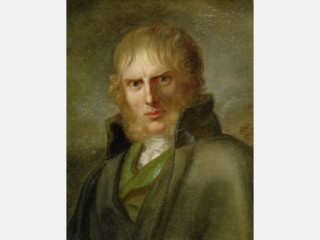

Caspar David Friedrich biography

Date of birth : 1774-09-05

Date of death : 1840-05-07

Birthplace : Greifswald, German

Nationality : German

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-02-01

Credited as : Artist painter, ,

Caspar David Friedrich, one of the major artists of German romanticism, revived landscape painting in Germany, depicting through nature his own melancholy moods, pantheistic beliefs, and nationalistic feelings.

Born on Sept. 5, 1774, in Greifswald, Caspar David Friedrich was the son of a soap manufacturer. His mother died when he was 7; and when he was 13, his favorite brother died while the two boys were ice-skating, for which Caspar David suffered a lifelong sense of guilt. The painter's familiarity with death and his melancholy disposition were further affirmed by a suicide attempt.

Friedrich began studying drawing in 1788; in 1794 he entered the art academy in Copenhagen, one of the most liberal in Europe, notably in its unusual emphasis on drawing from nature rather than from older art. His teachers were masters of Danish neoclassicism, but they also transmitted the concepts of early English romanticism, notably Henry Fuseli's theories, before Friedrich left for Dresden in 1798.

Friedrich's early landscapes and engravings are much like his teachers' works, but constant sketching after nature released him from neoclassic formulations, and a careful realistic rendering asserted itself in vast, spacious landscapes at times populated by small isolated figures or heroic ruins. By 1806 he had developed an independent formal and iconological vocabulary.

Friedrich's reputation grew rapidly; he found patrons among Saxony's nobility and received the Prize of the Weimar Friends of Art. He became acquainted with the major writers of German romanticism and with the painters Phillip Otto Runge, Johan Christian Dahl, and Carl Gustav Carus. In 1808 the classicist critic F. W. B. von Ramdohr attacked Friedrich's painting Cross in the Mountains (also known as the Tetschen Altarpiece), demanding whether "it is a good idea to use landscape allegorically to represent a religious concept or even to arouse a sense of reverence." After criticizing the painting, depicting a crucifix on a mountain illuminated by the setting sun, Ramdohr concluded that a depiction of nature cannot properly be symbolical or allegorical, that "it is the greatest arrogance when landscape painting seeks to worm its way into the churches and crawl onto the altars." Several of Friedrich's friends answered these criticisms in detail, thereby causing a major argument that served ultimately to increase the artist's fame.

Friedrich himself interpreted the painting as representing man's continuous faith and hope in the person of Jesus Christ despite the decline of formalized religion. Whether populated by Christian symbols or not, Friedrich's landscapes all possess a spiritual quality, and such religious meanings reflect his own mystical convictions. Contact with the romantic writers had convinced him that "art must have its source in man's inner being; yet, it must be dependent on a moral or religious value." Among his aphorisms on art, he wrote: "The noble man (artist) recognizes God in everything…. Shut your corporeal eye so that you first see your picture with your spiritual eye. Then bring to light that which you saw in darkness so that it may reflect on others from the exterior to their spiritual interior." Like the romantic writers, he saw art as the mediator between man and the mystical sources of nature. His own time Friedrich viewed as being on the periphery of all religions, founded on the ruins of the temples of the past and building for a future of clarity and nondogmatic religious truth.

Contemporary political events formed the other major content of Friedrich's work. The Napoleonic Wars aroused in him a fierce hatred of France and an intense love of Germany. He expressed his patriotic support of the German liberation movements in mountain scenes depicting lost French soldiers or monuments to German freedom fighters. And his disappointment in the antidemocratic Prussian restoration after the wars was symbolized in a painting of an ice-encrusted ship named Hope (1822).

In 1816 Friedrich became a member of the Dresden Academy, which gave him a steady income and allowed him to marry in 1818. In 1820 the Russian czarevitch purchased several paintings from him, but Friedrich's popularity began to decline because of his political attitudes and increasing official attacks on his art. His mental and physical health steadily deteriorated. In 1837 a serious stroke terminated his career. He died on May 7, 1840, forgotten by all but a small circle of friends. His subjective, emotional art was rediscovered early in the 20th century, when German expressionism sought similar effects through more radical means.

A surprisingly balanced pamphlet on Friedrich was published by the German Library of Information, Caspar David Friedrich: His Life and Work (1940). More recent is Leopold D. Ettlinger, Caspar David Friedrich (1967). See also Marcel Brion, Art of the Romantic Era (trans. 1966).