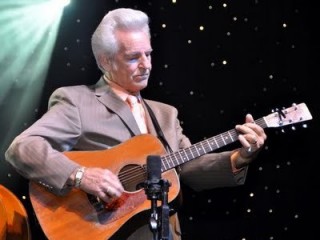

Del McCoury biography

Date of birth : 1939-02-01

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Bakersville, North Carolina,U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2011-12-13

Credited as : bluegrass musician, leader of the Del McCoury Band, received a National Heritage Fellowship

4 votes so far

From out of the revolving ranks of the now-legendary Blue Grass Boys--the crack band backing bluegrass music founder Bill Monroe--have come a legion of talented musicians: Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, Jimmy Martin, Sonny Osborne, Vassar Clements, and, in 1964, a young musician named Del McCoury. From his start as guitarist and lead singer for Monroe during the early 1960s, McCoury has gone on to make his mark on modern bluegrass as one of the most popular performers of the now-classic "Monroe" sound that first set fire to audiences during the 1940s. Nashville promoter Lance Leroy once commented, "As a bluegrass purist, you could get papers on Del McCoury," and not many would disagree. With an engaging confidence, a distinctive tenor that essentially defines the "high lonesome" sound, and an unflaggingly energetic approach to his music, it is no wonder that McCoury and his talented band are considered "bluegrasser's bluegrassers," respected by their musical peers and performing at the peak of their profession.

Delano Floyd McCoury was born on February 1, 1939, in Bakersfield, North Carolina. When young McCoury was two, he moved with his parents, two brothers, and three sisters to York County, Pennsylvania, where he was raised around "old-time music"--music from rural Kentucky and Tennessee. When his older brother brought home a 78 rpm record by a hot new country act called Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, young Del finally sat up and listened. "As a kid I liked music," he recalled in an interview with Contemporary Musicians (CM). "I can remember singing when I was just little. But when G.C. [Grover Cleveland McCoury, Del's older brother] bought that record--it was Earl Scruggs--when I heard him pick I thought, 'This is really something.' And I just couldn't get that out of my head." McCoury was soon devoting most of his free time to learning Scruggs's banjo licks.

After graduating from high school in 1956, McCoury joined the Blue Ridge Ramblers as a banjoist. From there he moved to Baltimore, Maryland, and picked with Jack Cooke, a former bass player with the Blue Grass Boys. The job playing alongside Cooke would provide young McCoury with the opportunity to earn his Ph.D. in bluegrass. When Monroe stopped at Cooke's Baltimore bluegrass club on the way up to perform in New York state in 1963, he was in need of a banjo player. Impressed with the then-22-year- old McCoury, Monroe offered the young banjoist a full-time spot with the Bluegrass Boys.

McCoury took some time making up his mind to move south; meanwhile Monroe had lined up banjo player Bill Keith. "Monroe needed a lead singer in the worst way," McCoury recounted for CM. "More than anything, he depended on them pretty heavy. And he asked me. I said, 'Man, I don't know if I could do that or not,' you know. But I auditioned on his guitar, singin' lead for him. I didn't know all of his songs--I knew choruses but I didn't know all the verses. I sang what I did know, and played the guitar. And he said, 'Well, I tell you what. I'll try you for two weeks. If it sounds pretty good, I'll get you in the union here.' I thought, 'Well, I don't know if this is gonna work out.' I wasn't sure if I wanted to do it anyway, you know. But I kinda liked it and after about two weeks, they took me down to the union hall and signed me up."

McCoury played with Monroe for a year, recording one LP with the band. While he loved touring and got along well with the sometimes taciturn Monroe, being lead singer for a prolific songwriter like Monroe was no simple task. "My hardest problem was learning those words," McCoury explained to CM. "All of those words, all at one time. I had sung since I was a little kid and sung every part. But all those lyrics--now that was a different story. It was hard to jam all those songs in your head at one time. Lots of times I would sing wrong words, but I never would stop; I would keep it going somehow."

McCoury continued in his CM interview, "Monroe made a new record while I was with him. And that kinda helped me because I knew he wanted to do these new songs. So I learned all those songs off that one album. But then I still had to do old things because Bill, he just don't say 'Now, okay, today we're gonna do this song, or that song.' He just gets on stage and does what he wants. And if somebody requests something that he recorded 20 years ago, he'll do it. And," McCoury laughed, "you gotta know it."

After he left Monroe in 1964, McCoury, along with his new wife, Jean, moved from Tennessee to Los Angeles, where he and fiddler Billy Baker played with the Golden State Boys. The couple would return to their familiar Pennsylvania after less than a year, and by 1967 Del had formed the Dixie Pals, drawing fine instrumentalists from the area to begin building the blues-based, soulful sound for which he would become known. The group's first album, High on a Mountain, recorded for Rounder in 1972, firmly established them as a top act on the bluegrass festival circuit.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, McCoury and the Dixie Pals stuck to the traditional bluegrass style popularized by Monroe, but with a difference. "You know, what excited me back when I first heard [bluegrass] was the way that it was done," McCoury told CM. "The way that five-piece band was, the sound they got. And it still does. It excites me to listen to the old stuff that I first heard. And so through the years I didn't want to change the structure of that band. I wanted to keep that same sound. When I went out on my own, I knew that I had to get different songs, and write songs, because I couldn't play shows with other bluegrass artists and do their songs like I had done Bill Monroe's and Flatt & Scruggs's before that. I imagine my taste for songs is a little different than somebody else's. And I think that's how you develop a sound, you know, with the songs you record." In addition to reworking songs by others, McCoury includes several self-penned numbers on each of his albums. "This Kind of Life" and "Dreams" are two of his most popular tunes; his "Rain Please Go Away" has become a bluegrass standard.

In 1981 McCoury's elder son, Ronnie, joined the band as mandolinist and was followed in 1987 by his younger brother, Robbie, who was then still in high school. Eventually considered two of the most talented instrumentalists within the bluegrass community, Ronnie and Robbie were both inspired at an early age to follow their father's lead. "We're as proud of dad as he is of us," award-winning mandolinist Ronnie told Brett F. Devan in Bluegrass Unlimited. "I guess he was my best inspiration in learning the mandolin."

As the decade of the 1980s neared a close, McCoury was fast approaching the musical chemistry that would make his popularity skyrocket in 1989. Now flanked onstage by his sons, he began focusing on the blues and country influences that caught his ear. In 1987 the band decided that a name change was in order; by 1990 they would have achieved widespread national prominence as the Del McCoury Band. Since then their momentum has been unstoppable. In 1992 bassist Mike Bub and fiddler Jason Carter added their strong instrumental and vocal talents to round out the band's timeless bluegrass sound.

Led by McCoury's bluesy, high-pitched tenor voice and rhythmic guitar, the talented group has followed both the letter and the law of the original Blue Grass Boys lineup- -the sound born of Monroe's mandolin, Scruggs's banjo, Lester Flatt's guitar, Chubby Wise's fiddle, and the bass playing of comedian Cedric Rainwater. "This remains the bedrock sound of the music," noted Devan in Bluegrass Unlimited in 1990, "almost 45 years after the now legendary coalition finalized its form and first introduced it to millions of ... Grand Ole Opry listeners. The McCourys and their compatriots are now reminding us of how good it really was."

McCoury's voice is the trademark of the Del McCoury Band; it is "what fans love--and detractors hate--about bluegrass," as Jim Patterson put it in the Tennessean. "[McCoury] sings it high and lonesome, and is as legendary a vocalist in bluegrass as George Jones is in country music." McCoury is also one of those rare musicians who has allowed his style to mature as he has. "It's funny about singing," he told CM. "I can do more with a song now than I could before. And I think it's because I have these young musicians backing me up. My sons got on stage with me, and all of a sudden the other guys in the band are [my sons'] age. And that helps keep the spark up. And then I can sing better. It keeps me from gettin' older too."

Within McCoury's broad-ranging tenor vocals resonate the mournful wail of wasted lives, love lost, and the raw hurt of living. But the effect is far from depressing; a subtle humor is never far away. "McCoury's vocals are the icing that makes the cake," commented Jim Ridley, reviewing the musician's 1993 release, A Deeper Shade of Blue, in New Country. "Whether he's cackling Lefty Frizzell's 'If You've Got the Money Honey' in randy high spirits or romping through Willie Nelson's 'Man with the Blues,' [McCoury] infuses every tune with joyous vitality, no matter how sad the song. Where Jerry Lee Lewis wailed 'What Made Milwaukee Famous' with a drawl that said 'go to hell,' McCoury sings it as though he's thankful to Heaven to still be making noise."

While his role in modern bluegrass has been to carry the Monroe traditions forward into the next century, McCoury looks forward to the continued evolution of the music. "It's bound to change some," he noted of the bluegrass sound. "I know the stuff that I first heard was really excitin' to me. But maybe to somebody else it wouldn't be, like younger people. But that first band, that Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, Rainwater, and Chubby Wise [group]: it's still good music. That music will probably stand forever." With his traditional appeal, McCoury has received numerous awards from the International Bluegrass Music Association (IBMA); "I always thought I could sing a little," he deadpanned to the audience of the 1994 IBMA Awards Show, during which he was voted entertainer of the year by the professional bluegrass community. "But I didn't know I could entertain people. I can't dance. Bill Monroe can dance."