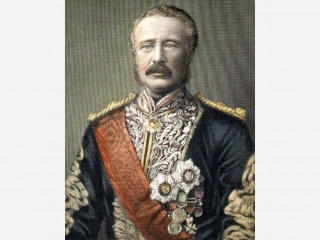

Charles George Gordon biography

Date of birth : 1833-01-28

Date of death : 1885-01-26

Birthplace : Woolwich, London

Nationality : British

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2011-02-07

Credited as : Soldier, adventurer and popular hero,

The English soldier, adventurer, and popular hero Charles George Gordon) was known as "Chinese" Gordon. He was killed at the fall of Khartoum.

Born at Woolwich on Jan. 28, 1833, Charles George Gordon was the son of a lieutenant general. He attended Taunton School and entered the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich in 1848, gaining his commission in the Royal Engineers in 1852.

At the end of 1855, during the Crimean War, Gordon was ordered to the Crimea. He was wounded there and then worked on the demolition of Sevastopol harbor. From May 1856 he was engaged in quasi-political work helping to delimit the frontiers of Bessarabia and Armenia. In 1860 Gordon joined the British forces operating with the French against China and was at the capture of Peking, spending the next 2 years fighting in southern China.

In 1863 Gordon took command of the small Chinese army in Sinkiang, which was officered by Europeans and which had been raised to suppress the Taiping Rebellion. At first Gordon quarreled with the Chinese authorities over the execution of rebels, but he returned to his post at the end of 1863, and by April 1864 the Taiping Rebellion was crushed. Gordon's exploits and his refusal to accept money presents offered by the Chinese emperor made him a popular hero in England from this time forward.

This heroic impression was reinforced during the years from 1865 to 1871, when Gordon served quietly in home army duties as commander of the Royal Engineers at Gravesend, supervising the Thames forts, for he spent much of his free time in social work, interesting himself in hospitals and schools for poor children and even taking destitute boys into his home.

In 1871 and 1872 Gordon was sent to Turkey to work on the International Danube Commission. In Constantinople he met Nubar Pasha, the Egyptian politician, and this led to his acceptance of an offer to succeed Sir Samuel Baker as governor of the Equatorial Provinces of the Sudan. Characteristically Gordon requested the salary of £10,000 be cut and accepted £2,000. Gordon's vigorous opposition to slave trading led to a quarrel with the Egyptian governor general of the Sudan, and Gordon resigned in 1876, but in January 1877 Gordon returned as governor general of the Sudan and Darfur and Equatoria, the other Egyptian provinces on the Red Sea. For the next 2 years he spent his time fighting in Darfur, suppressing rebellions elsewhere, and failing to secure agreement with Ethiopia on frontiers. When the British and French deposed Khedive Ismail, Gordon resigned at the end of 1879.

In April 1880 Gordon accompanied Lord Ripon, the new viceroy of India, as his private secretary but quickly resigned and spent the remainder of the year in China. During 1881 and 1882 he worked with the Royal Engineers in Mauritius and was in command of the British troops there from January 1882. In May he assumed command of the forces in Cape Colony but quarreled with the Cape government over its handling of the Basuto and left in October 1882, visiting Palestine the next year.

At the end of 1883 Gordon was approached by King Leopold II of the Belgians, who wished to employ him to take charge of plans to create the Congo Free State, from what was at that time ostensibly a philanthropic organization for "civilizing" the Congo Basin. In January 1884 Gordon accepted the offer, but the British War Office refused to sanction the appointment, and Leopold eventually chose H. M. Stanley for the post.

Gordon had intended to defy the War Office and resign his commission in the army. He was actually enroute for Brussels and the Congo when he was recalled by telegram to meet the British Cabinet, which persuaded him to accept the task of returning to the Sudan to withdraw the British and Egyptian troops there who were threatened by the successful revolt of the Mahdi. At the same time he was told to leave behind an organized government, so that his instructions were unclear.

By temperament Gordon was hardly the man to preside over the Sudan's abandonment (which the British government wanted so as to cut Egyptian expenditures). Arriving in Khartoum in February 1884, Gordon proceeded to proclaim the Sudan's independence, open communications with the Red Sea, demand Turkish troops to assist him, and request the presence of Zobeir Pasha, a notorious slave dealer, to form an alternative leadership to the Mahdi. Meanwhile Gordon made little move to withdraw, and the British and Egyptian governments did nothing to reinforce him. In March 1884 the Mahdists began their attack on Khartoum, and Gordon sent telegrams bitterly denouncing the government for neglect, until communications were cut off in April.

There followed a 10-month siege of Khartoum, during which William Gladstone's Liberal government resisted a growing popular clamor for Gordon's relief. In August 1884 money was voted for relief "should it become necessary," and Lord Wolseley was put in command of a force which left, after many delays, in September. But the expedition was too late; Khartoum fell to the Mahdi's army on Jan. 26, 1885, and Gordon was killed. The news reached England in February, and Friday, March 13, was officially declared a national day of mourning in Britain.

Gordon's death stirred a popular movement of indignation against Gladstone's Liberal government, which has been seen as one of the first stirring of popular "imperialism" in Britain and contributed to the collapse of the Liberals in 1885.

Gordon's own Journal, which he kept at Khartoum during the Mahdist siege, was edited by Lord Elton (1961), who also wrote a biography, Gordon of Khartoum: The Life of General Charles George Gordon (1954). Bernard M. Allen, Gordon and the Sudan (1931), is useful. The most recent treatment of Gordon's last months is John Marlowe, Mission to Khartoum: The Apotheosis of General Gordon (1969).