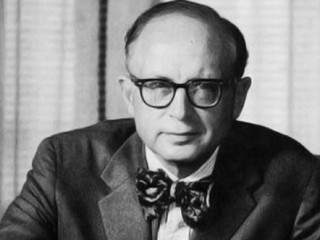

Daniel J. Boorstin biography

Date of birth : 1914-10-01

Date of death : 2004-02-28

Birthplace : Atlanta, Georgia, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-02-13

Credited as : Historian, attorney and writer, The Mysterious Science of the Law

American historian Daniel J. Boorstin was a scholar with broad interests, best known as an advocate of a conservative, "consensus" interpretation of American history. He became Librarian of Congress in 1975.

Daniel J. Boorstin was born on October 1, 1914, in Atlanta, Georgia, but grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His writings later reflected some of the spirit of his childhood home, a booming oil city full of optimism and entrepreneurial possibilities. After graduating from high school at age 15, he entered Harvard University where he won the Bowdoin Prize for his senior honors essay in 1934. Awarded a Rhodes scholarship, he studied law at Oxford University's Balliol College and achieved a prestigious double first—first-class honors in two degrees, a B.A. in jurisprudence (1936) and a Bachelor of Civil Laws (1937).

Boorstin returned to the United States in 1937 and spent a year at Yale Law School, which subsequently (1940) awarded him a Doctor of Juridical Science degree. From 1938 to 1942 he taught legal history, American history, and literature courses at Harvard and Radcliffe. Meanwhile, like many American idealists and intellectuals in the 1930s, he became interested in Marxism. In 1938 he joined the Communist Party, but he left it the following year because of disillusionment with events in Europe, notably the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact of 1939. Years later, Boorstin angered many radicals and liberals by testifying before the House Un-American Activities Committee and agreeing to provide the committee with the names of his former Party comrades.

Boorstin was admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1942, and for a few months he practiced law as an attorney for a federal agency, the Lend-Lease Administration. Later in 1942 he resigned his government post to accept a teaching position at Swarthmore College. In 1944 he joined the faculty of the University of Chicago, where he remained for the next 25 years.

Boorstin's first book, The Mysterious Science of the Law (1941), described how Sir William Blackstone's Commentaries (1765-1769) were shaped by practical experience with the law rather than by a priori reasoning about social values. In a second book, The Lost World of Thomas Jefferson (1948), Boorstin argued that Jefferson was not, as most Jeffersonian scholars claimed, a speculative philosopher, but a man who derived insights from his experience with concrete situations.

Boorstin's belief that there was a striking contrast between American and European ways of thinking, and his conviction that American pragmatism was vastly superior to European devotion to abstract philosophical systems, became even more explicit in The Genius of American Politics (1953). In this slim volume Boorstin asserted that the American experience was in many respects exceptional. "Givenness" was the term Boorstin used for the quality that set Americans apart. The natural abundance of the land gave Americans exceptional opportunities and encouraged a faith in upward mobility. The fortuitous given in history was that American society had not had to pass through a feudal phase, with the result that the nation's body politic had been free of conflicts between supporters of an old regime and advocates of republican and bourgeois ideals. American realities, if judged by the standard of known historical precedents, were so close to ideal conditions that utopian ideological schemes would not appeal to Americans. The "is" of American life would be taken as the "ought." Thus, a national consensus on the virtues of moderate liberalism and entrepreneurial optimism became the hallmark of American life. Even the Civil War had not, according to Boorstin, broken these broad continuities or produced fundamental changes in American institutions.

Boorstin's description of the American past was a sharp departure from the views of the previous generation of historians, the so-called progressives, for whom conflict and change were the crucial themes in the nation's history. Boorstin, therefore, was soon recognized as one of the leading proponents of a conservative, "consensus" interpretation of American life. Critics were quick to challenge his perspective, asserting that he ignored instances of deep-seated economic and ethnic conflict while giving inadequate attention to the many Americans whose experience did not fit neatly with his nationalist claims for the United States as a land of opportunity.

The fullest expression of Boorstin's interpretation of American life may be found in his three-volume history of the United States. Some reviewers complained that the trilogy was seriously deficient because Boorstin said little about political and military history. However, the virtual absence of these topics was consistent with his view that the truly important themes in the American past were the social history of pioneering, invention, entrepreneurship, and the like.

In volume one, The Americans: The Colonial Experience (1958), Boorstin offered numerous examples in support of his thesis that the givens in the American environment, the country's vast size and wealth of its resources, quickly broke down or transformed every utopian scheme—Puritan Massachusetts, corporate Virginia, Penn's Pennsylvania, and Oglethorpe's Georgia—that Europeans attempted to establish in the New World.

In his second volume, The Americans: The National Experience (1965), which covered the period from the Revolution to the Civil War, Boorstin described the United States as a nation of practical folk who, in spreading westward across the continent, developed a faith in republicanism and individualism because the virtues of those ideas were daily demonstrated in their lives.

Finally, in The Americans: The Democratic Experience (1973) Boorstin gave his version of American life since the Civil War. It was still a story with many heroes, go-getter businessmen such as Gustavus Swift, and trend-setting inventors such as Thomas A. Edison. Nevertheless, the book closed on a somber note as Boorstin decried some of the trends he observed in 20th-century American life, especially what seemed to him the baneful influence of consumer culture and the mass media.

Boorstin's criticisms of certain aspects of contemporary American life were not entirely new themes in his writings. In 1962 he had published The Image: or, What Happened to the American Dream (reissued as a paperback in 1964 with a new subtitle, A Guide to Pseudo-Events in America), in which he charged that the mass media were cutting Americans off from the concrete experiences that had been the source of their earlier national greatness and plunging them into an unreal world of pseudo-experiences. Similarly, Boorstin had been deeply troubled by the outburst of radical protest that swept university campuses in the late 1960s. In his book The Decline of Radicalism: Reflections on America Today (1969) he had harsh words for the New Left radicals, asserting that they were advocating dissent, which tended to divide and destroy, rather than practicing disagreement, which allowed for discussion and, eventually, for agreement through compromise.

In 1969 Boorstin left the University of Chicago and joined the staff of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In 1975 he was appointed Librarian of Congress by President Gerald Ford and served in that position until 1987. In spite of his heavy administrative duties, he continued to write. His book The Discoverers (1983) was an ambitious project in which he traced the history of mankind's pursuit of knowledge about the world from Greek times to the present.

Throughout his life, Boorstin received much acclaim for his historical scholarship. His three-volume history of the United States, The Americans, was awarded the Bancroft, Parkman, and Pulitzer Prizes. For his effort on The Discoverers he received the History of Science Society's Watson Davis Prize. Boorstin was the beneficiary of more than 50 honorary degrees and was decorated by the governments of France, Belgium, Portugal, and Japan. His work also earned him the Phi Beta Kappa Distinguished Service to the Humanities Award and the Charles Frankel Prize from the National Endowment of the Humanities. In 1989 Boorstin received the National Book Award for Distinguished Contributions to American Letters from the National Book Foundation.

In addition to his tenure at the University of Chicago, Boorstin also served as visiting professor at the University of Rome, the University of Geneva, the University of Kyoto, and the University of Puerto Rico. At the Sorbonne, in Paris, he was the first incumbent chair of American History.

Although his books proved exceptionally popular, Boorstin often stated that he wrote for the pleasure of writing rather than for compensation. As he entered his eighties, he continued to write and travel the lecture circuit. In 1992 he published The Creators which chronicled man's achievements in the arts. In 1994 he published a collection of essays on the role that the unexpected plays in history titled Cleopatra's Nose: Essays of the Unexpected, and in 1995, The Daniel J. Boorstin Reader, which included selections from most of his books. In all Boorstin authored or edited more than 26 works, which have since been translated into more than 25 languages.