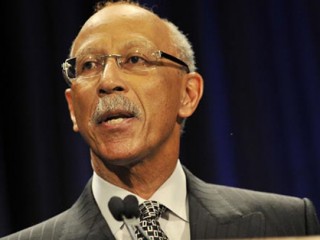

Dave Bing biography

Date of birth : 1943-11-24

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Washington D.C., U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-04

Credited as : Basketball former player NBA, played for Detroit Pistons 1966-75, businessman and current mayor of Detroit

2 votes so far

His #21 was retired by the Detroit Pistons, and in 1996 he was named as one of the NBA's 50 Greatest Players of all time.

He was elected mayor of Detroit in a special election on May 5, 2009 and was sworn in on May 11, 2009. Bing won the full-term mayoral election on November 3, 2009, defeating challenger Tom Barrow.

When Dave Bing was elected Mayor of Detroit, no one who knew him was surprised. The calm, measured determination that had defined him on the basketball court had made him a millionaire many times over in the steel industry. Leading a city out of a political and financial mess seemed like a logical next step.

During his 12-year NBA career, Dave had the ability and all-around game to score 35 a night, but he instinctively knew that this would do his teams more harm than good. Although he rarely shied away from an open shot, he always looked for an open teammate first. Year after year, he led his team in both scoring and assists—and playing stellar defense. Dave had a knack for keeping mediocre clubs competitive and making sure that everyone got to contribute, regardless of the outcome of a game. Sounds like he's the right man for the job in the struggling Motor City.

David Bing was born on November 24, 1943 in Washington, D.C. When Dave was five, he tried to build his own play horse by nailing two pieces of wood together. While “riding” it down the street, he tripped and the nail stuck into his left eye. Surgeons were able to repair the damage, but they told the Bings that their son might lose his sight. Dave regained his vision, but it was always blurry after that.

Basketball was a big deal in Dave’s neighborhood. Elgin Baylor was the local playground legend. When he gained national prominence as a collegiate superstar for Seattle in the 1950s, many young athletes began to see it as a way out of the ghetto. Dave had an excellent all-around game, but was small for his age, so he focused for many years on baseball.

Like most of their neighbors, the Bings labored hard to make ends meet. Dave’s father Hasker was a bricklayer who suffered a serious head injury on the job. His mother worked as a housekeeper. Neither brought home enough for the family to live on by themselves, and there were times when only one had steady work. For most of his childhood, Dave and his three siblings shared two beds.

Despite the family’s meager homelife, Dave’s father did make invaluable contributions to his teenage son. When Dave was 14, he joined his father on a worksite. Hasker asked Dave to build a wall. When it was done, his father leaned against it and it collapsed. The lesson was clear—a job isn’t done until it is well done. More important, Dave learned the value of a solid foundation, something that would help him both on and off the court.

When Dave enrolled at Spingarn High School in 1958, he met basketball coach William Roundtree, who became like a second father to him. Dave quickly established himself as one of the stars of the varsity basketball and baseball teams. Spingarm’s hoops squad was an offensive powerhouse, so Dave’s driving and jumpshooting fit nicely into the coach's high-scoring system. During the 1961–62 season, Dave was one of seven players to average in double figures. That spring, a scheduling conflict forced him to choose between a basketball tournament and a baseball tournament. Dave settled on basketball and was named tournament MVP.

Dave Bing, 1980s TCMA

Of course by this time, several colleges were following his progress. He was a rock-solid 6–3 and 185 pounds as a high school senior. UCLA, Michigan and Syracuse were his most ardent suitors. Star tailback Ernie Davis did a big sell job on the Orangemen, and Dave decided to take the school’s scholarship. Despite being voted All-Metro and All-East, Dave was still unsure of his talent and did not want to risk humiliation in a major hoops program.

The Orangemen were a football powerhouse, but a basketball laughingstock. The year before Dave arrived, the upperclassmen had run a losing streak to a mind-boggling 27 games. Dave changed that culture of losing in 1963–64, his first varsity season for Syracuse. He broke the school’s sophomore scoring record with 556 points and led the team to a 17–8 record. The boosters were ecstatic when the Orangemen earned an NIT bid. Even though they lost to NYU in the opening round, the season was an unqualified success.

By this time, Dave was a married man. He wed his high school sweetheart Yvette at the age of 19 and had two daughters by the time he graduated.

Dave was in college on a full ride, but he worked as a janitor to earn a regular paycheck for his family. During the summers, he held basketball clinics for kids to make extra money. He was such a fine fundamental player that he had no trouble teaching kids the basics of basketball. Later, as a pro, he had his own summer camp in the Poconos.

As a junior, Dave upped his scoring average to 23.2 points per game and was named a First-Team All-American by The Sporting News. The following year, he was a consensus All-America—the first one for Syracuse basketball in nearly four decades. By the end of his senior season, Dave had obliterated the school’s career scoring mark by more than 400 points, posting 1,883 points in three seasons. His 28.4 average (fifth in the nation) and 794 points as a senior set new records as well. Dave led the Orangemen to a 22–6 record and the NCAA Tournament. They reached the East Regional Finals, where they lost to Duke.

The New York Knicks and Detroit Pistons held the first two choices in the 1966 NBA draft. The Knicks had won the right to make the first selection after winning a coin flip. The Pistons had already gone on record that they would have take Michigan’s Cazzie Russell with the first pick. New York trumped them by picking Russell, who would have been Dave’s teammate had he played for the Wolverines. Detroit “settled” for Dave. He joined a club that was coached by forward Dave DeBusschere, who was a solid rebounder and scorer. DeBusschere was joined on the front line by center Ray Scott.

Dave’s first NBA game was a disaster. Coming off the bench, he missed every shot he took. When the final buzzer sounded, he pondered the first scoreless game of his life. His play improved over the next couple of weeks. DeBusschere gave Dave a start, and he responded by hitting his first eight field goal attempts. The following game he netted 35. In a game against the Boston Celtics, Bill Russell assigned his best defender, K.C. Jones, to shadow Dave when he came into the game. Jones shut him down, but afterwards said he knew the kid would be a star. Instead of standing around the perimeter like most rookies, Dave looked for other ways to help the team on offense and wore Jones out. In the second half, Dave got his shots and ended up scoring in double figures.

In late November, the Pistons shocked the NBA by surging into first place with a four-game winning streak. They made it there by defeating the Lakers 124–121. Clinging to a one-point lead and with Los Angeles primed to beat them at the buzzer, Dave lost his man and soared above the rim to tap in a teammate’s miss to give his club a three-point bulge. In their next meeting, Dave torched the Lakers for 28.

Dave eventually won a starting job in the backcourt next to Eddie Miles, aka the Golden Arm. Tom Van Arsdale, the starter at the beginning of the year, became Detroit’s sixth man, playing both guard and forward. Ron Reed—like DeBusschere a moonlighting baseball pitcher—backed up John Tresvant at power forward.

Ernie Davis, Heisman card

The Pistons had not enjoyed a winning season since 1955–56, and Dave’s rookie year was no exception. They lost 51 games, and in the final month DeBusschere was relieved to be relieved of his coaching duties. Things took a turn for the worst after Scott was dealt to the Washington Bullets at midseason. His replacement, center Joe Strawder, was a hacker of the first order and managed to lead the NBA in personal fouls and disqualifications despite averaging just 27 minutes per game.

No one had any complaints about Dave. To the contrary, he was a revelation. He led the team with 20.0 points ands 4.1 assists per game. Then as now, the backcourt was generally divided into two roles, point guard and shooting guard. Dave did well enough to function effectively in both spots. He had good moves, size and explosive quickness—a recipe for success at any position. Indeed, Dave would rank among the league’s top scorers and assist men for several years. Only DeBusschere logged more court time than Dave, and only Miles appeared in more games. Dave was named NBA Rookie of the Year ahead of talented first-year stars such as Cazzie Russell, Lou Hudson, Archie Clark, Jack Marin, Walt Wesley and Clyde Lee.

The Pistons took a major step forward in 1967–68, posting 40 wins—their best mark since the mid 1950s. The club was now in the East, to accommodate expansion teams in Seattle and San Diego. Jimmy Walker joined the team out of Providence, and Terry Dischinger returned from two years in the military to give Detroit a solid rotation. DeBusschere and Miles had a good years, taking some of the heat off Dave, who upped his scoring average to 27.1. He led the NBA with 2,142 points, but finished behind Oscar Robertson in the scoring race. The Big O, who lost a month to injury, finished at 29.2. The last time a guard had led the NBA in points was in 1946–47, when Max Zaslofsky turned the trick.

A late-season trade with the Cincinnati Royals netted Happy Hairston, Jim Fox and Len Chappell—all of whom helped the Pistons beef up their rebounding. More important, they enabled Detroit to finish one game ahead of Cincinnati, thus securing the fourth and final playoff berth in the division. In the first round, the Pistons put a scare into the Boston Celtics, splitting the first two games and then taking Game 3 at the Boston Garden. The Celtics came to their senses and swept the final three games on the way to the NBA crown. Dave’s 28.2 scoring average in six games was third-best in the postseason behind Jerry West and Elgin Baylor of the Lakers.

After the season, Dave was honored as a member of the All-NBA First Team. He supplanted West on the squad, joining Robertson, Baylor, Wilt Chamberlain and Rick Barry. Dave would make the All-NBA First Team again in 1970–71.

Instead of continuing their climb to respectability, the Pistons faltered in 1968–69. Their front line simply could not compete, and they kept the fledgling Milwaukee Bucks company in the Eastern Division cellar much of the year. The Pistons fired coach Donnie Butcher after 22 games and replaced him with Paul Seymour. The losing continued.

Early in the season the team made a blockbuster trade, sending DeBusschere to the Knicks for Walt Bellamy, a legitimate center, and guard Howie Komives. Bellamy and Hairston pulled down about 25 rebounds a game. Dave scored 23.4 per game, working beside Miles, Walker, and later Komives. None of these players was much in the playmaking department, so Dave actually saw his assists rise, often registering a double-double.

When the season ended, Dave started hearing overtures from the ABA. The Oakland Oaks had moved across country to Washington and were having trouble convincing Rick Barry to come with them. Owner Earl Foreman needed a big name to draw fans. Signing a local kid like Dave was like money in the bank. Dave’s first NBA contract had paid him $15,000 a year, and although the Pistonshad raised his salary, it w’asnt close to the deal that Foreman was promising.

Dave jumped to the new league, inking a deal worth $500,000 for three years. He began to regret the decision when Foreman announced the team would not be moving to D.C., but instead to Norfolk, Virginia. Dave realized that this gave him a loophole to opt out of his contract. Before he did, he renegotiated a three-year deal with Pistons for almost the same money.

Unfortunately, the Pistons bottomed out in 1969–70. They won 31 times and finished in the basement. The lone bright spot was Walker, who blossomed into a 20-point scorer in his third NBA campaign. He and Dave—who averaged 22.0 per game—gave the team a sharpshooting backcourt that caused many fans to lament in jest that it was a shame the game was only played with one basketball. However with Hairston shipped to the Lakers and Bellamy to the St. Louis Hawks, there wasn’t much else to laugh about,

The Pistons appeared to catch a break the following season with the creation of the Midwest Division. The NBA expanded from two divisions to four (the Central was added, too), and Detroit now found itself in a four-team group that included the Bucks, Chicago Bulls and Phoenix Suns. Detroit finished with 45 victories, which should have been good for second place and a playoff berth, but the Suns and Bulls went from losing records to winning ones, too. The Pistons had the distinction of being the NBA’s winningest last-place team.

Dave Bing, press photo

Detroit fans were able to look past this statistical anomaly because their horrid record from 1969–70 enabled them to pluck center Bob Lanier out of the draft. Lanier transformed the Pistons into a formidable team. While the bug guy learned the league, Dave boosted his average up to 27.0 per game and led the team in assists once again. Among the highlights for Dave that year was a 54-point explosion against the defense-minded Bulls. No player in the NBA had more points in a game that season.

Lost in the offensive outburst was the fact that Dave was an exceptional defender. As he liked to remind people, one-on-one basketball ranked second only to political wheeling and dealing as the favorite activities in his old hometown. Dave lived by three simple rules—if your man can’t get the ball, he can’t score; if he does get the ball, force him take an uncomfortable shot; and if you have to loaf, do it on offense, not on defense.

What should have been a banner year in 1971–72 was a soul-crusher for Detroit. On the eve of the season, in an exhibition game with the Lakers, Dave was inadvertently jabbed in his right eye. He thought his eye was just scratched and even played in Detroit’s season opener. But the next morning he could barely see anything out of the eye. Dave had suffered a detached retina, which doctors were able to repair. They warned him, however, that he was at risk for permanent blindness in one or both eyes if he continued to play basketball.

Very few people in the medical profession or in basketball believed that Dave would ever be as effective again. He basically had no peripheral vision, and the bright lights of pro arenas obscured his field of vision. Yet Dave returned two months later to drop 21 on the Knicks his first night back. He scord better than 20 a game for the year. Lanier and Walker picked up the slack as best they could wtih Dave on the shelf, but the Pistons finished 26–56 under three different coaches. Ironically, Dave’s defense had been most noticeable when he wasn’t in the lineup. Something was clearly missing for the Pistons on the court, and it didn’t return until Dave did.

To the Pistons’ credit, they knew a good thing when they had one. After the first coaching resignation of the season, the team asked Dave if he would like to take the reigns. Dave graciously refused, and the team inked Earl Lloyd as their interim guy.

Ray Scott, Dave’s teammate during his rookie year, was hired to coach of the Pistons in 1972–73. After a shaky start, Detroit played well enough down the stretch to finish 40–42. Lanier was now an elite center, and Dave was good for 20 points more often than not. Unfortunately, the team lacked a third option. Walker had been traded to the Houston Rockets for Stu Lantz, who lost his scoring touch and then proceeded to break his wrist.

The following year, the Pistons continued their rise toward respectability. Dave worked with a pair of scrappy, young guards—Chris Ford and John Mengelt—while Lantz continued to nurse his injuries. Dave focused less on scoring and more on running the offense. The result was a fabulous 52–30 record for the Pistons and a Second-Team All-NBA nod for Dave.

The Pistons faced the Bulls in the first round of the playoffs and played a brutal seven-game series that came down to the final seconds of the decider. Chicago prevailed 96–94. Detroit took some satisfaction in watching the exhausted Bulls get swept in their next series.

The Pistons took a step backwards in 1974–75, falling to 40–42. Dave, now 31, was still a lethal scorer and as usual led the team in assists. Detroit made the playoffs and played Bill Russell’s Seattle Supersonics in the first round in a three-game set. Seattle had homecourt advantage by virtue of a better record, and they used it to win two games to one. Dave had 29 assists in the three games.

Dave Bing, 1971 Topps

Despite Dave's smart passing, the Pistons decided they needed a younger playmaker. When Dave asked for a chance to finish his career at home, Detroit accommodated his wishes over the summer by trading him and a draft pick to the Bullets for point guard Kevin Porter.

Dave had laid down strong roots in Detroit but was happy to go to a perennial winner. In D.C. he joined Phil Chenier in the backcourt. Elvin Hayes, Truck Robinson and Wes Unseld anchored the frontline. One of Dave’s best moments came that February, when he came off the bench in the All-Star Game to lead the East from a halftime deficit to a 123–109 victory. Dave made seven of 11 shots from the floor and finished with 16 points, four assists and three rebounds to take MVP honors.

The Bullets finished second in the Central with 48 wins in 1975–76. Coach K.C. Jones gave Dave all the playing time he wanted. He finished the year with a 16.2 average. He also led the Bullets in assists, finishing fifth in the league. In the playoffs, washington lost inexplicably to the Cleveland Cavaliers in seven games. Two of the Bullets' four losses were by a single point. Game 7 slipped from their grasp in the final seconds, 87–85.

In 1976–77, Dave saw his first significant bench time as a pro. Now 33-years-old and experiencing vision problems, he averaged just 24 minutes a game. The man who usurped his playing time was 24-year-old Tom Henderson, acquired at midseason for Robinson in a trade with the Hawks. Dave still put up double-figures in scoring and chipped in four assists a game, but by playoff time he was little more than an afterthought. He barely played in Washington’s first-round triumph over the Cavs and subsequent loss to the Rockets in the next round.

Dave felt he had enough in the tank to contribute as a bench player, but the Bullets did not agree. They waived him in September of 1977. Dave caught on with the aging Celtics, and ended up getting a ton of minutes after Jo Jo White was injured and Charlie Scott was dealt to the Lakers. He averaged 13.6 points a game. The Celtics finished 32-50 and would use their high draft pick on Larry Bird. After the season, Dave and John Havlicek both decided to call it quits.

Dave was more than ready to take on his next challenge—the business world. Throughout his career he had read books on business, industry and finance. During the off-season, he would take jobs with major corporations to acclimate himself to the business environment. Over the years he had worked at a bank, a car manufacturer and a steel company. In 1978, Dave took a job with a steel company and worked in every department, from the warehouse to sales and marketing to the corporate office.

In 1980, Bing Steel was born. It nearly went belly-up in its first year, but turned a profit the following year. Later Dave would buy a metal-stamping business and a construction company. They were folded into a larger entity called the Bing Group. By 1990, Bing Steel’s annual sales were north of $60 million, making the company the 10th largest black-owned corporation in the U.S.

Dave Bing, 1976 Topps

That same year Dave got the call he’d be waiting for, informing him of his induction into the Basketball Hall of Fame. Oscar Robertson praised him for his professionalism, class, dignity and humanity when he introduced him to the crowd in Springfield during the induction ceremony. In 1996, Dave was among those honored as the 50th greatest players during the NBA’s 50th Anniversary celebration.

Dave’s business empire continued to expand. He was a highly visible and deeply involved civic leader in and around the Motor City. When Detroit announced that its school’s would have to cut Phys Ed programs if a new budget wasn’t passed, Dave raised over $350,000 to ensure their survival.

In the fall of 2008, Dave announced that he would enter the mayoral race for the following year. In February of 2009, he finished first in the primary. In May, Detroit held a special election to fill its vacant mayor’s office after Kwame Kilpatrick resigned. Once again, the people of Detroit made Dave Bing their man.