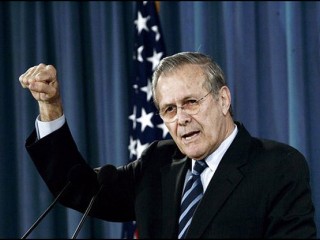

Donald Rumsfeld biography

Date of birth : 1932-07-09

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Chicago, Illinois, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-09-21

Credited as : politician, U.S. Secretary of Defense,

0 votes so far

Born in Chicago, Illinois, to a real estate broker and homemaker, Rumsfeld's childhood was notable for an innate charisma that drew people to him. He showed an early interest in politics and the world around him when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. Being a nine-year-old boy and seeing his father put aside his career to join the Navy left a deep impression on him that would shape his character and lead to a career in politics.

The young Rumsfeld was a hard worker, never happy to sit on his hands for even a moment. By the time he was a teenager he had held down 20 part-time jobs ranging from delivering newspapers to gardening. During high school he met a girl named Joyce who he would go on to marry. With high energy, focus, and excellent grades he was accepted to Princeton on academic and Naval Reserve Officer Training Corps (NROTC) scholarships.

In 1954, he started service to the U.S. Navy as a flight instructor. He ended his tenure in 1957 when he transferred to the Ready Reserve. Though he continued his Naval service in flying and administrative assignments as a reservist, he had plans for his career that would put him in a two-piece suit instead of a flight suit.

He joined the private sector for the first time as an investment banker in Chicago. Displaying his standard charm Rumsfeld quickly made friends in high places and began to hear the call of public office. At the age of 30, he ran for an Illinois seat in the U.S. House of Representatives and won. Rumsfeld arrived in Washington D.C. in 1962 and, again, found the right people to know at the right time. He joined Bob Dole, Gerald Ford, and George H.W. Bush as a young up-and-comer and the town quickly knew they had a new generation of leaders waiting in the wings. The four men became very close and those bonds, some now broken, would shape world history for decades to come.

Rumsfeld was a popular congressman and was re-elected in 1964, 1966, and 1968. But he resigned in 1969 to join President Richard Nixon's White House. His role as Director of the Office of Economic Opportunity and Assistant to the President lasted until 1970. By most accounts, Rumsfeld's performance was solid and he impressed President Nixon. In recognition of his contributions, Nixon promoted him to Counselor to the President and Director of the Economic Stabilization Program where he served until mid-1973. He got the chance to try his hand on the international scene next, by serving as the U.S. Ambassador to NATO in Brussels, Belgium, until 1974.

But in August of 1974 the White House was in chaos after the resignation of President Nixon. Rumsfeld, known for his iron-jawed leadership skills and no-nonsense style, was called back to Washington, D.C., to serve as Chairman of the transition to the Presidency of Gerald Ford. His keen sense of secrecy and politics made people uneasy. But most members of the chaotic White House knew he was doing a great job of forcing order during what some would say was a Constitutional crisis. Inevitably, with his presence making such an impact on the daily functions of the White House, Rumsfeld became Chief of Staff of the White House and a member of the President's Cabinet. Before President Ford was voted out of office Rumsfeld was appointed the 13th U.S. Secretary of Defense, the youngest in the country's history at the age of 43. He served in the position from 1975 to 1977.

Many believed Rumsfeld was positioning himself for a run for president. Indeed, most indications were that the young man was trying to pack as much experience as he could in as short a time as possible. He had already worked in very important positions on the domestic and international fronts. Even though he was young, there were very few political foes who could attack him for lack of credentials. The resignation of Nixon had left the GOP in chaos and Rumsfeld started acting like a man with a political mission. He appointed his old friend, George H.W. Bush, to head the CIA. Most insiders considered this a slap in the face for Bush since he was also positioning himself as presidential material. To most politicians, it appeared that Rumsfeld was removing his competition.

But when Ford lost to Jimmy Carter in the election of 1976, Rumsfeld decided against running for president and, in essence, disappeared from Washington. His move into the private sector was astonishing to his fellow politicians, many of whom were glad to see him go. Though he had made a deep impression on Washington, he had made his share of enemies, many in his own party who never got used to his style or his uncanny political talents. These conflicts would arise again when Rumsfeld returned to politics almost 25 years later.

Rumsfeld's sideways move into the private sector was as successful as his political career. His style of speaking has always been very direct and he dashes every point with a folksy style. That same demeanor tends to keep him at arms length from people. Many who know him acknowledge that he is, fundamentally, a mistrusting person. Still, his leadership qualities secured him positions in two Fortune 500 companies in the years that followed his departure from the political scene.

Rumsfeld was not a power-player in Washington anymore but he kept one toe in the water at all times. He worked for the Reagan administration on a number of projects such as senior advisor to the President's Panel on Strategic Systems and special envoy to the Middle East. He also continued to be involved during President Bill Clinton's second term as a member of the U.S. Trade Deficit Review Commission and chaired the U.S. Commission to Assess National Security Space Management and Organization. These are only examples of the dozens of duties he held in the political arena which ranged from chairman of fellowships to board member of Stanford and the National Park Foundation.

But a majority of his efforts went into private industry where he became a wealthy man very quickly. Upon leaving Washington he was offered the positions of chief executive officer, president, and chairman of G.D. Searle & Company, a pharmaceutical company. Over the years, his efforts were recognized as some of the best leadership in the pharmaceutical industry by a number of business organizations. Rumsfeld moved on to serve as CEO of General Instrument Corporation from 1990 to 1993, a leader in broadband technologies. He soon joined the board of another pharmaceutical company, Gilead Sciences, Incorporated, where he focused his efforts until the call came in from Vice-President-elect Dick Cheney in 2000 to join President-elect George W. Bush's staff.

Cheney knew Rumsfeld was qualified to be Secretary of Defense. After all he had done it before as the youngest secretary in history. But Rumsfeld was 68, which meant if he were to take the job he would also become the oldest secretary in history. Cheney and Rumsfeld had stayed close and both agreed on what threats faced the world. For instance, both had lobbied President Clinton hard to consider Iraq an immediate danger to United States security. After some consideration, Rumsfeld accepted the Bush administration's offer.

Upon taking the oath of office, Rumsfeld, in his traditional fashion, announced that things were going to change. He had been a Washington insider for decades and had strong opinions about how things worked. He felt he knew what needed fixing and he set out to fix it. The only problem was that many of the enemies he had left behind when he went into the private sector were still in Washington-and they still did not like him one bit.

First, he wanted to cut defense expenditures on old weapons and move the focus to new ones that could better deal with the threats we face in the modern world. This was controversial since many in the military believed this challenged their roles as overseers. But to make matters even more tense, Rumsfeld wanted to take another look at the way the military was organized. He wanted to reshuffle United States troops in a way that could allow the country to go to war quickly, anywhere in the world. His tactics were not appreciated by people who were in a system they had lived with their entire professional careers. For any Secretary of Defense to make sweeping changes it is incumbent on them to inform congress. But many in the legislative side were complaining about being left out of the loop. Most people in Washington believed Rumsfeld was going to shoot himself in the foot with his approach to reshuffling his department and redefining its responsibilities. He had the energy to change the world but he did not necessarily have the power. Most political pros thought Rumsfeld would be out of the White House within a year.

But then disaster struck, exactly the kind of disaster for which the office of the Secretary of Defense is designed. While Rumsfeld's experience was indisputable, no one could be prepared for September 11, 2001. The morning of the attack Rumsfeld was in his office at the Pentagon. He felt the building shake and went outside to find chaos. Without knowing what had happened he helped carry some people clear of danger and was then led to the War Room where he was updated on the events of the morning. Since he is responsible for directing the defense of the United States, the world looked to him for a tactical response. When it became clear that Osama Bin Laden was behind the attacks, Afghanistan became the prime target for America's wrath. Interestingly, only hours after the 9/11 attacks, Rumsfeld was working to also put Iraq in the crosshairs. A CBS News report in September of 2002 revealed notes taken during the hours after the attacks. "Go massive," the notes read. "Sweep it all up. Things related and not. Judge whether good enough hit S.H. (Saddam Hussein) at same time. Not only UBL (Osama Bin Laden)." Once President Bush declared the attacks as acts of war, Rumsfeld was, essentially, given the go-ahead to arrange for America's defense as he saw fit.

Being the efficient type, Rumsfeld took advantage of the times to push through the changes he had worked hard to make. The result was a new plan called the Unified Command Plan, which sought to make the rules of sizing our forces more streamlined and relevant to the threats the United States now faced. The reshuffling and top-down analysis of our military led to many more controversies, not least of which was the reinstatement of the "Star Wars" program, otherwise known as the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI). The program was introduced during the Reagan administration and promised to create an impenetrable shield of missile defense around the country with a series of satellites and powerful lasers that could knock down any attack from the air. SDI's confinement to the laboratory (i.e. no real world testing) was an integral part of the ABM treaty signed by the United States and the former Soviet Union. By giving SDI new life, many feared a new arms race could ignite between the two countries. Rumsfeld brushed off this kind of thinking. "No U.S. president can responsibly say that his defense policy is calculated and designed to leave the American people undefended against threats that are known to exist," Rumsfeld was reported to say in an Associated Press piece in the New York Times . "[Missile defense] is not so much a technical question as a matter of a president's constitutional responsibility."

Rumsfeld's power and influence in the Bush White House only increased when the war in Afghanistan ended after only a few days. With a new mandate to defend the country from weapons of mass destruction, Rumsfeld and Cheney moved to make Iraq the next target. Saddam Hussein had developed a large cache of biological weapons before the first Gulf War. Once he lost that war he was ordered by the international community to destroy all weapons of mass destruction. The United Nations was sent in to monitor their compliance. But in 1997, the inspectors were kicked out and many, Rumsfeld included, believed he was building a new arsenal. He thought if Hussein could use those weapons against the United States, he would. Which led Rumsfeld to conclude that Hussein must be removed from power. With backing from many people in the Bush administration, the path to war was laid and Rumsfeld was one of the leaders.

Once again, his gruff attitude got him in trouble. As many in the international community, including France and Germany, scoffed at the idea of preemptive war, a frustrated Rumsfeld tagged them "Old Europe." But that was the least of his problems. In his own administration he was meeting resistance with the Secretary of State, Colin Powell. Powell wanted to let the newly deployed United Nations inspectors do their work in Iraq. The media had a field day playing up the conflict and, in the end, Bush sided with Rumsfeld.

Rumsfeld did not just tell his people to get to work, he got involved. Proposal No. 177 is a series of documents that conveys, in detail, the plans of deployment and how to get what infantry where and by what date with all the weapons, people, and supplies it needs. These are the kinds of documents that are usually handed off to the underlings. But Rumsfeld read every word, challenged ideas that seemed rooted in old thinking and used his authority to make the attack on Iraq a new chapter in military deployment.

When the war began on the ground on March 20, 2003, many politicians watched closely to see how Rumsfeld's influence would carry onto the battlefield. Many came out against him in the press, especially retired officers, when the advance on Baghdad slowed down. But, in the end, the Iraqi army was defeated and American troops took control of the capitol. Rumsfeld basked in the praise many gave him for the lightning-fast victory. To his supporters, the war was vindication for Rumsfeld and proved that he had been right about reorganizing the armed forces. But in the months after the defeat of the Iraqi Republican Guard, the battle became more like a guerilla war. American soldiers were asked to police the country, but various factions, both Iraqi and not, sabotaged the infrastructure and made it difficult to keep the peace. Rumsfeld's vision of armed forces that can do a little bit of everything, and do it fast and well, will go through many evaluations over the years as the United States tries to secure the peace in Iraq. However history judges him and his efforts, his name will always be tied to world history after 9/11.

To help quell the guerilla attacks, more American troops were sent to Iraq. On December 4, 2003, Rumsfeld visited Afghanistan, where he urged Afghan warlords to surrender heavy weapons, discussed plans for stopping a lingering insurgency, and pressed for economic development. The next day, he became the first senior administration official to visit the country of Georgia since a peaceful, popular revolt forced out the government of Eduard A. Shevardnadze. Rumsfeld expressed strong support for Georgia's territorial integrity in the face of rising secessionist sentiment and the presence of Russian troops on its territory. On December 13, 2004, Iraqi President Saddam Hussein was captured by American forces, who found him hiding in a hole beneath a two-room shack on a sheep farm near the Tigris River. His capture boosted United States claims that the situation in Iraq was under control.

In front of some of Europe's fiercest critics of the United States-led war in Iraq, Rumsfeld offered an impassioned defense of the conflict. He placed the blame for the war on former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein for his "deception and defiance," as well as his refusal to abandon his illegal weapons program. When it came to light that Iraqi prisoners of war had been abused by American military personnel, Rumsfeld said he would take "all measures necessary" to ensure that the abuse of detainees a Pentagon report alleged took place at a prison in Iraq "does not happen again." President Bush defended Rumsfeld against U.S. politicians and foreign leaders who demanded the secretary's resignation. On May 13, 2004, Rumsfeld visited Abu Ghraib prison in Baghdad, Iraq, the site of Iraqi-prisoner abuse. While there, he gave a rousing speech to hundreds of troops and military police, indicating that those who committed prisoner abuse would be dealt with fairly.