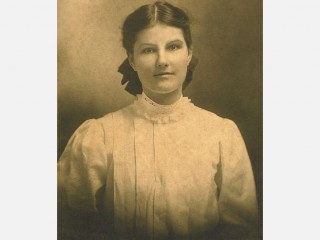

Dora Smith biography

Date of birth : 1893-02-14

Date of death : 1985-01-28

Birthplace : Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-02-24

Credited as : Educator, researcher and lecturer,

The American educator Dora Smith researched, lectured, and wrote extensively about language arts and English curricula in elementary and secondary schools. Dubbed "The First Lady of the United States in the Teaching of English," Smith was also internationally acclaimed as a scholar and consultant.

Dora V. Smith was born on February 14, 1893, to Scottish immigrant parents in Minneapolis. She received her B.A. from the University of Minnesota in 1916 and began her professional career as a high school English teacher in the rural community of Long Prairie, Minnesota. Smith received her M.A. from the University of Minnesota in 1919 and her Ph.D. from the same institution in 1928, working in the interim primarily as an English teacher and supervisor of student teachers at University High School in Minneapolis.

Upon receiving her doctorate, Smith joined the faculty of the University of Minnesota, teaching courses in children's and adolescent literature as well as English and language arts methods. In the early years of her academic career, Smith spent a year in residence at St. George's College at the University of London (1920-1921) and another at Teachers College at Columbia University (1928-1929). In later years she taught summer sessions at Columbia, the University of California, and the University of Hawaii, among others.

Smith's thesis on the effects of class size on high school English teaching methods and outcomes, published by the University of Minnesota Press in 1931, anticipated many of the later controversies over instructional techniques and grouping practices. After comparing freshman English students in two "small" classes of 20 with matched groups of 20 students in two classes of 51, Smith concluded that students in the larger classes performed better in reading literature than their counterparts in smaller classes. She found that successful teachers of larger groups used discussions and projects rather than recitations and worksheets and divided their classes into smaller groups for such tasks as correcting homework, investigating topics, and presenting reports. Long before Robert Slavin's work on cooperative learning and Benjamin Bloom's on mastery learning, Smith advocated having students coach and instruct each other in mixed-ability groups while the teacher provides more intensive individualized instruction to students who need this help.

Smith was interested not only in instructional technique, but also in curriculum content. From 1936 to 1937 she served as a consultant to the New York Regents, investigating that state's response to the challenge of educating college-bound and non-college-bound students from a variety of social classes and settings. Again anticipating contemporary debate, she expressed concern about allowing tests such as the Regents' Examination to drive curriculum decisions.

Smith pursued her interest in curriculum through the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE). She served as NCTE's president in 1936-1937, then undertook, in 1945, the enormous task of directing and editing the National Council's five-volume series on English curricula from kindergarten to graduate school. The outcomes of the English curricula she proposed were consistent with the tenets of progressive education: to encourage students at all levels to develop solid personal values, understand themselves and others, establish personal reading habits, and learn to think critically, an especially important skill for citizens in a democracy. Throughout the series, she emphasized the importance of beginning where students are and keeping their individual and age-related characteristics in mind.

Smith was no extremist when it came to the educational controversies of her day; instead she consistently advocated flexibility in approach in order to best serve the needs of the individual child. In response to Rudolf Flesch's scathing Why Johnny Can't Read (1955), for example, she rebutted the notion that phonics alone could improve reading ability, yet she did not believe that sight word recognition or, as it was popularly known, the "look-say" method of reading instruction could stand alone either. She believed there was a place for basal textbooks in the classroom, but also wanted children to experience the "fun, fact, and fantasy" of real books. As she noted sensibly, "No one method of approaching words will ever suffice…. The business of teaching children to read is too important for us to put all our eggs in one basket."

Smith was similarly flexible in addressing the question of whether students should read "classics" or contemporary children's and adolescent literature. She stated that "no single book is so important as to warrant reading at the expense of the development of a voluntary habit of good reading"; yet she urged teachers to guide students to select higher quality mystery stories than the then-popular Nancy Drew and Hardy Boys series. She suggested that teachers tailor their book recommendations to match the interests and tastes of individual students, noting that the "recommendation of a single book which fills a real need in the life of a child will do more to foster mutual relations of interest and good will than all the prescribed reading lists ever printed."

Smith herself was never far from the real needs in the lives of children: throughout her career she served as a consultant for several major U.S. school districts, including Oakland, California; Los Angeles County; Battle Creek, Michigan; Bronxville, New York; Salt Lake City; Austin; and Denver. During a sabbatical leave in the mid 1950s, Smith embarked on a year of international travel to Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Thailand, India, Pakistan, Lebanon, Turkey, Greece, and Egypt. Her mission was to find modern books about the customs and cultures of these countries, many of which were just emerging from a period of colonial rule, for American school children. In a newspaper interview prior to the trip, Smith said, "We know the fairy tales and beast fables of many countries, but we have few stories of how children in other countries live, feel, and think today. We do not want our boys and girls to have the notion that the children of India, for example, help to kill giants and go out on errands of magic in company with the genie."

After more than 40 years of scholarship and service in the areas of curriculum development, reading habits, and children's literature, Smith retired from the University of Minnesota as a full professor of general education in 1958. That year she received the highest honor of the National Council of Teachers of English—the W. Wilbur Hatfield Award—for her "long and distinguished service to the teaching of English in the United States." She remained highly productive in her retirement years: her book Fifty Years of Children's Books, 1910-1960 was published in 1963 and a compilation of her thought entitled Selected Essays came out in 1964. Smith died on January 28, 1985, at the age of 92.

Robert C. Pooley provides biographical information in his foreword to Selected Essays (1964); that book also serves as a good introduction to Smith's work in language arts and English education. The University of Minnesota Archives has additional biographical material on file, including newspaper clippings and a record of Smith's activity within the university community.

Smith's Communication, The Miracle of Shared Living (1955) is intended for general audiences. It emphasizes that communication skills are critical for full and meaningful participation in a democratic society. Fifty Years of Children's Books (1963) still reads relevantly, though it, of course, does not take into account later trends in children's literature. Numerous shorter pieces by Smith may be found in education journals such as English Journal, Elementary English Review, School Review, and Review of Educational Research.