Douglass Frederick biography

Date of birth : 1818-02-18

Date of death : 1895-02-20

Birthplace : Easton, Maryland, United States

Nationality : African-American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-06-09

Credited as : Abolitionist leader, Writer and editor,

0 votes so far

Douglass was born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey in his grandmother's cabin on Holme Hill Farm along Tuckahoe Creek, Talbot County, on Maryland's Eastern Shore in February of 1818. Douglass never knew his exact birth date, but claimed February 14 as his day because his mother, Harriet Bailey, once referred to him as her "valentine." Douglass was the fourth of seven children born to Harriet, a field hand living on a plantation. Douglass was around eight-years old when his mother died in 1825, a year after he was sent to live in the home of his master, Aaron Anthony. Douglass did not know much about his mother, but what he remembered of her remained with him forever. Douglass never knew the identity of his father, though he always maintained that his father was white, possibly his first master, Anthony.

Anthony was the general overseer of Colonel Edward Lloyd's plantation on the Wye River. Douglass was too young to work in the fields, so he ran errands and performed other simple chores. It was while at his master's home that Douglass experienced the hardships of slavery, mostly suffering from hunger and cold.

In 1826, Douglass was sent to Baltimore to serve as a houseboy in the home of Hugh and Sophia Auld, the brother and sister-in-law of Thomas Auld, who was the husband of Lucretia Auld, Anthony's daughter. But it was Thomas Auld who became Douglass's owner following Anthony's death in 1826. His stay in Baltimore over the next seven years profoundly impacted Douglass. It was here that Douglass learned to read and write and received his introduction to the power of the spoken and written word, having purchased the Columbian Orator, speeches collected by Caleb Bingham.

In 1833, Douglass returned to the Eastern Shore to live on Thomas Auld's plantation. The next year Douglass was hired out for a year to a local farmer, Edward Covey, well known as a "Negro-Breaker" or one who had a reputation for reforming recalcitrant slaves. Covey whipped Douglass almost weekly. Douglass, who was now age 16, slave fought back. In Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, Douglass said that the recurring battle with Covey "was the turning-point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood.. . . It inspired me again with a determination to be free." He left Covey's service on Christmas day in 1833 and on January 1, 1834 was assigned to William Freeland. During this period, Douglass held at least two "Sabbath" schools. Of course, it was illegal to teach slaves to read and write, but that did not stop Douglass. He managed to gather some old books for his students. "They were great days to my soul," he continued. "The work of instructing my dear fellow-slaves was the sweetest engagement with which was ever blessed." Still, Douglass was restless. The life of a field hand was more restrictive and difficult than that of a city houseboy; he yearned to be free. It was not long before Douglass plotted to escape. Around the end of 1834, after forging passes for himself and four companions, he made ready to flee bondage. Unfortunately, the plot was discovered and Douglass was jailed in Easton, Maryland. Surprisingly, Douglass was not branded or sold to a slave owner in the Deep South, a fate met by others who tried to run away. Instead he was sent back to Baltimore to become a servant for Hugh and Sophia Auld, with the promise that his master Thomas Auld would emancipate him at age 25.

The Life of a Fugitive

Back in Baltimore in 1836, Hugh Auld hired out Douglass as a caulker in the Baltimore shipyards. For the next two years Douglass stayed in Baltimore, coming in contact with the large, free black community there. That made him more determined to be free. In the meantime, he and five other youths formed the East Baltimore Mental Development Society, a secret debating club where Douglass honed his debating and oratory skills. In time, he would develop a powerful and appealing oratorical style. It was at one of its social gatherings that Douglass met Anna Murray, a free black woman who worked as a domestic. They fell in love and became engaged. Murray later assisted Douglass when he impersonated a sailor while using protection papers he borrowed to facilitate his escape on September 3, 1838.

Upon reaching New York City, Douglass was assisted by David Ruggles, the fearless secretary of the New York Vigilance Committee, an organization which assisted fugitives. At Ruggles's home, Douglass was joined by Anna Murray. They were married on September 15, 1838, in a ceremony presided over by James W. C. Pennington, a minister and fugitive from Maryland. The newlyweds later settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Douglass took the name by which he is popularly known. This union produced five children: Rosetta (b. June 24, 1839), Lewis Henry (b. October 9, 1840), Frederick (b. March 3, 1842), Charles Remond (b. October 21, 1844), and Annie (b. March 22, 1849). Unable to find work in the shipyards because of discrimination, Douglass worked at odd jobs to support his family.

The Beginnings of an Abolitionist Career

In New Bedford, Douglass became a subscriber to the Liberator, a militant anti-slavery weekly newspaper edited by William Lloyd Garrison, an uncompromising abolitionist. At an abolitionist gathering in August of 1841 in Nantucket, Massachusetts, Douglass was unexpectedly called on to speak. Speaking haltingly but passionately, Douglass related his experience as a slave, holding his audience captive. Garrison was among the listeners.

So riveting was his presentation that the officers of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society asked him to become an agent. Douglass accepted and embarked on a lecture tour of the North for the next four years, often in the company of Wendell Phillips, a member of the society and gifted orator. At first Douglass simply related his experiences as a slave but later, as he became more confident in his new role, he lectured about the evils of slavery, presenting the same abolitionist arguments as other members of the society.

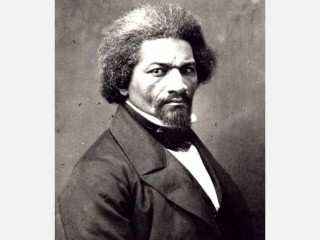

In physical appearance Douglass was an imposing figure on the platform or in person. Douglass stood over six-feet tall, had a solid build, possessed deep-set eyes, a well-formed nose, and a mass of hair that was neatly combed and parted on the side. His rich, persuasive, baritone voice could hold an audience captive for hours and was tuned to the point where all could hear his words loudly and clearly. It was this voice that made Douglass one of the most effective and sought-after speakers of his day.

Douglass was an accomplished author, too. The 1845 Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, Written by Himself, which revealed Douglass's true identity, was a testament to the evils of slavery, detailing its dehumanizing nature and its attempt to crush one's spirit. Most importantly, it showed how its author overcame these hardships and freed himself from physical and mental enslavement.

The book, consisting of 125 pages with introductions by Garrison and Phillips, quickly became a bestseller in reformist circles. Because the book used real names and places, Douglass was in danger of being recaptured. This was one of the reasons Douglass decided to leave the United States and tour the British Isles.

On August 28, 1845, Douglass arrived in Liverpool, England. and spent the next 21 months touring England, Scotland, and Ireland. Besides speaking for the abolition of slavery, Douglass also spoke out on temperance, the repeal of the Corn Laws, Irish home rule, and a plea to the Free Church of Scotland to return money received from pro-slavery Southern Presbyterian churches. Douglass found his audiences receptive and sympathetic. While there, British friends raised money for Douglass to purchase his freedom from Thomas Auld. They also raised money for Douglass to start a newspaper, something he planned to do when he returned to the United States. Although Douglass was given the opportunity to stay and live in England, he realized that his fight to free his people had to be waged in the United States.

The North Star is Born

Douglass returned to the United States in August of 1847 and announced plans to start a newspaper. Although Garrison and Phillips were opposed to the idea, Douglass proceeded with his plans. Five weeks after moving his family to Rochester, New York, the first issue of the North Star appeared. For a short time, Douglass served as co-editor with Martin Delany, the founder and former editor of the Pittsburgh Mystery.

With the publication of the North Star, Douglass came into closer contact with the free black community than as an agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, which mostly consisted of white abolitionists. He developed a deeper identification with other African Americans and used his weekly paper to champion their cause. His paper spoke against slavery and oppression, and its office in Rochester served as a station on the Underground Railroad. In a 10-year span, Douglass assisted close to 400 fugitives by providing them with food, shelter, advice, and comfort before they reached Canada. His most famous "passengers" were William Parker and two other fugitives from Christiana, Pennsylvania, who had killed a Maryland slaveholder who was pursuing his slaves.

Douglass had a close or familiar relationship with almost every known reformer in the United States. Among black abolitionists, Douglass counted as his friends or rivals, such people as Reverend Henry Highland Garnett, Reverend Jermain Loguen, Martin R. Delany, Reverend Samuel Ward, Henry Bibb, novelist William Wells Brown, noted abolitionist speaker Charles Remond and his sister, Sarah Parker Remond, and Harriet Tubman. Douglass worked with most of them, particularly in the National Negro Conventions of the 1840s and 1850s.

Douglass was a true reformer, not only as a fervent opponent of slavery, but one who abhorred all forms of oppression, particularly against women. Douglass also supported prominent persons in the woman's rights movement. He was a close friend of Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, Lucretia Mott, and Sojourner Truth and associated with them until the end of his life. Douglass attended the first Woman's Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, in July of 1848, and remained a staunch supporter of the movement, holding a lifelong commitment to woman's rights.

With the dawn of a new decade, Douglass increasingly saw a need to become more politically active in the 1850s. Douglass had become a close associate of New York abolitionist Gerrit Smith, a Garrison opponent and a political activist. Smith's influence, in part, encouraged Douglass to become a voting abolitionist in 1851. This move, however, would mean breaking politically with Garrison. A bitter feud ensued. For the next seven years Douglass supported Smith's Liberty Party and the new Republican Party, endorsing its candidate, John C. Fremont, for president in 1856.

In the meantime, Douglass changed the name of the North Star to Frederick Douglass' Paper, accepting a subsidy from Gerrit Smith. He also continued to lecture in the North, delivering one of his most famous speeches on July 4, 1852, "What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?," published in My Bondage and My Freedom:

What to the American slave is your Fourth of July? I answer, a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustices and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. ...

Go where you may, search where you will, roam through all the monarchies and despotisms of the old world, travel through South America, search out every abuse, and when you have found the last, lay bare your facts by the side of the every-day practices of this nation, and you will say with me, that, for revolting barbarity, and shameless hypocrisy, America reigns without a rival.

In 1855, Douglass published his second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom, a more complete autobiography than the first. This decade saw several events that moved the North and South closer to war, starting with the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. Many abolitionists were particularly hostile to this act, which denied a fugitive the right to testify on his or her behalf as well a trial by jury. In the round of condemnations against the Act, none was stronger than Douglass's. He told an audience in Boston that if there was an attempt to enforce the law in that city the streets would run with blood. Later, he told an audience in Pittsburgh that the only way to make the Fugitive Slave Law a dead letter was to make a few dead kidnappers. The nation was further divided over the Dred Scott decision in 1857, which declared that blacks had no rights that whites needed to respect.

An event that made war between North and South seem inevitable was John Brown's raid on the federal arsenal at Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, in October of 1859. Douglass had known Brown since 1848, having met him in Springfield, Massachusetts, and they remained cordial friends. The two men, however, differed on strategies for abolishing slavery. Brown advocated violent actions; Douglass chose peaceful persuasion. Even still, Brown stayed in Douglass's home in February of 1858 while perfecting the plans for the raid. In August of 1859, two months before the planned attack, Douglass met Brown in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, where he rejected Brown's invitation to join the attack. The unsuccessful raid on Harpers Ferry ended in Brown's capture; Douglass fled to Canada to escape federal charges of aiding and abetting Brown. From Quebec he sailed to England, where he stayed for six months. Douglass returned to the United States in May of 1860 after learning of the death of his youngest child, Annie.

Fighting for Emancipation

In the spring of 1860, Douglass began to campaign for Abraham Lincoln, the Republican candidate for president. Lincoln's subsequent election to the presidency caused southern states to break away from the Union, a development that Douglass welcomed. He celebrated the news of Southern forces firing upon Ft. Sumter in South Carolina, believing that a civil war was the only way that slavery could be destroyed and his people set free. He also called on Lincoln to enlist black troops in the Union armies, feeling that African Americans should have a hand in their own liberation.

Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, thus freeing all slaves in the rebellious states of the Confederacy. It was then that black soldiers were welcomed to join the Union forces. Douglass became an active recruiter, traveling throughout the North enlisting more than 100 black men to fight with the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, two were his own sons Lewis and Charles. Oddly, Douglass ceased recruiting in 1863 and visited President Lincoln to protest discrimination against black soldiers, particularly because they were receiving lower pay than white soldiers.

In 1863, Douglass had a conference with Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton in hopes of receiving an army commission. In anticipation of receiving the commission, Douglass ceased publication of his paper, called the Douglass Monthly, ending 15 years as an editor. To Douglass's disappointment, the commission never came.

In 1864, Lincoln called Douglass to the White House and asked him to be one of his advisors to plan for his reelection. Douglass was tempted to oppose Lincoln's reelection because of the slowness of his administration in officially making African Americans U.S. citizens; finally he decided to endorse him. In 1865 he attended Lincoln's second inaugural ball and spoke at many "Jubilee meetings" in black communities across the North in support of Lincoln before his assassination.

Douglass endorsed the Republican Reconstruction plans, which included calling for black suffrage throughout the South. He was part of the black delegation that met with Lincoln's successor, Andrew Johnson. The delegation was highly critical of the new president's agenda, and they left the meeting receiving little support from Johnson. Sometime later, the Republican-controlled Congress impeached Johnson and then took over the reconstruction of the nation. Congress ratified the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, giving black men the right to vote. Despite its limitations, Douglass celebrated the passage of the amendment, but split with the women's movement over this issue because the amendment made no provisions for woman's suffrage. Meanwhile, Douglass established the New National Era in Washington, D.C.

Douglass's life between 1871 and 1872 was marked by trials and tribulations. On January 12, 1871, President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Douglass assistant secretary of the commission of inquiry to Santo Domingo (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic). He toured Santo Domingo from January 18 through March 26 and defended President Grant's decision to annex the island. After the trip, Douglass was persuaded that annexation would be useful to both countries. Tragedy struck Douglass on June 2, 1872, when his Rochester home was destroyed by fire, burning important copies of Douglass's newspapers and personal letters. Suspecting arson, Douglass moved his family to Washington, D.C.

In March of 1874, Douglass was named president of the Freedmen's Bank, which was designed to help the newly-freed African Americans deposit their savings. The bank was in deep financial trouble before Douglass became its leader. When the bank failed, however, Douglass bore the brunt of the blame for its demise. Following that fiasco, Douglass closed down the New National Era, and threw himself into his work for the Republican Party. He was rewarded when he was appointed to public office. In March of 1877, President Rutherford B. Hayes appointed him U.S. marshal of the District of Columbia, a first for an African American. In March of 1881 he was appointed recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia by newly-elected President James A. Garfield, another African American first. He held this position for five years. In both positions Douglass took his duties and responsibilities seriously, but despite being appointed by the President himself, he never hesitated to speak his mind about issues that affected black people. He never stopped pushing the nation toward full equality. It was later, in November of 1881, that Douglass published his third and final autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass.

Tragedy again befell the Douglass household when Anna, his wife of 44 years, died after a long and painful illness. Two years later, on January 24, 1884, Douglass remarried, this time to Helen Pitts, his white secretary when he was recorder of deeds. This marriage brought on a storm of controversy. His black contemporaries accused him of selling out. Douglass, though, insisted that his marriage proved that blacks and whites could live in equality under the same roof. Holding no office at this time, Douglass and his wife decided to travel, visiting England, Egypt, France, Greece, and Italy.

After returning, Douglass assisted the Republican Party in campaigning for Benjamin Harrison for the presidency in 1888. After Harrison was elected, he appointed Douglass minister-resident and counsel general to Haiti on July 1, 1889. Douglass was well received by the Haitians, as they were familiar with his career. He remained in that position until January of 1891, when he resigned in protest after American business groups and the U.S. State Department sought to acquire Mole St. Nicholas over the objections of the Haitians.

The next few years of Douglass's life were quiet. From 1892 until 1893 he served as commissioner for the Republic of Haiti at the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago. Douglass also joined Ida B. Wells Barnett, the fiery journalist and anti-lynching activist, in forcefully speaking out against lynching. In 1893 he also introduced Wells's pamphlet, The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago. In January of 1894 Douglass delivered his last major speech "Lessons of the Hour," in which he strongly denounced lynching in the South.

Douglass delivered a speech to a meeting of the National Council of Women, held in Washington, D.C., on February 20, 1895. Later that evening, at the age of 71, he suffered a heart attack and died at Washington home. His body was buried in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York. In 1955 the National Park Service of the U.S. Department of the Interior declared his home, located in the Anacostia section of Washington, a national shrine.

A Lasting Legacy

At times Douglass agreed with many, particularly when it came to emphasizing race pride and economic self-reliance among African Americans. Other times, they disagreed and, sometimes, he found himself in the minority. Douglass disagreed with such influential people as Martin Delany and James T. Holly over the issue of integration or separation. Douglass believed that African Americans should become a part of American society in order to build a colorblind society. Douglass stood virtually alone on his position on the exodus of black people to the state of Kansas and other states in the Midwest to escape racial violence and economic oppression in the 1870s and 1880s. He believed that the government should protect the lives of its black residents to the point that migration for the sake of a better life would be unnecessary. In time, he realized that the protection was not there and modified his view.

Douglass was honored by many--black and white--because he was dedicated to uplifting all oppressed people. He never restricted himself to addressing one issue that affected humanity, but a variety of concerns. He recognized that America's strength depended on full participation of African Americans in society. He also declared that that America's treatment of its black citizens would be the litmus test of whether or not America was a true democracy. Because of these insights, Douglass was one of the most influential African Americans during the last two centuries, and his legacy lives on.