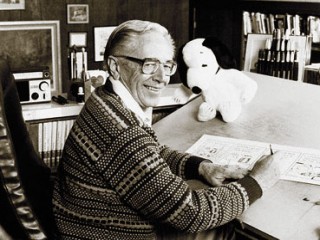

Charles M. Schulz biography

Date of birth : 1922-11-26

Date of death : 2000-02-12

Birthplace : Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-02-03

Credited as : Cartoonist, creator of Peanuts, Happiness Is a Warm Puppy 1962

Cartoonist and creator of "Peanuts", Charles M. Schulz was the winner of two Reuben, two Peabody, and five Emmy awards and a member of the Cartoonist Hall of Fame.

Charles Schulz was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on November 26, 1922, the son of Carl (a barber) and Dena (Halverson) Schulz. At school in St. Paul he was bright and rapidly promoted, which made him often the smallest in his class, a fact that may have been of psychological significance in his later development. Noting his aptitude for drawing, his mother encouraged him to take a correspondence course from the Federal School in Minneapolis.

In World War II Schulz was drafted and sent to Europe, mustering out after the war as a sergeant. He returned to Minnesota as a young man strongly imbued with Christian beliefs. For a while he free-lanced for a Catholic magazine and taught in the correspondence school, which had been renamed the Art Instruction Institute. Some of his work appeared in the Saturday Evening Post, and eventually he created a cartoon entitled "Li'l Folks" for the St. Paul Pioneer Press, signing it "Sparky," a nickname conferred on him by an uncle.

In 1950 the United Feature Syndicate of New York proposed publication of a new comic strip, which Schulz wished to call "Li'l Folks" but which was named "Peanuts" by the company. In 1950 the cartoon made its debut in seven newspapers with the characters Charlie Brown, Shermy, Patty, and Snoopy. Within a year the strip appeared in thirty-five papers, and by 1956 in over a hundred. Characters were added slowly, and psychological subtleties were much developed. Lucy, Linus, and Schroeder appeared; then Sally, Charlie Brown's sister; Rerun, Lucy's brother; Peppermint Patty; Marcie; Franklin; Jose Peterson; Pigpen; Snoopy's brother, Spike; and the bird, Woodstock. In 1955, and again in 1964, Schulz received the Reuben award from the National Cartoonists Society.

By this time Schulz' popularity was enormous and had become world-wide. "Peanuts" appeared in over 2,300 newspapers. The cartoon branched out into television, and in 1965 the classic "A Charlie Brown Christmas," produced by Bill Melendez and Lee Mendelson, won a Peabody and an Emmy award. Many more television "specials" and Emmys were to follow. An off-Broadway production, "You're a good man, Charlie Brown," staged in 1967, ran four years. In 1969, National Aeronautics and Space Administration astronauts named their command module "Charlie Brown" and their lunar lander "Snoopy." Many volumes of Schulz' work were published in at least 19 languages, and the success of "Peanuts" inspired many licensed products in textiles, stationery, toys, games, etc. Schulz also authored a book, "Why, Charlie Brown, Why?" (which became a CBS television special) to make the dreaded subject of cancer understandable to children (his mother had died of cancer during World War II).

Besides the previously mentioned awards, Schulz received the Yale Humor Award, 1956; School Bell Award, National Education Association, 1960; and honorary degrees from Anderson College, 1963, and St. Mary's College of California, 1969. A "Charles M. Schulz Award" honoring aspiring comic artists was created by the United Feature Syndicate in 1980. The year 1990 marked the 40th anniversary of "Peanuts." An exhibit at the Louvre, in Paris, called "Snoopy in Fashion," featured 300 Snoopy and BELLE plush dolls dressed in fashions created by more than 15 world-famous designers. It later traveled to the United States. Also in 1990, the Smithsonian Institution featured an exhibit titled, "This Is Your Childhood, Charlie Brown… Children in American Culture, 1945-1970."

The "Peanuts" cartoons were centered on the classically simple and touching figures of a boy and his dog, Charlie Brown and Snoopy, surrounded by family and school friends. Adults were present only by implication, and the action involved ordinary, everyday happenings, transformed by childhood fantasy.

Charlie Brown was the quintessence of ordinariness, as his name and his visible form suggest. His round head had minimal features, half-circles for ears and nose, dots for eyes, a line for a mouth, the rest of the body compressed to pint size. He was a combination of ineptness and puzzlement in the face of problems that life and his peers dealt out to him: the crabby superiority of Lucy; the unanswerable questions of Linus, a small intellectual with a security blanket; the self-absorption of Schroeder the musician; the teasing of his school mates; and the behavior of Snoopy, the flop-eared beagle with the wild imagination and the doghouse equipped with a Van Gogh, who sees himself as a World War I Flying Ace trying to shoot down the Red Baron when he is not running a "Beagle Scout" troop consisting of the bird Woodstock and his friends.

Charlie Brown's inability to cope with the constant, predictable disappointments in life, the failure and renewal of trust (typified by Lucy's tricking him every time he tries to kick the football), his touching efforts to accept what happens as deserved, all were traits shared in a lesser degree by his companions. Even crabby Lucy cannot interest Schroeder or understand baseball; Linus puzzled over life's mysteries and the refusal of the "Great Pumpkin" to show up on Halloween. The quirks and defects of humanity in general were reflected by Schulz' gentle humor, which constituted the appeal of the cartoon to the public, as it pinpointed our own adult weaknesses in a diminished and entertaining form, with a dash of pathos.

Part of the pleasure of "Peanuts" was the readers' expectation fulfilled, as the build-up to the penultimate frame reached the let-down of the final. "I realize … I am not alone … I have friends!" says Charlie Brown, momentarily reassured by "psychiatrist" Lucy. "Name one!" retorts Lucy, returning to her usual role.

Some writers find a moral and religious gospel to be drawn from Charlie Brown's dilemmas. Schulz maintained that he was more preoccupied by getting the strip on the drawing board. However, even to the casual reader "Peanuts" offered lessons to be learned. Schulz employed everyday humor, even slapstick, to make a point, but usually it was the intellectual comment that carries the charge, even if it was only "Good Grief!" Grief was the human condition, but it was good when it taught us something about ourselves and was lightened by laughter.

Schulz was twice married, to Joyce Halverson in 1949 (divorced 1972) and to Jean Clyde in 1973. He had five children by his first marriage: Meredith, Charles Monroe, Craig, Amy, and Jill. He was an avid hockey player, had a passion for golf, and enjoyed tennis.

Charles Schulz and the "Peanuts" characters remained a mainstay in the late 1990s. Schulz's work was beloved by the masses. He has had two retrospectives dedicated to his work within the past 15 years. The first was in 1985 at the Oakland Museum in Oakland, California and the second occurred in 1990 at the Louvre's Museum of Decorative Art in Paris. As of the late 1990s the syndicated cartoon strip of the "Peanuts" ran in over 2000 newspapers throughout the world on a daily basis.

The most complete biography was Rheta Grimsley Johnson, Good Grief: the Story of Charles M. Schulz (1989). The Funnies, An American Idiom, edited by David Manning White and Robert H. Abel (Part V, 1963), contained interesting comment placing Schulz in the context of American cartoonists. The Gospel According to Peanuts (1964) by Robert L. Short pointed out the similarity between "Peanuts" and many passages of the Bible. Charlie Brown & Charlie Schulz (1970) by Lee Mendelson with Charles M. Schulz presented useful comments but is somewhat dated. America's Great Comic-Strip Artists (Part 16, 1989), edited by Richard Marschall, provided up-to-date commentary on Schulz and other cartoonists and some comparison.