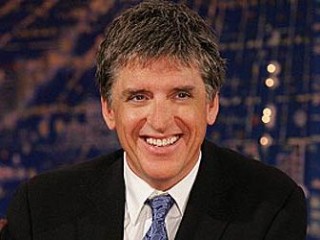

Craig Ferguson biography

Date of birth : 1962-05-17

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Glasgow, Scotland

Nationality : Scottish-American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2011-05-17

Credited as : Actor and comedian, screenwriter, Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson

1 votes so far

Born on May 17, 1962 in Glasgow, Ferguson grew up in a blue collar family of six in nearby Cumbernauld. He dropped out of high school to play drums for the punk band The Bastards from Hell and, as he later admitted, "mainly to drink." After two years with the band - later renamed Dreamboys - he realized he enjoyed the on-stage banter more than the actual musical performance. Incorporating a punk ethos, he tried his hand at stand-up and developed a following as his "Hitler" character, a rabid, raging hater of all things -sort of an über-Scottish Lewis Black, but without the charm. Comedy led to his first dip into TV with a stint writing for the BBC's popular "The Russ Abbot Show" (1986-1990).

He parlayed his stage talents onto the small screen for the first time with a guest shot on the popular BBC sci-fi comedy "Red Dwarf" (BBC2, 1988-1999), and began scrolling up supporting roles in BBC movies such as "Dream Baby" (1989) and "The Bogie Man" (1992). In between, he tried his hand in Hollywood, managing to net a 1987 stand-up set as Bing Hitler on Showtime's "Just for Laughs II" special, as well as a lead in a pilot for CBS called "High." But CBS passed on the show, and a discouraged Ferguson returned to the UK. There, the next few years would see his name on a number of - by his own estimate - forgettable TV sketch comedy outings, and, though he built some renown - at one point dating ex-"Bond Girl" Fiona Fullerton ("A View to a Kill," 1985) - all was far from well.

Behind the laughs, Ferguson had slid into a cycle of destructive behavior - a broken marriage, drug and alcohol abuse, battles with personal demons. He hit a personal nadir, as he would later relate in one of his milestone "Late Late Show" monologues, one Christmas when he awoke, soaked in his own urine, in a room above the London bar in which he had drunk the previous night away. It was then that he decided to commit suicide by jumping off the Tower Bridge in London. The bartender convinced Ferguson to stick around, at least long enough to imbibe a tall sherry, and, as Ferguson later told it, "one thing led to another and I forgot to kill myself."

That, he said, began a catharsis that spurred Ferguson to check himself into rehab, get clean and, in 1995, to roll the dice once more in Hollywood. Moving to Los Angeles, he earned a recurring role on Steven Spielberg's star-studded Saturday morning (and cult fave) cartoon "Freakazoid!" (The WB, 1995-97), as over-the-top stereotype Scot, Roddy MacStew, the title character's mentor. He also forged through network sitcom cattle calls to win a supporting role in the forgettable, short-lived "Maybe This Time" (ABC, 1995-96), as well as a small recurring role in the Nancy Travis vehicle "Almost Perfect" (CBS, 1995-97).

Ferguson next landed the plum role of his supporting character resume, joining ABC's year-old hit sitcom "The Drew Carey Show" in 1996 as the title character's new English boss, Nigel Wick. Though often ancillary to the show's A-story, Ferguson's turn as the whimsically mean chief of the Winford Lauder department store made his brief stints on camera some of the show's highlights - in particular, a running gag where Wick would concoct devilishly creative new ways to randomly fire people, usually one of a run of hapless employees named "Johnson." "Gather round, everyone," he bade the office denizens one episode. "Story time. Come on . . . gather round. Once upon a time . . . Johnson was fired. And everyone else lived happily ever after. Freaked, but happily."

As the series billowed to ABC's top-rated roster, Ferguson's character expanded from giddy despot to gonzo drug-addled fetishist, but his infrequency on camera afforded him time in his trailer to work on more personal projects. In 1999, that manifested itself in the first of a run of minor films, beginning with "The Big Tease." Ferguson co-wrote and starred in the "mockumentary" that followed him as a flamboyantly gay Scots hairdresser, making a pilgrimage to LA to compete in a world coiffure competition. He next penned and starred in "Saving Grace" (2000), a contextual return to his native Britain with a story of quirky provincials that drew comparisons to "Waking Ned Devine" and "The Full Monty." It told the tale of a Cornish gentlewoman (Brenda Blethlyn) who loses her husband, finds her home at risk from his creditors and falls in with her groundskeeper (Ferguson) who convinces her to grow marijuana. The film charmed critics for the most part, and The New York Times review, though tepid, did put Ferguson on notice as "a leading contender for the title of World's Most Amusing Scot."

Ferguson took the next logical step toward a Renaissance résumé with his ensuing script, directing himself as a washed-up, besotted '80s pop star in "I'll Be There" (2003). The Warner Bros.-backed film received a smattering of buzz, mainly as the result of his co-star, opera singer Charlotte Church in her cinematic debut, playing Ferguson's just-discovered and (gasp!) super-talented love child, as well as for Ferguson's famous banning of showbiz mom Maria Church from the set. Though "I'll Be There" did snare Ferguson an "Audience Award" at the U.S. Comedy Arts Festival, the film flopped and Mrs. Church's meddling was not the only thing that left Ferguson disgruntled with the project. After the movie wrapped, he felt so inundated by Warner's heavy hand in the production, that he sat down in his hotel room and began plotting a distinctly less "collaborative" outlet for his humor, a novel. It would prove a significant motivation as Ferguson began to fear another career lull with the shuttering of "The Drew Carey Show" in 2004. But then, in the fall of 2004, CBS came knocking.

CBS stumbled upon its new "Late Late Show" host almost as a lark, going through a two-month series of on-air "auditions" after Craig Kilborn, original host of Comedy Central's flagship "The Daily Show" (1996- ), decided to call it quits after five years. The network and Letterman's production company Worldwide Pants raised eyebrows when they chose Ferguson out of field of 20 guest hosts that rotated on the show through late 2004. In January 2005, Ferguson, with a newly inked $8 million contract, began hosting "The Late Late Show with Craig Ferguson."

Some critics panned Ferguson's initial work, and few expected much from the low-rated slot long seen as CBS's attempt to simply run a token lead-out to Letterman's "Late Show" against NBC's "Late Night with Conan O'Brien." But two months into his tenure, Ferguson made the decision to buck the U.S. talk-show template. Whereas contemporaries Letterman, NBC's "Tonight Show" host Jay Leno and O'Brien began each show wholly scripted, working set piece monologues off cue-cards, Ferguson began noticing the best audience reactions came when he ad-libbed between jokes. He decided to scrap pre-written jokes altogether and wing extemporaneous monologues, highlighting his off-the-cuff sense of humor and creating a more distinct, personal voice in an otherwise by-the-numbers programming genre.

The decision would yield a poignant moment in American television and, to be sure, a galvanizing event in Ferguson's success. On Jan. 30, 2006, just back from mourning the death of his cancer-stricken father in Scotland, he told his audience he could not bring himself to just do a regular show with "my usual complaining about Starbucks or my half-arsed impression of Sean Connery." He related his visit and candidly recalled the contentious relationship with the late Robert Ferguson in an uninterrupted, unscripted 15-minute eulogy. The show would earn him an Emmy nomination later that year.

In addition to witnessing his entrenchment in late-night TV, 2006 saw Ferguson bolster his Renaissance credentials further as his novel, Between the Bridge and the River was published to critical acclaim rarely heaped on celebrity literary dalliances. Following the intermingling odysseys of five requisitely quirky, personal-demon-beset characters, the book wove in autobiographical elements with cutting allegorical send-ups of contemporary religion, Hollywood excesses and American commercial culture. The black, oft-violent comedy earned him raves, notably from Publisher's Weekly, which called the novel "a tour de force of cynical humor and poignant reverie, a caustic yet ebullient picaresque that approaches the sacred by way of the profane."

If his literary work evinced a darker tone to his sometimes eviscerating on-air critiques of show business and political absurdities, Ferguson showed a thoughtful, more empathetic side in early 2007 with another signature monologue. In February, with onetime pop wunderkind Britney Spears thick amid another much-publicized flare-up of self-destruction, culminating in shaving her hair off - and with his late-night contemporaries feasting on Spears' foibles - he declared enough. Ferguson, with unflappable but almost sweet self-deprecation, told the nation his own story of addiction and his abortive Tower Bridge suicide plan. Having just celebrated the 15th anniversary of his getting sober, he said he would not just pour salt on what might well be psychological wounds of people like Spears, who, he said, "clearly needs help." "For me, comedy should have a certain amount of joy in it. It should be about attacking the powerful - the politicians, the Trumps, the blowhards - going after them," he told his audience. But since addiction did not discern, he said, his show would. "You can't beat it with money," he said. "If you could beat this with money, rich people wouldn't die."

It seemed ironic for a guy who shared so much of his own life with his audience - from his second divorce in 2007 to his self-purported endowment and gastrointestinal issues - to declare others' off limits, especially in a line of work that drew so heavily on the pop-cultural zeitgeist. But the buzz around Ferguson's nearly irrepressible honesty, Scots charm - most particularly informing his routine references to his audiences as "naughty monkeys" - and even his rare (for American TV) erudition went reflected in his steady ascent in the ratings, luring upwards of 2 million viewers per broadcast, putting CBS and NBC's late night shows in real competition for the first time. Adding to the sweetness of life, Ferguson became a U.S. citizen in February 2008, and, in April, capped his first ratings victory against O'Brien with an apropos honor: being selected to keynote the White House Correspondents' Dinner, the prestigious annual gathering of press and politicians, in Washington, D.C.

There, Ferguson noted that the event, made most famous when Comedy Central's up-and-coming fake-pundit Stephen Colbert skewered George W. Bush and the American press in 2006, was notoriously tough to book since attendees inevitably proved a tough crowd for comedians. Explaining his presence, he said it was " just another case of immigrants taking jobs that Americans don't want."