Catherine II biography

Date of birth : 1729-04-21

Date of death : 1796-11-06

Birthplace : Stettin, Prussia

Nationality : Russian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-04-08

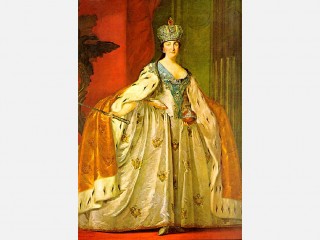

Credited as : Empress of Russia , Catherine the Great, House of Romanov

0 votes so far

Catherine II was born Sophia Augusta Frederica in the German city of Stettin, Prussia (now Szczecin, Poland), on April 21, 1729. She was the daughter of Prince Christian August of Anhalt-Zerbst and Princess Johanna Elizabeth of Holstein-Gottorp. Catherine's parents, who had been hoping for a son, did not show a great deal of affection toward their daughter. As a child, Catherine was close to her governess Babette, who Catherine described as, "the kind of governess every child should have." Catherine's education emphasized the subjects considered proper for one of her class: religion (Lutheranism), history, French, German, and music.

When Catherine was fifteen, she went to Russia at the invitation of Empress Elizabeth to meet the heir to the throne, the Grand Duke Peter (1728–1762), an immature and disagreeable youth of sixteen. Soon after Catherine converted to the Russian Orthodox faith, she and the young Grand Duke were married in 1745.

Catherine, although not descended from any previous Russian emperor, succeeded her husband as Empress Regnant. She followed the precedent established when Catherine I (born in the lower classes in the Swedish East Baltic territories) succeeded her husband Peter I in 1725.

Legitimists debate Catherine's technical status: seeing her as a Regent or as a usurper, tolerable only during the minority of her son, Grand Duke Paul. In the 1770s a group of nobles connected with Paul (Nikita Panin and others) contemplated the possibility of a new coup to depose Catherine and transfer the crown to Paul, whose power they envisaged restricting in a kind of constitutional monarchy. However, nothing came of this, and Catherine reigned until her death.

The marriage turned out to be an unhappy one in which there was little evidence of love or even affection. Peter was soon unfaithful to Catherine, and after a time she became unfaithful to him. Whether Peter was the father of Paul and Anna, the two children recorded as their offspring, remains a question.

However, her loveless marriage did not overshadow her intellectual and political interests. A sharp-witted and cultured young woman, she read widely, particularly in French. She liked novels, plays, and verse but was particularly interested in the writings of the major figures of the French Enlightenment (a period of cultural and idealistic transformation in France), such as Diderot (1713–1784), Voltaire (1694–1778), and Montesquieu (1689–1755).

Rise to power

Catherine was ambitious as well as intelligent and looked forward to the time she would rule Russia. Unlike her husband, the German-born Catherine took care to demonstrate her dedication to Russia and the Russian Orthodox (an independent branch of the Christian faith) faith. This loyalty, she thought, would earn her a rightful place on the throne and win support of the Russian people.

When Empress Elizabeth died on December 25, 1761, Peter was proclaimed Emperor Peter III, and Catherine became empress. Only a few months after coming to the throne, Peter had created many enemies within the government, the military, and the church. Soon there was a plot to overthrow him, place his seven-year-old son Paul on the throne, and name Catherine as regent (temporary ruler) until the boy was old enough to rule on his own. But those involved in the plot had underestimated Catherine's ambition. They thought that by getting rid of Peter, Catherine would become more of a background figure. She aimed for a more powerful role for herself, however. On June 28, 1762, with the aid of her lover Gregory Orlov, she rallied the troops of St. Petersburg to her support and declared herself Catherine II, the sole ruler of Russia. She had Peter arrested and required him to abdicate, or step down from, power. Shortly after his arrest he was killed in a brawl with his captors.

Catherine had ambitious plans regarding both domestic and foreign affairs. But during the first years of her reign her attention was directed toward securing her position. She knew that a number of influential persons considered her a usurper, or someone who seized another's power illegally. They viewed her son, Paul, as the rightful ruler. Her reaction to this situation was to take every opportunity to win favor among the nobility and the military. At the same time she struck sharply at those who sought to replace her with Paul.

As for general policy, Catherine understood that Russia needed an extended period of peace in order for her to concentrate on domestic (homeland) affairs. This peace could only be gained through cautious foreign policy. The able Count Nikita Panin (1718–1783), whom she placed in charge of foreign affairs, was well chosen to carry out such a policy.

By 1764 Catherine felt secure enough to begin work on reform, or improving social conditions. Catherine's rule was greatly influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, and it was in the spirit of the Enlightenment that Catherine undertook her first major reform. Russia's legal system was based on an old and inefficient Code of Laws, dating from 1649. Catherine's proposal, "The Instruction," was widely distributed in Europe and caused a sensation because it called for a legal system far in advance of the times. It proposed a system providing equal protection under law for all persons. It also emphasized prevention of criminal acts rather than harsh punishment for them.

In June 1767 the Empress created the Legislative Commission to revise the old laws in accordance with the "Instruction." Catherine had great hopes about what the commission might accomplish, but it made little progress, and Catherine suspended the meetings at the end of 1768.

Foreign affairs began to demand Catherine's attention. She had sent troops to help her former lover, Polish king Stanislaw (1677–1766), suppress a revolt that aimed at reducing Russia's influence in Poland. Soon Turkey and Austria joined in by supporting the revolution in Poland. Two years later, after lengthy negotiations, Catherine concluded peace talks with Turkey. From this Russia received its first foothold on the Black Sea coast. Russian merchant ships were allowed the right of sailing on the Black Sea and through the Dardanelles, a key waterway in Europe.

Even before the peace talks ended, Catherine had to concern herself with a revolt led by the Cossack Yemelyan Pugachev (1726–1775). The rebel leader claimed that reports of Peter III's death were false and that he was Peter III. Soon tens of thousands were following him, and the uprising was within threatening range of Moscow. Pugachev's defeat required several major expeditions by the imperial forces. A feeling of security returned to the government only after his capture late in 1774.

Much of Catherine's fame rests on what she accomplished during the dozen years following the Pugachev uprising. Here she directed her time and talent to domestic affairs, particularly those concerned with the way the government functioned. Catherine was also concerned with expanding the country's educational system. In 1786 she adopted a plan that would create a large-scale educational system. Unfortunately, she was unable to carry out the entire plan, but she did add to the number of the country's elementary and secondary schools. Some of the remaining parts of her plan were carried out after her death.

The arts and sciences also received much attention during Catherine's reign. Not only because she believed them to be important in themselves, but also because she saw them as a means by which Russia could earn a reputation as a center of civilization. Under her direction St. Petersburg was turned into one of the world's most dazzling capitals. Theater, music, and painting flourished with her encouragement.

As she grew older, Catherine became greatly troubled because her heir, Paul, was becoming mentally unstable and she doubted his ability to rule. She considered naming Paul's oldest son, Alexander, as her successor. Before she was able to alter her original arrangement, however, she died of a stroke on November 6, 1796. While her legacy is open to debate, there is no doubt that Catherine was a key figure in developing Russia into a modern civilization.