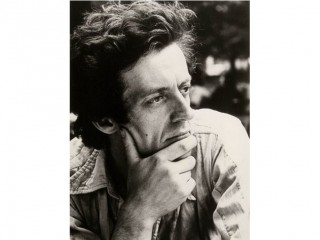

Cornelius Cardew biography

Date of birth : 1936-05-07

Date of death : 1981-12-13

Birthplace : Winchcombe, England

Nationality : English

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2011-11-01

Credited as : music composer, Scratch Orchestra,

0 votes so far

Cornelius Cardew's reputation is staked as much on his political beliefs as on his innovative compositions. His graphic scores were based on writings by the Chinese philosopher Confucius and on the views of Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong. That, as well as his participatory approach to composition and performance, reflected a deep concern with pro-working class, Communist principles that, at one point in his career, led him to renounce his early work. Cardew's evolution as a composer, musician, and political thinker was cut short by his suspicious untimely death at the hands of a hit-and-run driver in 1981. He was 45.

Cornelius Cardew began his musical education as a member of the chorus at Canterbury Cathedral, joining in 1946 and continuing through 1950. In 1953, at the age of 17, he entered the Royal Academy of Music in London. There he studied composition with Howard Ferguson and piano with Percy Waller, and developed an interest in electronic music. After his graduation from the academy in 1957, Cardew studied in Cologne, Germany, with composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, known for his electronic compositions. He continued on as Stockhausen's assistant from 1958-60, and the two collaborated on Stockhausen's multi-orchestral composition, Carré.

While in Cologne, Cardew attended concerts given by American avant-garde composer/pianists John Cage and David Tudor. These spurred his interest in experimental composition techniques, and he began writing a series of "indeterminate" pieces, including Autumn '60, Octet for Jasper Johns, Solo with Accompaniment, and Memories of You. In these pieces Cardew, like Cage before him, disregarded traditional musical notation in favor of indicating rhythms and providing directions to performers on approximate pitch. The scores did not extend complete freedom to the performers, but rather served as guides that left room for their own interpretations. "Speaking as a performer in many of Cardew's early works, it must be said that the experience was totally rewarding," wrote composer David Bedford, as quoted on the website for the London-based Contemporary Music-making for Amateurs. "Our creativity was constantly being challenged, and the empathy of the performers, channelled into producing a coherent piece of music despite sometimes sketchy and sometimes paradoxical instructions, was often remarkable." During this time, Cardew also performed regularly, focusing on works by noted American avant-garde composers, including Cage and Christian Wolff. He also learned to play guitar, and performed on that instrument in a 1957 London concert featuring Pierre Boulez's Le marteau sans maître.

Cardew returned to London in 1961 and studied graphic design, a field in which he worked intermittently for the rest of his life. He studied with Goffredo Petrassi in Rome in 1964, supported by a scholarship from the Italian government. Beginning in 1963 Cardew began to compose graphic scores, which used visual representations in place of traditional notation. Often Cardew offered little or no explanation of these graphic elements, leaving interpretation of the pieces to the broad discretion of the performers. Between 1963 and 1968, he composed his monumental graphic score Treatise, a 193-page document inspired by the German philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein's Tractus. Cardew was named a fellow of the Royal Academy of Music in 1966 and appointed a professor there the following year.

During this time he also joined the minimalist improvisational group AMM, which also featured drummer Eddie Prévost, saxophonist Lou Gare, and guitarist Keith Rowe, all jazz musicians. Cellist Rohan de Saram and pianist John Tilbury played with the group occasionally as well. Cardew helped form the Scratch Orchestra in 1969. The collective grew out of a composition class he taught at Morley College in London, and contained a large, rotating group of performers both professional and amateur, including members of AMM. "Anyone could join, provided they were enthusiastic," orchestra member Michael Parsons, a member of Cardew's Morley class, recalled in a 2002 interview with the Birmingham Post. "A lot were visual artists. The art schools were breaking down barriers, and they were often more receptive to new ideas." The group splintered in 1971 due to disparate political views, with a faction led by Cardew, Tilbury, and Rowe maintaining the name and following Marxist-Leninist political theories. Cardew's work began to show a growing political consciousness, based on Communist fundamentals, during this time. Between 1968 and 1970 he composed The Great Learning, a combined traditional and graphic score containing blocks of text based on poet Ezra Pound's translation of writings by the Chinese philosopher Confucius.

By 1974, as his adherence to Marxist thought and its emphasis on the struggles and ultimate rise of the working class deepened, Cardew immersed himself in the writings of Karl Marx and Mao Zedong. He renounced his early indeterminate scores and outlined his views in a 1974 collection of essays, Stockhausen Serves Imperialism. He began to compose works that he believed spoke of the struggles of the working class. He continued to perform in elite venues such as concert halls, but often accompanied performances of early works with disclaimers. "I have discontinued composing music in an avant garde idiom for a number of reasons: the exclusiveness of the avant garde, its fragmentation, its indifference to the real situation of the world today, its individualistic outlook and not least its class character (the other characteristics are virtually products of this)," Cardew wrote in the program notes to the score of Piano Album in 1973, as quoted in a 1998 article by Timothy D. Taylor in Music and Letters. The notes went on to say, "At a time when the ruling class has become vicious and corrupt, as it must in its final decay, it becomes urgent for conscious artists to develop ways of opposing the ideas of the ruling class and reflecting in their art the vital struggles of the oppressed classes and peoples in their upsurge to seize political power."

Piano Album contained arrangements of music from China, whose socialist government Cardew admired, and Ireland, where revolutionaries fought for freedom from British rule. Inspired by Mao Zedong's belief that works of art not serving the masses can be changed to do so, Cardew revised the text, though not the music, of The Great Learning in 1974. Later, however, he criticized the revision, and accompanied any performances of the piece with his own commentary, which, as quoted by Taylor, asserted that it was "inflated rubbish." Some of Cardew's working class pieces drew criticism from a compositional standpoint, which Cardew refuted in a 1975 interview in Music and Musicians. "I acknowledge there are compositional shortcomings in these pieces and I don't make any claims for them. The advantage of them is that they draw the attention of the listeners to social issues. If you have a concert of arrangements of Irish songs, it does draw attention to the culture of the Irish and also to their fight," he said.

Cardew's influence waned in the last ten years of his life, as his political views grew more extreme. On December 13, 1981, he was killed by a hit-and-run driver near his home in East London. The driver was never found, and some have theorized that Cardew was murdered because of his political beliefs. Tilbury and numerous other musicians have carried Cardew's work into the 21st century and renewed his relevance. "He's a very difficult person to sum up in a few words, but also for that reason he's constantly surprising and stimulating," Parsons told the Birmingham Post, in an article assessing Cardew's lasting influence. "He was a complex character, and very much an explorer. If he were alive today he would certainly be doing something interesting, but we don't know what it would be."

Selected discography

Solo albums:

-Great Learning Deutsche Grammophon, 1971.

-Four Principles On Ireland and Other Pieces Cramps, 1974; reissued, Ampersand, 2001.

-Thälmann Variations Matchless, 1986.

-Treatise Hat Hut, 2000.

-Chamber Music 1955-64---Apartment House Matchless, 2001.

-We Sing for the Future! New Albion, 2001.

-We Only Want The Earth Musicnow, 2002.

With AMM

-AMMusic Elektra, 1966; reissued, Matchless, 1994.

-Improvisation Mainstream, 1968.

-To Hear You Back Again Matchless, 1974.

-It Had Been An Ordinary Day In Pueblo Japo, 1979.

-Generative Themes Matchless, 1982.

-Combine and Laminates Pogus, 1984.

-Inexhaustible Document Matchless, 1987.

-Nameless Uncarved Matchless, 1990.

-Vendouvre Ambient Isolationism Virgin, 1993.

-Newfoundland Matchless, 1994.

-Live In Allentown Matchless, 1996.

-Tunes Without Measure Or End Matchless, 2001.

Selected compositions:

-Why Cannot the Ear Be Closed to Its Own Destruction? (vocal and piano), 1957.

-Arrangement for Orchestra (orchestra), 1960.

-Third Orchestra Piece (orchestra), 1960; arranged as Material (harmony instruments), 1964.

-Autumn '60 (chamber orchestra), 1960.

-Octet '61 (undetermined forces), 1961.

-3 Winter Potatoes (piano), 1961-65.

-Movement for Orchestra (orchestra), 1962.

-Ah Thel (voice and piano), 1963.

-Treatise (undetermined forces), 1963-67.

-Bun no. 1 (orchestra), 1965.

-Sextet--the Tiger's Mind (undetermined forces), 1967.

-Schooltime Compositions (undetermined forces), 1968.

-Schooltime Special (undetermined forces), 1968.

-The Great Learning (various performers), 1968-70; paragraphs 1 and 2 revised, 1972.

-The East is Red (orchestra), 1972.

-3 Bourgeois Songs (voice, orchestra, piano), 1973.

-Thälmann Variations (piano), 1974.

-Vietnam Sonata (piano), 1975.

-Mountains (bass clarinet), 1977.

-Workers' Song (violin), 1978.

-We Sing for the Future! (piano), 1981.

-Boolavogue (two pianos), 1981.

Selected writings:

-Treatise Handbook Gallery Upstairs Press, 1971.

-Stockhausen Serves Imperialism Latimer New Dimensions, 1974.