 Fritz J. and Dolores H. Russ Prize with Wilson Greatbatch.

Earl Bakken and C. Walton Lillehei, December 16, 1994

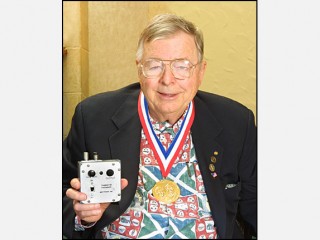

Earl Bakken accepts a rare clinical model of the first wearable pacemaker from Mrs Kaye Lillehei

On February 20, 2001, Earl Bakken and Wilson Greatbatch were honored for their seminal work on the cardiac pacemaker with the Russ Prize, a new national award that was created as engineering’s answer to the Nobel Prize. Established by the National Academy of Engineering, the Russ Prize recognizes advancement of science and engineering achievements that not only improve a person’s quality of life, but that also have widespread application or use.3

The first biennial prize was awarded to Earl Bakken for his development in 1957 of the first wearable, battery-powered pacemaker, and to Wilson Greatbatch for his development in 1959 of the first implantable pacemaker.

Mr. Bakken currently resides in Waikoloa, Hawaii, with his wife, Doris, and remains active in Medtronic.