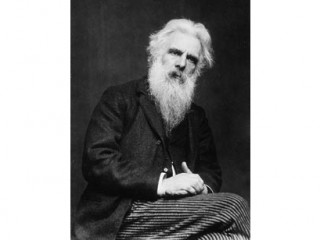

Eadweard Muybridge biography

Date of birth : 1830-04-09

Date of death : 1904-05-08

Birthplace : Surrey, England

Nationality : British

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2011-02-25

Credited as : Photographer, gallop, zoopraxiscope

One of the most innovative pioneers of photography, Eadweard Muybridge is perhaps best known as the man who proved that a horse has all four hooves off the ground at the peak of a gallop. He is also regarded as the inventor of a motion-picture technique, from which twentieth cinematography has developed.

Muybridge was born Edward James Muggeridge on April 9, 1830, in the town of Kingston-on-Thames in Surrey, England. When he was 20 years old, he changed his first name to conform to the Saxon spelling and a possible Spanish lineage; he became "Eadweard." His surname was altered in stages; it went from Muggeridge to Muygridge and finally Muybridge.

Despite his affinity for British antiques, styles, and customs, Muybridge saw his future in the United States. After a brief stay in London, he immigrated to the United States in 1851. He found work as a commission merchant, initially for the London Printing and Publishing Company and later for Johnson, Fry and Company (for whom he acted as business agent). He was involved in the importation from England of unbound books, which were then bound, sold, and distributed in America. By all accounts, Muybridge was a good businessman who, in just a few years, had set himself up nicely.

During this time he made the acquaintance of Silas T. Selleck, a daguerreotypist (a photographer who makes a photo on a plate of chemically-treated metal or glass). Selleck, no doubt, opened up the world of the image to Muybridge. In the meantime, gold fever infected Selleck, who headed west. He eventually established a photography studio in San Francisco, and the lure of California became stronger to Muybridge. In 1855, he decided to join his friend.

By the time Muybridge arrived, the first boom of the great California gold rush had subsided and San Francisco itself was in a recession. An astute businessman, Muybridge still managed to thrive. He opened a bookstore downtown through which he sold material supplied to him by the London Printing and Publishing Company. Above the bookstore he opened an office as the commission merchant for the company.

Muybridge's business opened up new avenues to him. He became a board member of San Francisco's Mercantile Library Association, which promoted reading by sponsoring a library and lectures, and San Francisco's intellectuals frequented his business. He also brought his two younger brothers, first George (who died in 1858), then Tom to San Francisco.

By the late 1850s, Muybridge's attention began to turn away from business. Travel in California and new techniques in photography had spurred his interest in landscape photography. Muybridge was not a pioneer in this field. The photographs of Charles L. Weed, Robert Vance, and Carleton Watkins were already for sale in San Francisco. Still Muybridge hoped to photograph California more extensively than they had done. Subsequently, he gave up both his businesses. The bookstore was turned over to a music publisher, while his brother Tom became the San Francisco commission merchant for the London Printing and Publishing Company.

After giving up his businesses, Muybridge set out on an extended trip to Europe. His plan was to travel east via stagecoach, before sailing abroad. Along the way, the stagecoach crashed and Muybridge was injured. He remained unconscious for several days. His vision and senses of taste and smell were affected. Arriving in New York City, he sued the company, and then sought medical treatment in London. He briefly returned to New York to settle his lawsuit, but eventually returned to Kingston-on-Thames to recuperate further.

While in Kingston-on-Thames, Muybridge befriended Arthur Brown, a man who furthered Muybridge's already keen interest in photography. Muybridge at this time also tried his hand at invention and improvement on already existing patents. He himself sought a patent on a washing machine and though it was never granted, Muybridge did receive other patents in the United States and England.

In his book Muybridge: Man in Motion, Robert Bartlett Haas describes this time period (1860-66) as Muybridge's "lost years." In fact, Muybridge was really developing a plan. He devoted more and more time to his craft just as new photographic techniques were being developed. He eventually decided the United States, as both subject and market, offered the best opportunity for a budding photographer.

Muybridge made his way back to San Francisco, now much changed and even more to his liking. If he had had any second thoughts about returning to his old business ventures, they quickly vanished. He was now a professional photographer, and briefly shared a studio with his old friend, Selleck.

He first concentrated on scenes of San Francisco, a city of approximately 200,000 people in 1870. He began taking cityscape photographs of San Francisco in 1867 and would continue to do so until 1881. Many of Muybridge's early photos were of San Francisco Bay from various vantage points, but he also took numerous photographs of city life, notably the architecture. Among his better known photographs at this time were "Pacific Bank, Sansome Street," "Merchant's Exchange, California Street," "Montgomery Block," "Montgomery Street, north from California," "Maguire's Opera House," "Trinity Church and Jewish Synagogue," "The Cliff House," "Russian Hill from Telegraph Hill," and " Montgomery and Market Street, Fourth of July." These photos reflect the growing city, as it emerged to become the most important cities in California.

In 1872 and 1873, Muybridge began to photograph what has become his signature series, a galloping horse. Legend has it that a $25,000 wager between former California Governor Leland Stanford and a rival was involved, but Muybridge's own account makes no mention of the bet. It is believed that Stanford hoped to use the information to breed and train better race horses, while Muybridge was interested was in animal locomotion. But as the Masters of Photography website noted that "The experiments were interrupted when Muybridge was tried in 1874 for murdering his wife's lover.

In 1872, Muybridge married Flora Stone, 22 years his junior, whom he had met when she had worked as a photographic re-toucher at another studio. Their brief marriage would culminate in one of the city's biggest scandals of the decade. Into their circle came Harry Larkyns, a former major in the British army who in 1873, had become theater critic for the San Francisco Post. Larkyns possessed all of the outgoing qualities Muybridge lacked, and it wasn't long before he had thoroughly charmed Flora.

While Muybridge also returned to his original photographic purpose, taking photographs in America's Northwest, Flora and Larkyns became lovers. Muybridge ideas expanded, and he photographed members of the Modoc tribe, Vancouver Island, and Alaska, as well as produced a series of photographs that followed the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads from San Francisco to Omaha, Nebraska. Meanwhile, back in san Francisco, Flora became pregnant, and Larkyns was rumored to be the true father of her child.

When the rumors as well as the with near undeniable evidence came back to Muybridge, he set out to kill Larkyns who had already fled San Francisco. In October of 1874, Muybridge shot and killed Larkyns. He was indicted for premeditated murder, and his trial was held in early 1875. He was found not guilty after a short trial.

Muybridge decided he needed a change of scenery and decided to take his camera to Central America. He spent 1875-76 primarily in Guatemala and Panama, concentrating his camera lens on cities such as Colon, Panama City, and Guatemala City, as well as the surrounding countryside, which yielded completely fresh subject matter.

While he was in Central America, Flora died and her child, Floredo, was placed in an orphanage. Upon his return to California, Muybridge learned of her death. Though he was convinced he was not the boy's father, he did regularly visit Floredo at the orphanage. In 1877, Muybridge resumed his work with Stanford.

Muybridge photographed Stanford's racehorse, named Occident. The purpose of the photos was to determine whether all four of a horse's hooves are off the ground at some point in a gallop. Muybridge had already developed automatic shutters, which he then set up in a dozen cameras along a Sacramento racecourse. (The Washington Post noted that "Muybridge's studies are so cleanly, almost starkly, done that it's easy to forget the endless drudgery involved.) As Occident galloped past, the horse tripped wires that were connected to the shutters. The photo series of Occident proved that all four of a horse's hooves are off the ground at some point.

In 1877, Muybridge photographed another of his masterpieces. He set up his camera on the San Francisco's famed Nob Hill, where he had already been commissioned to photograph the mansions, and took a panorama of the city using eight by ten-inch plates. The result was a magnificent view of the city on 11 panels that stretched to seven and a half feet in length. Muybridge published this as "Panorama of San Francisco from California Street Hill."

Muybridge was not only fascinated by animals in motion, he was intrigued with devising a method of having photographs depict motion. The Masters of Photography website described this as "stop-action series photography."

He had already experimented with various automatic shutters to quickly capture movement when in 1879, he developed what he initially called the zoogyroscope, which later became known as the zoopraxiscope. As defined by the Masters of Photography website, a zoopraxiscope was a "primitive motion-picture machine which recreated movement by displaying individual photographs in rapid succession."

Muybridge used glass disks with sequential photos on each disk of a horse in motion as the "slides" for his projector. This pioneering method predated Thomas Edison's Kinetoscope and even influenced it. Many now believe that Edison's work was a refinement of Muybridge's, albeit a vastly improved refinement.

Muybridge spent much of his later career at the University of Pennsylvania. He took photographs between 1884 and 1887, demonstrating animal and human motion and movement. The result was Animal Locomotion, published in 1887. The Masters of Photography website described it as "the most significant work was the human figure."