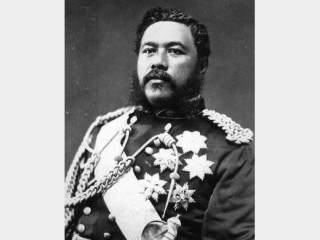

David Kalakaua biography

Date of birth : 1836-11-16

Date of death : 1891-01-20

Birthplace : Honolulu, Oahu

Nationality : Hawaiian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-02-14

Credited as : King of Hawaii, Hawaii for Hawaiians,

David Kalakaua was a Hawaiian King who was a staunch supporter of native Hawaiian civil rights. His opposition to the white business community led to a rebellion forcing him to sign a new constitution relinqushing his powers as head of state.

David Kalakaua ruled Hawaii as its king from 1874 to 1891, a period of significant change in the land's internal political makeup and its relationship with the United States. A supporter of the rights of the native peoples of the Hawaiian islands, the monarch frequently clashed with the powerful haole (a term used for people who are not natives of Hawaii) business community during his reign. The animosity between the two camps, which was exacerbated by Kalakaua's sometimes questionable use of his power, resulted in a white-led rebellion in 1887. A few days later, Kalakaua was forced to sign a new constitution that stripped him of his power, relegating him to figurehead status.

Kalakaua made his first bid for Hawaii's throne in 1873. The Hawaiian legislature, comprised largely of native Hawaiians and haoles qualified by wealth or land-ownership to be either electors or elected representatives in the legislature, was presented with two choices: Kalakaua, who ran on a campaign slogan of "Hawaii for Hawaiians," a sentiment that did not endear him to the islands' white power brokers, and William C. Lunalilo. Lunalilo won easily, but he died a year later, leaving no successor. Another election was held to determine Hawaii's monarch. Buoyed by the support of the influential Walter Murray Gibson, Kalakaua was victorious in the 1874 election.

The triumphant Kalakaua toured the islands, stopping in every district to affirm his primary goals. "To the planters, he affirmed that his primary goal was the advance of commerce and agriculture, and that he was about to go in person to the United States to push for a reciprocity treaty. To his own people, he promised renewal of Hawaiian culture and the restoration of their franchise," wrote Ruth M. Tabrah in Hawaii: A Bicentennial History. The proposed reciprocity treaty with America was important for both sides. Hawaii knew that a trade agreement with the giant United States would significantly boost its domestic economy. America, meanwhile, wanted to prevent Hawaii from developing close commercial or political ties to any other nations (such as Britain). Ralph Kuykendall reported in The Hawaiian Kingdom that American minister to Hawaii Henry Peirce successfully argued that a treaty with Kalakaua's kingdom would hold the islands "with hooks of steel in the interests of the United States, and … result finally in their annexation to the United States."

Consummation of the 1875 treaty helped Kalakaua's popularity in Hawaii in some respects, but the king lost the support of the white business community for various reasons. Many of his ministerial appointments, for instance, went to native Hawaiians, a reflection of the king's consistent loyalty to his core constituency. They also loathed Gibson, Kalakaua's premier, whom they viewed as a traitor. Kalakaua's white opposition grew increasingly frustrated with their lack of power, and their rhetoric grew increasingly bigoted in tone as their anger grew. "Attempts to build a strong political party of opposition ran into the dismal fact that Kalakaua and Gibson controlled too many votes," wrote Gavan Daws in Shoal of Time: A History of the Hawaiian Islands. "In 1880 a slate of Independents was drawn up, but after six years Reform had not got very far. The king still dominated the legislature."

During the 1880s other events further alarmed the haoles. Kalakaua's decision to throw an expensive coronation ceremony in 1883 (nine years after first ascending to the throne) angered many, and they disagreed with the government's tentative steps toward universal suffrage, but of greater consequence was his decision to welcome increasing numbers of foreigners (especially Chinese and Japanese people) to the islands. In 1883 a government representative delivered a speech in Tokyo in which he declared that "His Majesty Kalakaua believes that the Japanese and Hawaiian spring from one cognate race and this enhances his love for you," reported Kuykendall. "Hawaii holds out her loving hand and heart to Japan and desires that your people may come and cast in their lots with ours and repeople our Island Home with a race which may blend with ours and produce a new and vigorous nation." Thousands of Japanese families accepted Kalakaua's offer, to the chagrin of white landowners and businessmen who feared further loss of influence.

Early in 1887, a haole-dominated organization called the Hawaiian League formed in opposition to Kalakaua and Gibson. Shortly after its formation, "a splendid scandal, just what the League wanted, burst about the head of the king," remarked Daws. Kalakaua had accepted a big payment from a Chinese businessman to secure a government license for opium imports, only to award the license to another Chinese businessman without returning the money to the first individual. News of this scandal gave the League the excuse it needed to move. They detained Gibson, and armed members of the League patrolled Honolulu's streets. Kalakaua knew that his largely ceremonial royal forces were outmatched, so he called on the governments of Britain, America, and other nations for aid. Instead, "they urged him to yield to the demands of the league in order to preserve the peace of his kingdom," said Tabrah. "On July 6, he signed the constitution that relegated him to a figurehead and that imposed a fairly high property ownership qualification on those running for the new legislature." This new constitution, which came to be known as the Bayonet Constitution, marked the end of Hawaii's kingdom.

The Hawaiian League proceeded to dismantle many of Kalakaua's programs. Two years later, Kalakaua retired to Waikiki, his health failing. He made a final visit to the United States, where he was given a warm welcome. "A title was a title, and (the Americans) enjoyed him as a personality," said Tabrah. "He died there in San Francisco after a final whirl of being adulated, feted, and given the fond aloha of American friends."