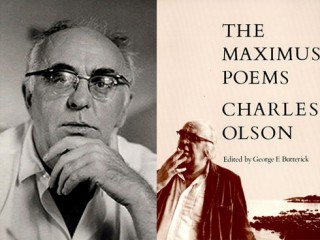

Charles Olson biography

Date of birth : 1910-12-27

Date of death : 1970-01-10

Birthplace : Worcester, Massachusetts, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-02-03

Credited as : Poet, The Maximus Poems, Call Me Ishmael

Charles Olson defined and practiced an open, kinetic poetry which influenced many of the second generation of modern poets.

Charles Olson, born in Worcester, Massachusetts was an energetic giant of a man. In his youth his energy took the form of conspicuous academic success. He was Phi Beta Kappa and a candidate for a Rhodes scholarship at Wesleyan University, where he earned a B.A. in 1932 and an M.A. in 1933 with a thesis on Herman Melville. By 1939 Olson completed course work for a Ph.D. in American civilization at Harvard University, published his essay "Lear and Moby Dick," and received his first Guggenheim fellowship to continue research on Melville. In the 1940s Olson moved away from a traditional academic career, through a disillusioning flirtation with politics, to his lifelong work as a poet. His youthful energy and scholarship came to distinguish his poetry.

Much of the political 1940s were spent in Washington, D.C., but in 1951 Olson joined Black Mountain College in North Carolina as a visiting professor, later becoming rector until financial difficulties forced the close of the college. At Black Mountain Olson found students and staff devoted to the active practice of the arts. In 1957 Olson moved to Gloucester, Massachusetts, where he had spent summers as a boy. He accepted positions as visiting professor at the State University of New York at Buffalo (1963-1965) and at the University of Connecticut (1969). Olson married twice and was the father of two children. He died from cancer in 1970.

Olson's wide reading informed his writings. Prose works, such as Call Me Ishmael (1947) and The Special View of History (1957), reveal his fascination with 20th-century man's discoveries concerning the dynamic, interactive nature of the world and man's possibilities in such a world. Influenced by Alfred North Whitehead concerning the interaction of the past and the present, Olson believed that each man could select from history what he needed to constitute a rich and useful present. Olson was further influenced by Carl Jung's integration of the world within the mind and the world without: man's lifelong task, Jung argued, was to find in external reality objects and events which can express in symbolic terms the secrets of creation locked in the unconscious. In Olson's poem "The Librarian" (1957) traditional distinctions between the mind and external reality evaporate.

In his influential 1950 essay "Projective Verse" Olson defined poetry in terms of the dynamic world his contemporaries were discovering: "A poem is energy transferred from where the poet got it … by way of the poem itself … to the reader." The poet's own energy as he writes is among that which is embodied in the poem. The syllable, Olson argued, reveals the poet's act of exploring the possibilities of sound in order to create an oral beauty. The line reveals the poet's breathing, where it begins and ends as he works. Conventional syntax, meter, and rhyme must be abandoned, Olson argued, if their structural requirements slow the swift currents of the poet's thought. The predictable left-hand margin falsifies the spontaneous nature of experience.

In rethinking the possibilities of language, Olson acknowledged his debt to Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams. Olson also valued the breadth of Pound's historical knowledge, which made available so much of the past necessary to constitute a valuable present. In Williams' attention to the precise nature of individual objects and their relations, however, Olson found an alternative to the prejudices which marred Pound's reading of history. The poem "The Kingfishers" (1949), with its ornithological details and restless search of history, signals Olson's intention to synthesize the best of Pound and Williams.

Olson wrote over 100 shorter poems now collected in Archaeologist of Morning. His most sustained effort to practice his poetic theories, however, was the Maximus Poems, a 20-year sequence published in three volumes. The poems are set in Gloucester, Massachusetts, and have as their hero the dynamic Maximus, who slowly becomes indistinguishable from Olson himself. The first volume of 39 poems was begun in 1950 and published as The Maximus Poems in 1960. Its poems are, in part, an outgrowth of Olson's earlier political interests and his communal experiences at Black Mountain. Maximus labors to found in Gloucester a community devoted to creative pursuits. Its members will be the readers of the poems, to whom Maximus hopes to transfer the same creative energy which motivates him. Finding his efforts sabotaged by capitalism's exploitation of natural and human resources, however, Maximus becomes increasingly enraged and despondent. Nonetheless, he continues to write, developing his own creative powers in order to enhance his creative possibilities in a hostile world.

Maximus Poems IV-V-VI rewards his labor. The history of man's migration west from primeval times reveals an energy to colonize which is precisely what Olson would transfer to his reader. In the tradition of Whitehead, Maximus enacts this history in order to make it a vital contemporary force. He walks through Gloucester, for example, retracing the steps of the colonists who carried western migration across the Atlantic. As the poems accumulate, Maximus pushes farther back into history and myth in order to understand ever more about the dynamics of migration. His efforts earn him a vision of the primal source of the energy which drove man west. For Maximus, this vision, found in "Maximus—from Dogtown IV," expresses in a satisfactory way the secrets of creation which are locked in the unconscious.

In Maximus Poems: Volume Three (1975) Maximus explores what he can accomplish now that he is empowered by his knowledge and vision. Because these poems were collected and arranged chronologically by others after Olson's death, the shape he would have given the volume, had he lived, is unknown. In individual poems, however, Olson as Maximus seeks new reconciliations—with his long-dead father, for example—and returns to the unfinished business of the first Maximus poems in an effort to restore Gloucester as a city full of creative possibilities. Yet the death of his wife, the distance of friends, and declining health made him feel more estranged and uncertain than in the first volume. In this, the most personal volume of the Maximus Poems, the empowered Olson and the uncertain Olson contest with one another. As death overtakes him, however, Olson resists despair by recognizing that the life he has lived in his poems may pose a sufficient alternative to the destructive capitalist norm to stand after he falls.

George Butterick provides over 4,000 annotations in his invaluable A Guide to the Maximus Poems of Charles Olson (1978). Butterick has also collected the correspondence between Olson and Robert Creeley in Charles Olson & Robert Creeley: The Complete Correspondence (6 vols., 1980-1984). Sherman Paul provides a comprehensive study of Olson's intellectual and poetic development in Olson's Push (1978). Other titles of important studies are self-explanatory: Donald Byrd, Charles Olson's Maximus (1980); Thomas Merrill, The Poetry of Charles Olson: A Primer (1982); and Robert von Hallberg, Charles Olson: The Scholar's Art (1979). Finally, there is Paul Christensen's Charles Olson: Call Him Ishmael (1979).