Devo biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Akron, Ohio,U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2012-04-26

Credited as : New Wave band, futuristic-look, Gerald Casale

0 votes so far

Akron, Ohio, natives and Devo founders Mark Mothersbaugh and Gerald Casale met as art students at Kent State University around the time of the infamous riots during which four students were killed by the National Guard; Casale called it "the most devo day of my life." The two were interested in an audio-visual project, with Casale on bass and Mothersbaugh playing progressive-sounding keyboard music and providing vocals. With their brothers, Bob Casale and Bob Mothersbaugh, on guitar, and Alan Meyers on drums, Devo formed, performing for audiences in Ohio, then branching out to New York and Los Angeles.

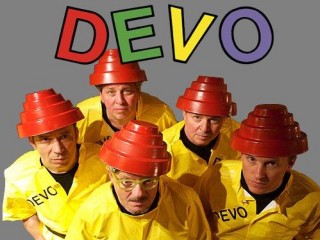

During live shows, Devo bandmembers dressed identically, often in strange, futuristic-looking garb that included flight suits, plastic toupees, or red tiered headwear resembling inverted flowerpots. Devo's act involved energetic stage antics, images projected on a screen behind the band, and the display of short films and videos. Eventually playing to capacit crowds and making television appearances on shows like Saturday Night Live, the band would also begin getting attention from such rock luminaries as Iggy Pop, David Bowie, and Brian Eno.

Devo satirized their views on dehumanization due to industry and technology with their first single, released on their own label, Booji Boy Records. The song, "Jocko Homo," succinctly asserted, "They tell us that/ We lost our tails/ Evolving up/ From little snails/ I say it's all/ Just wind in sails/ Are we not men?/ WE ARE DEVO!/ We're pinheads now/ We are not whole/ We're pinheads all/ Jocko Homo." The tune was a hit in the underground music scene and led to a contract with Warner Bros. in 1978; their first album would be produced by art-rock innovator Brian Eno. A People magazine reviewer wrote in 1980, "Devo's debut album (Q: Are We Not Men? A: We Are Devo!) no longer seems preposterous. It was obviously seminal."

Almost ever since, critics have debated whether or not Devo's later work continued the politics on their debut project or sold out to the conditions they were satirizing. Simon Reynolds of Melody Maker remembered Devo's music from the 1970s as "a deliberately opaque vision of mass braindeath, in which rock'n'roll, shorn of its rebellious pretensions, would be a prime agent of behaviorist control." With nothing less than pure appreciation, he added, "Disinfecting rock of its dirt, streamlining its all-too-human edges, Devo created perhaps the most repellent rock in history."

Unfortunately, however, Reynolds implied that very innovation is exactly what made the band too quickly dated. Kenneth Korman of Video generously suggested that "the larger story ... involves the complex relations among art, commerce and popular culture.... Devo never sold out its original intent--principally to make people stop and think--but eventually sagged under the weight of industry pressures."

Whether or not they "sold out," Devo did experience commercial popularity. Their first album included a clipped-sounding cover version of the Rolling Stones' "(I Can't Get No) Satisfaction," which became a hit, and Freedom of Choice, their third album, went gold and contained their hallmark single "Whip It." They also received attention for the 1981 remake of Lee Dorsey's "Working in a Coal Mine," which was included on the soundtrack for the animated film Heavy Metal.

Devo's poor man's art struck a nerve in the early eighties despite what Melody Maker's Horkins described as an unlikely environment: "Such implorable collisions of art, intellect, insanity and musical experimentation seemed inconceivable, let alone functional, within a corporation so geared up to supplying the world with endless hoards of spandex clad axe heroes and Michael Jackson videos."

But it was precisely the audience alienated by pop music that swarmed to Devo's unconventional side. They were the perfect outcast's band, ignored at best or booed at worst by their hometown audiences who saw them as the high school nerds and awkward rebels they were. They made little effort to combat these perceptions, willing as they were to be "decked out like some Fifties B-movie white supremacist futurists and ... prone to choreographed bouts of spasmodic leaping about," according to Melody Maker's Horkins.

Devo's career declined throughout the 1980s, however. True to their analytic spirits, the band seemed to have been cognizant of the shifts both in the world around them and in their music. With genuine sympathy, Melody Maker's Tony Reed reported of 1988's Ttal Devo, "There is a great sadness here, reflected in the titles and the lyrics, and it's the terrifying sense that Devo themselves might know just what an irrelevant anachronism their techno-pop angst strategy has become."

Some critics have come to terms with Devo by labeling them hippies, even folk singers. A Stereo Review critic called their 1990 release Smooth Noodle Maps "an electrified folk album," and deemed the group "disillusioned idealists whose outlook is more hippie than yuppie." That writer took them quite seriously, however. He concluded that "Devo is and isn't being funny this time. On the precipice of a new age, the band is back from the computerized drawing board with new ideas, banking on a calculated combination of emotion, intellect, wit, and rhythm to point us foolish humans over the hump toward a better future."

Other critics have been less inclined to give Devo the benefit of the doubt: "Depeche Mode for toddlers," reporter Zane termed the group in Melody Maker. The release of Total Devo, Scott Harrah wrote for People, "will make listeners wish that Devo had stayed in its pop-cultural purgatory." Michael Azzerad in Rolling Stone aspired for sympathy but ended with contempt. "Maybe the members of Devo are mocking the system that built them up and then knocked them down," he wondered of Total Devo, but concluded, "No.... Actually, they're making the kind of vapid music they used to ridicule in countless songs and interviews.... If you listen closely, the bass drum on this record sounds suspiciously like a digital sampling of the sound of a dead horse being beaten."

Azzerad's criticism was particularly painful given that Devo initially achieved fame not only with their ironic lyrics but through their progressive electronic music. "[We] were pioneers in the use of electronics," synthesizer player/singer Mark Mothersbaugh asserted. Their music is really part of a complicated system of noise. Back in the early 1970s, Mothersbaugh elaborated for Melody Maker's Tony Horkins, "I used to take records with a drum solo or something, or just one bass line I liked, and just mutilate the record so that it stuck and skipped back to give you a loop of that one bit. [We'd] use things like windscreen wipers or washing machines as backing tracks." As they progressed, they "went through the whole history of the evolution of sequencers."

To some extent, electronics were an accident of fate for Devo. Mothersbaugh theorized that "perhaps if we had been rich kids, rather than poor factory kids, we would have made a feature film or put on a theatrical play, you know? But what we could afford was guitars and drums and some cheap electronic home built synthesizers and music happened first." Devo's attitude toward their medium, however, was anything but casual. Mothersbaugh claimed that Devo was distinguished from other musicians at the time who "were coming to electronics as keyboards first and approaching them as glorified pianos and organs.... [We] were kind of heading from the opposite direction, coming from electronics first and the keyboard was something for your fist to pound on."

Apparently shameless, Devo was still very dismayed when they felt misunderstood. In response to various mean-spirited critiques of the group's work, Jerry Casale remarked to Rolling Stone's Goldberg, "Well, obviously, we're Nazis and clowns. They're all right, all those people.... We're assholes. Everything they accuse us of is true. We're subhuman idiots." Casale's bruised ego reveals what the band considers fundamentally true about themselves: that they care, that they want to teach. Their goal is to communicate the message using "information instead of emotions to make decisions. A lot of people make decisions based on paranoia, hatred, selfishness and love." Devo is of the philosophy that it is critics' fear of their difference that makes them reject their music: "[We] threaten them."

Though much of Devo's material was repackaged and reissued in the early 1990s, the band was on hiatus. During this time, Gerald Casale became involved in directing music videos, and Mark Mothersbaugh kept busy in a range of areas. He pursued his interest in fine arts by producing and showing silk screens, wrote a lengthy tome titled What I Know, and composed music for the opening and closing credit sequences of television programs, including Pee-Wee's Playhouse and Liquid Television.