Daniel Webster biography

Date of birth : 1782-01-18

Date of death : 1852-10-24

Birthplace : Salisbury, N.H.

Nationality : American

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-02-17

Credited as : Statesman and orator, lawyer, spokesman for the Northern Whigs

Daniel Webster, a notable orator and leading constitutional lawyer, was a major congressional spokesman for the Northern Whigs during his 20 years in the U.S. Senate.

Daniel Webster was born in Salisbury, N. H., on Jan. 18, 1782. After graduating from Dartmouth College, he studied law and was admitted to the bar in 1805. He opened a law office in Portsmouth, N. H., in 1807, where his success was immediate. He became a noted spokesman for the Federalist point of view through his addresses on patriotic occasions. In 1808 he married Grace Fletcher.

Elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1813, Webster revitalized the Federalist minority with his vigorous attacks on the war policy of the Republicans. Under his leadership the Federalists (with the help of dissident Republicans) often successfully obstructed war measures. After the War of 1812 he advocated the rechartering of the Bank of the United States, but he voted against the final bill, whose provisions he considered inadequate. As the representative of a region where shipping was basic to the economy, he voted against the protective tariff.

Webster's congressional career ended temporarily in 1816, when he moved to Boston. As a result of his success in pleading before the U.S. Supreme Court, his fame as a lawyer grew, and soon his annual income rose to $15, 000 a year. In 1819 he experienced a notable victory for the trustees of Dartmouth College, who were seeking to prevent the state from converting the college into a state-supported institution. Chief Justice John Marshall's opinion in the Dartmouth College case was not so much colored by Webster's emotion-charged argument as by Marshall's determination to take the opportunity to further bolster the contract clause. A few weeks later Webster secured an even greater triumph in defending the Bank of the United States in McCulloch v. Maryland. On this occasion Marshall drew from Webster's brief the doctrine that the power to tax is the power to destroy. In 1824 Webster was also successful on behalf of his clients in Gibbons v. Ogden.

When Webster returned to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1823, his speeches in behalf of the popular cause of the Greek revolution attracted national attention. President James Monroe, however, was able to prevent the passage of Webster's resolutions announcing American sympathy for the rebels. From 1825 to 1829 Webster was one of the staunchest backers of President John Quincy Adams, endorsing Federal internal improvements and supporting Adams in his conflict with Georgia over the removal of the Cherokee Indians.

Upon his election to the Senate in 1827, Webster made the first about-face in his career when he became a proponent of the protective tariff. This shift reflected the growing importance of manufacturing in Massachusetts and his own close involvement with factory owners both as clients and as friends. It was largely due to his support that the "Tariff of Abominations" was passed in 1828. His first wife died shortly after he entered the Senate, and in 1829 he married Catherine Le Roy of New York.

In January 1830 Webster electrified the nation by his speeches in reply to the elaborate exposition of the Southern states'-rights doctrines made by John C. Calhoun's close friend Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina. In memorable phrases Webster exposed the weaknesses in Hayne's views and countered them with the argument that the Constitution and the Union rested upon the people and not upon the states. These speeches, delivered before crowded Senate galleries, defined the constitutional issues which agitated the nation until the Civil War.

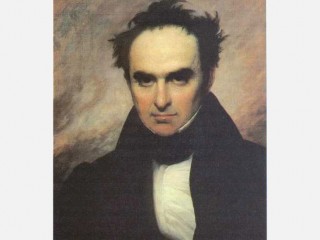

Webster was at the height of his powers in 1830. Regarded by contemporaries as one of the greatest orators of the day, he delivered his speeches with tremendous dramatic impact. He modulated his voice, speaking at one moment in stentorian tones, the next in a whisper. Yet, in spite of his emotional style and the florid character of his oratory, he rarely sacrificed logic for effect. His striking appearance contributed to the forcefulness of his delivery: tall, rather gaunt, and always clad in black; his face was dominated by deep, luminous black eyes under craggy brows and a shock of black hair combed straight back. As he grew older, his figure remained erect, but his eyes seemed to be more cavernous and to burn with greater intensity.

In private Webster was less formidable. He was fond of convivial gatherings and was a lively talker, although at times given to silent moods. His taste for luxury often led him to live beyond his means. While his admirers worshiped the "Godlike Daniel, " his critics felt that his constant need for money deprived him of his independence. During the Panic of 1837, he was in such desperate circumstances as a result of excessive speculation in western lands that only loans from business friends saved him from ruin. Again, in 1844, when it seemed that financial pressure might force him to leave the Senate, he permitted his friends to raise a fund to provide him with a supplementary income.

Although Webster was one of the leaders of the anti-Jackson forces which coalesced in the Whig party, he un-hesitatingly endorsed President Andrew Jackson's stand during the nullification crisis in 1832. In 1836 the Massachusetts Whigs named Webster as their presidential candidate, but in a field against other Whig candidates he polled only the electoral votes of Massachusetts. In recognition of his standing in the party and in gratitude for his support during the campaign, President William Henry Harrison appointed him secretary of state in 1841. He continued in this post under John Tyler, who succeeded to the presidency when Harrison died a month after the inauguration. Webster was the only Whig to remain in the Cabinet after Tyler refused to approve the party program formulated by Henry Clay. Webster stayed on in the hope of using Tyler's influence to build up a following which would ensure his nomination as Tyler's successor. He won general approval for his skill in settling the Maine-Canada dispute in the Webster-Ashburton Treaty in 1843. This dispute had been a major source of Anglo-American tension for nearly a decade. He also sent Caleb Cushing to the Orient to establish commercial relations with China, although he was no longer in office when Cushing concluded the agreement. Late in 1843 Webster, feeling that he no longer enjoyed Tyler's confidence, yielded to Whig pressure and retired from office.

In spite of his disappointment at not receiving the presidential nomination in 1844, Webster actively campaigned for Henry Clay, his archival within the party. On his return to the Senate in 1844, Webster opposed the annexation of Texas and denounced the expansionist policies that culminated in the war with Mexico. After the war he worked to exclude slavery from the newly acquired territories and voted for the Wilmot Proviso. Yet, when confronted by the crisis precipitated by California's application for admission to the Union as a free state in 1849, he dismayed his constituents by supporting Clay's compromise.

Although Northern businessmen, desiring domestic tranquility, approved Webster's speech of March 1850 in defense of the new Fugitive Slave Law, the average citizen was outraged. Webster again became secretary of state in July 1850, in Millard Fillmore's Cabinet. In 1852 he lost his last hope for the presidency when the Whigs passed over him in favor of Gen. Winfield Scott, a former Democrat. Deeply outraged, he refused to support the party candidate. He died just before the election on Oct. 24, 1852.