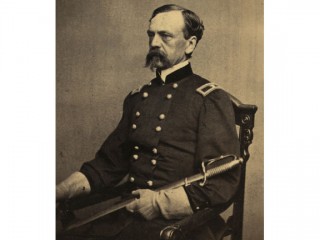

Daniel Sickles biography

Date of birth : 1819-10-20

Date of death : 1914-05-03

Birthplace : New York City, New York, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2011-02-13

Credited as : Politician, Union general, New York's Central Park

Daniel Sickles led a colorful and controversial life. He was a primary figure in the creation of New York's Central Park. Sickles may have been one of the first persons to use the insanity defense when charged with murder. He played a pivotal role in the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. Sickles also served as a military governor of the Carolinas and minister to Spain.

Daniel Edgar Sickles was the only child born to George Garrett Sickles and Susan Marsh Sickles on October 20, 1819 in New York City. The date of his birth has sometimes been incorrectly reported as 1825 and stated as such by Sickles himself. This is perhaps because of his marriage to a woman less than half his age. However, most historical records not based on the oral tradition of the family suggest that the date of 1819 is actually correct. It is rather fitting that even the birth date of this notorious character has been uncertain, for controversy was the path that his entire life would follow.

His father was a real estate speculator whose finances waxed and waned. When Sickles was a youngster, his parents were able to afford to send the young boy to a private school in Glens Falls, New York. However, he fled the school after being given a whipping for breaking rules. He worked for a local newspaper as a printer for over a year. During this time, his parents visited him with a man whose household was going to have an important impact on Sickles' future. Lorenzo L. Da Ponte was in his thirties and a professor at the University of the City of New York when they met. He persuaded Sickles to return to his parents' home in New York. After a time, they sent Sickles to a farm in New Jersey, from which he ran away. He traveled to work as a printer in Princeton and then moved to Philadelphia. His parents finally found him and let him know that he could come back to New York and they would pay for his education.

Sickles agreed, on the condition that he be allowed to live with Lorenzo L. Da Ponte and his elderly, colorful father. This arrangement was worked out and Sickles, almost 20 years of age at this point, spent several years in the Da Ponte household. The elder Da Ponte had adopted a teenaged girl who married one of the family's visitors from Italy, Antonio Bagioli. The two produced a daughter they called Teresa, in 1836. Sickles lived with the Da Ponte family, played with Teresa and took some classes at the university.

The elder Da Ponte died in 1838 and his son succumbed to tuberculosis two years later. Sickles became distraught at the graveside of the younger Da Ponte. According to Nat Brandt, in his book The Congressman Who Got Away with Murder, his friends were afraid that he "might do some further violence to himself, and that his mind would entirely give way." Two days later, he was almost light-hearted when another friend met him, a change of behavior that stood in stark contrast to the exhibition of desolation he had shown days earlier. This unusual behavior would be recalled years later when Sickles was on trial for murder.

After the death of Lorenzo L. Da Ponte, Sickles studied law with Benjamin F. Butler, a politically well-connected lawyer. Shortly thereafter, he opened his own law firm. His father began to study with him, eventually becoming a lawyer himself. Despite his interest in the law and politics, Sickles' character was not unsullied. He had been indicted in 1837 for "obtaining money under false pretenses," according to Nat Brandt. He faced several similar charges in the next few years, for which he was never prosecuted. These sorts of claims would plague him until the end of his life. At the age of 92, Sickles was accused of misuse of funds that had been collected for the monuments on Gettysburg field.

Sickles had friends from all backgrounds, from rowdy to respectable. He helped them whenever he could, perhaps to further his own career. He was elected to the New York Assembly in 1847 and became active in Tammany Hall politics for the next few years. In 1953, Sickles was sent to London as secretary to the legation and left for England on August 6 of that year. He served in this post until December 1854.

On September 27, 1852 Sickles married Teresa Bagioli, the girl who had also been part of the Da Ponte household. She was 16 years old at the time of their marriage and he was almost 33. A daughter, Laura, was born to the couple in the following year. As the date of this daughter's birth is unclear, it is speculated that Teresa was pregnant before the wedding ceremony. The family followed him to London in the spring of 1854. Sickles left his post in London on December 16, 1854. In 1855, he was elected to the New York State Senate and soon began work on a project he had begun before he left for England.

Sickles had, in his own words in Brant's historical study, organized "a consulting committee of twenty-four gentlemen, prominent in our municipal social life, with whom I was in the habit of conferring upon all questions of importance." He gathered all the park advocates to agree on a centrally located site of 750 acres rather than a smaller site in a less accessible area. He persuaded the City Council that they needed a larger site to accommodate a growing city and convinced the governor to sign legislation needed to establish the park. At first Sickles had an eye on personal gain, as he and some friends had purchased building lots near the park site. Although this group fell apart, Sickles continued to work on establishing the park, even though he was not to benefit financially in the way he had envisioned.

The site itself was boulder-filled, had no trees and large parcels of the land were covered by swamps. Lakes were dug, trees were planted, carts brought in dirt to cover the boulders, roads and bridges were constructed. The site was transformed. Sickles contributed exotic creatures from his travels for the Central Park Zoo.

In November of 1856, Sickles was elected to represent the third congressional district of New York in the U.S. Congress. He took a house in the most exclusive neighborhood of Washington, D.C., Lafayette Square, and established his family there while Congress was in session. The social functions in the city were numerous; Teresa Sickles held a reception every Tuesday morning and a dinner every Thursday night. She was expected to attend many similar functions each week, with or without her busy husband. It was the custom in the city to be escorted to these functions by one of the many bachelors. Unfortunately, perhaps due to Sickles' neglect and Teresa's boredom, she began an affair with Philip Barton Key, the son of Frances Scott Key.

When Sickles learned of the affair he became distraught and summoned several friends to his house. At the same time Key appeared across the street in Lafayette Square, and was pointed out to Sickles by one of his visitors. As was his usual pattern, Key began signaling Teresa with a white handkerchief. Brandt tells us that Sickles' friend, Samuel F. Butterworth had just advised him that if everyone knew of the affair, then "there is but one course left you as a man of honor. You need no advice." Sickles went out into the square, confronted the unarmed Key and repeatedly fired at him. At least two of the shots were at point-blank range, killing Key. Butterworth, who was nearby, made no effort to stop Sickles.

Sickles was taken to jail. His trial was set for April 4, 1859. Sickles had no less than eight lawyers representing him. These included some New York friends who were working for free and the renowned criminal lawyer, James Brady. The team amassed as much evidence as possible against Philip Barton Key and Teresa Sickles, putting their actions on trial. The argument used in the trial was that there had not been, according to Brandt's reports of the defense argument "sufficient time for his passion to cool," and that his "mind was obviously affected."

Insanity had been used as a defense before, but never as a condition that would fade within a period of time. Temporary insanity was a new defense. However, Sickles' past behavior at the funeral of Da Ponte and his seemingly quick recovery two days later established a consideration of his behavior that could be termed in the modern phrase to be "temporary insanity." On April 26, 1859, the final arguments were given. The jurors left the courtroom around 2 p.m. to deliberate. They returned one hour later with the verdict. Sickles was found not guilty.

Despite public opinion, Sickles reconciled with his wife. However, he remained away from home as much as ever. Teresa Sickles left Washington and Sickles came back to finish his term. Knowing that he would not be able to win another term in office, Sickles finished his term and turned to other projects. His wife, never quite well after the scandal, contracted a cold which worsened. She fell into a coma and died on February 5, 1867, at the age of 31.

After his term in Congress ended, Sickles had raised enough men in the state of New York to get himself deemed an army officer, though Congress at first turned down his appointment. With President Lincoln's help, he finally was approved and his men were able to join the troops fighting for the Union in the spring of 1862.

Sickles' actions were controversial at Gettysburg, one of the pivotal battles of the Civil War. He failed to put his men into the position that Major General George Mead had suggested, but positioned them forward of the line instructed. He repeatedly communicated with Mead about his position and Mead even had General Hunt inspect the position with Sickles. According to William Glenn Robertson, in his essay "Daniel E. Sickles and the Third Corps" (from the book The Second Day at Gettysburg), Hunt noted that the higher Peach Orchard position that Sickles wished to occupy had advantages, especially if they wished to mount an offensive from the left but it also had its disadvantages: "the line was too long, the resulting salient could be attacked simultaneously from two directions, and both flanks of the Third Corps would be in the air." By the time Mead arrived, the southern troops were beginning to fire on Sickles' men and it was too late to move. Mead kept sending reinforcements to the line. However, by the end of the day, though the line had held, thousands of men had fallen. Sickles himself was forced to leave the battlefield due to the wounding of his leg, which was subsequently amputated.

Some say that, though he lost thousands of men during the fighting, he was responsible for the success of the battle for the Army of the Potomac. Others say his actions almost lost the battle for the northern troops. It is probable that Sickles' action helped the army hold the ground that Mead had intended to hold originally, by keeping the line forward of the ground that was crucial to be held. However, Sickles definitely did not obey orders in the strictest sense, especially if he fully understand those orders. These are the contentions of the historians, and there is much more that has been argued in print. Sickles himself was an outspoken man who lived to be 94 years of age, well beyond most others who disagreed with him. Thus his version of events came to be widely publicized during his lifetime.

Sickles went on to become military governor of the Carolinas during the restoration period after the Civil War, then minister to Spain. He established Gettysburg battlefield as a memorial in later years, encouraging both members of the former Northern and Southern armies to commemorate their dead. Sickles married again while in Spain but lived apart from his wife, the former Caroline Creagh Sickles, and their children for almost 30 years. He returned to New York while she remained in Europe. Laura, his eldest daughter, died at the early age of 38.

Sickles, died in New York City on May 3, 1914, at the age of 94. He was a dynamic figure who had aroused much controversy during his lifetime.