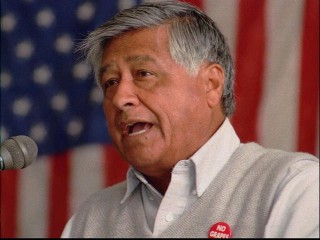

Cesar Chavez biography

Date of birth : 1927-03-31

Date of death : 1993-04-22

Birthplace : Yuma, Arizona, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-07-16

Credited as : Labor leader and former, ,

42 votes so far

"The schools treated you like you didn't exist. Their indifference was incredible."

Born March 31, 1927, near Yuma, Arizona, the second child of Librado and Juana Chavez, Cesar (Estrada) Chavez is president of the United Farm Workers of America (UFW) and a leading spokesperson for the rights of migrant workers.

In the spring of 1965, south of Delano, California, Filipino grape pickers of the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee (AWOC) went out on strike for higher pay. When the workers and the strike came north to Delano, Cesar Chavez and his National Farm Workers Association (NFWA) voted to join the strike to protest the conditions of migrant farm workers in California. The publicity generated by this strike brought widespread attention to the plight of migrant workers and thrust soft-spoken Cesar Chavez into the national spotlight as the leading spokesperson for "La Causa"--the term which came to signify both the strike of the grape pickers and the larger struggle of migrant workers everywhere.

Cesar Chavez grew up knowing well the plight of migrant workers in the United States. Chavez spent the first ten years of his life on a ranch run by his parents; however, when the Depression came, the county sheriff served the family papers and kicked them off their land. Penniless, the family moved to California in search of work, along with thousands of other people. There, they began to experience the hardships that face migrant workers. They first worked in the Imperial Valley tying carrots for a total daily pay of one to two dollars. They then went to the vegetable fields of Oxnard, and then the grape vineyards near Fresno, where they worked for weeks on a promise of pay--only to have the contractor disappear one day, leaving the family destitute. Chavez has said that the worst work in those days was thinning crops in the fields with short-handled hoes--bent over all day--for eight to twelve cents an hour. Winters were especially difficult for the family. "[The] winter of '38," he recalls, "I had to walk to school barefoot through the mud, we were so poor." After school, Chavez would fish in the canals and cut wild mustard greens to help his family survive.

As the migrant lifestyle began to settle in for the Chavez family, so did feelings of prejudice and rejection--living, for example, in segregated areas where "White Trade Only" signs were the norm. Discrimination against migrant farm workers also carried over into schools. By the time he dropped out of schools in the eight grade, Cesar had attended thirty to forty different schools. Sometimes students had to write "I won't speak Spanish" three hundred times on the blackboard. Describing the poor treatment of migrant children, Cesar recalls: "The schools treated you like you didn't exist. Their indifference was incredible." As a teenager, he began to rebel. Chavez rejected Mexican music, medicine, styles of dress, and some aspects of the Catholic Church. In 1943, at the age of sixteen, Cesar went to a segregated movie theater in Delano and sat in the "whites only" section. When the police came they pried his hands off the seat and dragged him to the police station. The anger, humiliation, and powerless from this incident made a deep impression on Chavez.

Chavez began his involvement in the fight for migrant rights during the late 1940s after he returned from Navy service in World War II. In the autumn of 1947, Cesar began working for the grape harvest in Delano, where workers had gone on strike demanding recognition of their farm labor union. The local sheriff and the U.S. Immigration Service intimidated the workers by raiding their camp nineteen times looking for illegal aliens. Chavez's first real taste of farm strikes, however, came in 1949 when cotton growers tried to reduce the wages of workers. Through his participation in the strike was small, and the workers went back to the fields, Cesar sensed the lack of leadership and disorganization in the strike and decided that something needed to be done about it.

In 1951 Chavez met Fred Ross, a community labor organizer, from whom he would learn the art of organizing. Hired by Ross and the Community Services Organization (CSO), Cesar first worked as an organizer in Oakland, California, and the poor urban centers of the East San Francisco Bay area. Following that experience, he returned to the rural barrios to organize farm workers and the poor, registering them to vote. In 1958, Chavez became director of the CSO, but resigned in 1962 because he felt the group was not doing enough for poor farm workers. He moved his family back to Delano and, with the help of his wife Helen, began organizing the National Farm Workers Association.

By the time of the 1965 Delano grape strike, Chavez's group was well organized and prepared. Chavez and AFL-CIO organizer Larry Itliang held the striking workers together until they finally won the strike and the growers agreed to a contract. In 1966, the NFWA merged with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee of the AFL-CIO to become the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee (UFWOC). By 1972, UFWOC was a legitimate union within the AFL-CIO, with 147 contracts covering 50,000 workers on farms in California, Arizona, and Florida. Now under the name of the United Farm Workers of America, Chavez's group numbers more than 100,000.

The work of Cesar Chavez on behalf of migrant farm workers has continued unabated to this day. One of the dramatic tactics he has adopted, in order to bring attention to the plight of workers, is the hunger strike. In 1968, Chavez fasted for twenty-five days and, in 1972, for twenty-four days. In 1988, Chavez did a thirty-six day fast in Delano to dramatize the UFWA's four-year boycott against California grape growers, protesting the reckless use of pesticides. It was one of Chavez's most publicized actions since "La Causa" twenty-three years earlier. By the time Chavez was persuaded to end his fast, he had lost thirty-three pounds. The fast for "La Causa" was continued, however, by Jesse Jackson and others. Asked about personally harmful actions such as hunger strikes, Chavez summed up the struggle for "La Causa" by saying: "It is not a fast unless you suffer."

August 18, 2005: Chavez had a high school in Stockton, California, dedicated in his name. His relatives did not attend the ceremony because they did not want to cross a picket line of teachers and janitors.