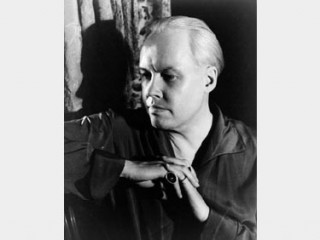

Carl Van Vechten biography

Date of birth : 1880-06-17

Date of death : 1964-12-21

Birthplace : Cedar Rapids, Iowa, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-27

Credited as : Author and photographer, The Blind Bow-Boy,

American author and photographer Carl Van Vechten was a champion of modern music and dance in the early years of the twentieth century, and went on to enjoy critical acclaim for his witty novels that chronicled a charmed set in 1920s New York and Paris. Van Vechten, however, may be best remembered for his interest in the creative output of African-Americans: through his support for its writers and performers, his financial assistance, and enthusiastic, insightful essays for mainstream publications, he served as an unofficial publicist for the cultural movement that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance.

Carl Van Vechten was born in 1880 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, into a prosperous and politically liberal family. He was tall and awkward in stature, and gifted with an above-average intelligence. Van Vechten stood out from his Midwestern peers in several ways and would later reflect upon Cedar Rapids and its mores with not a small amount of disdain. At the age of 19 he left Iowa for the more cosmopolitan world of Chicago, where he attended the prestigious University of Chicago. He enjoyed the standard fare of plays, galleries, and concerts that the city offered, but also became fascinated with the city's thriving African-American culture; he sometimes accompanied the housekeeper of his fraternity to chapel services, where Van Vechten-an accomplished musician-played the piano.

After graduation in 1903, loathe to return to Cedar Rapids and a post at his uncle's bank, Van Vechten obtained a job at the Chicago American, part of the Hearst newspaper chain. After a year, he was fired for writing a particularly barbed gossip column, and eventually moved to New York City in the spring of 1906. In an apartment house on West 39th Street that was also home to the more renowned writer Sinclair Lewis, he continued writing the short stories and essays he had first attempted in college. He also partook of Manhattan's rich cultural offerings.

Early in 1907 Van Vechten convinced the editor of Broadway Magazine, Theodore Dreiser, to buy his article on a controversial new musical drama at the Metropolitan Opera House, Richard Strauss's Salome. Later that year, having lived on funds borrowed from his father until that point, Van Vechten obtained a permanent job as a staff reporter at the New York Times. He was soon made an assistant to their music critic, and covered noteworthy new productions and symphonies premiering on New York's stages.

Van Vechten's passion for opera led him to convince his father to loan him money so that he might experience European opera in its own setting. Furthermore, he planned to marry a friend from Cedar Rapids, Wellesley graduate and fellow cosmopolitan Anna Snyder. The pair were wed in London around 1907 and spent months traveling the Continent and enjoying its cultural treasures, though they were sometimes short on funds. The next year, after returning to New York, they again left the country when Van Vechten was sent to Paris as the New York Times correspondent there, where he wrote on such topics as the Wright Brothers experimental flights in France.

The Van Vechtens divorced around 1912. That same year, he met the actress Fania Marinoff when he was back living in New York and working for the New York Press as its drama critic. They were wed in 1914 but Snyder filed charges for back alimony and he spent four months in the Ludlow Street jail; the incident would later appear in one of his novels. His first book, Music after the Great War, appeared in 1915 as a result of a publishing contact he had made as a Times reporter. The work was a collection of essays on music and ballet, some previously published. It marked him as an influential champion of modern music and dance, both forms then gaining ground in Europe. Van Vechten's first work included essays on Igor Stravinsky and the Russian ballet, among other topics.

His second book, Music and Bad Manners, was also his first for the publishing house Alfred A. Knopf, with whom he would enjoy a long relationship. Over the next few years he continued to write on music and the theater for various publications, and during this time he also became acquainted with some prominent African-Americans, such as the writer and civil-rights personality Walter White. Van Vechten also wrote on seminal African-American works for the stage such as The Darktown Follies and Shuffle Along.

By 1920, Van Vechten's sixth and seventh titles appeared in print-Tiger in the House, about the domestic cat, one of his great loves, and the well-received In the Garrett, an erudite collection with essays on Oscar Hammerstein, the Yiddish theater, and the lack of a folk tradition in the American Midwest. His first novel, Peter Whiffle: His Life and Works, was published in 1922. The plot revolves around a young man and his adventures in Paris, and was clearly based on his own experiences. "This pseudo-biographical novel, " wrote Marvin Shaw in an essay in Gay & Lesbian Biography, "depicted the creation of a refined dilettante's temperament and wittily exposed the manners and morals of the author's era of elegant decadence."

Van Vechten followed with another novel, The Blind Bow-Boy, in 1923, but remained an enthusiastic supporter of the arts. His tastes expanded to include the cultural offerings of Harlem, home to Manhattan's thriving black middle class, and by 1924 he had met the African-American novelist and diplomat James Weldon Johnson. Through this luminary, one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Van Vechten met many other prominent names in the arts who would play important roles in the cultural movement that came to be known as the Harlem Renaissance. These included novelist Zora Neale Hurston, and poets Countee Cullen and Langston Hughes. It was through Van Vechten's intercession with Knopf on behalf of the latter that the groundbreaking collection of Hughes's verse, The Weary Blues, appeared in print in 1926.

Van Vechten became immersed in the Harlem Renaissance and its flowering of African-American culture. He wrote about its blues singers, such as Bessie Smith, in a series of articles for Vanity Fair beginning in 1925, and was also a backer for Paul Robeson's staging of African-American spirituals. Yet Van Vechten also led a profligate life-he could be a heavy drinker at times, and though married was known to enjoy the company of others. He would later suffer criticism for his championing of Harlem as a heady, intoxicating playground. It became a fashionable "thrill" for well-heeled white New Yorkers to venture into Harlem's integrated nightclubs to listen to the jazz or blues of performers such as Billie Holiday, or the racy shows of Josephine Baker.

The height of Van Vechten's celebrity came with the publication of his fifth novel, Nigger Heaven. The title, shocking by contemporary standards, aroused controversy in 1926 as well. The phrase reflected both Harlem itself at the time, in the African-American vernacular, as well as a term for the top tier of seats in a segregated theater. The novel offered a love-triangle plot, but served more to educate mainstream readers about life in a hidden quarter of America's most cosmopolitan city. Furthermore, it introduced readers to facets of black political and social life heretofore unexplored in literature. Van Vechten biographer Bruce Kellner, in an essay in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, termed the novel "a deliberate attempt to educate Van Vechten's already large white reading public, the novel presents Harlem as a complex society fractured and united by individual and social groups of diverse interests, talents, and values."

The work was also quite racy, and its author was plagued by charges of sensationalism. The volume sold well, but endured harsh criticism. James Weldon Johnson was virtually its only champion among the black intelligentsia: he reviewed it for Opportunity, and opined that Van Vechten "pays colored people the rare tribute of writing about them as people rather than puppets." Others viewed it with far less admiration. In The Crisis, W.E.B. Du Bois called it "neither truthful nor artistic, " and found fault with its depiction of Harlem solely as a playground for the fatuous and amoral. D. H. Lawrence, in an essay titled "Literature and Art: Nigger Heaven, " found it "the usual old bones of hot stuff, warmed up with all the fervour the author can command-which isn't much." Nevertheless, it was a commercial success, and enhanced Van Vechten's reputation as a patron of the Harlem Renaissance.

Van Vechten continued to author articles for Vanity Fair and other publications, and wrote rather unkindly about his travels in Hollywood in essays which formed the basis for the 1928 novel Spider Boy: A Scenario for a Moving Picture. His last work of fiction, Parties: Scenes from Contemporary New York Life, was started just a few days after the Wall Street crash of 1929, a calamitous event which served to sober up the heady decade. The volume is the only one of Van Vechten's works "to stand as a terrible indictment of the period, " wrote Kellner in Carl Van Vechten and the Irreverent Decades. "The others had laughed at the foibles of the whole drunken generation; this one wept." Parties was met with derision by critics. Yet Van Vechten had wearied of fiction and essays and began to explore another creative pursuit-portrait photography. By 1932 he had dedicated himself exclusively to this, and his portraits of many luminaries of the day, as well as up-and-coming performers such as Lena Horne, Alvin Ailey, and Harry Belafonte, remain incisive glimpses into the era.

Van Vechten was already in his fifties when he gave up writing, and enjoyed his final years as a philanthropist. He founded the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection of Negro Arts and Letters at Yale University, and willed his own archives to it; he also directed that any of posthumous royalties from his books be donated to its endowment fund. Also at Yale he established the Anna Marble Pollock Memorial Library of Books about Cats, dedicated to the wife of playwright Channing Pollock and one of his first friends in New York City. Van Vechten died in his sleep on December 21, 1964, and his ashes were scattered in Central Park's Shakespeare Gardens. Examples of Van Vechten's best photographic work were assembled and published in the 1978 volume Portraits: The Photography of Carl Van Vechten, and "Keep A-Inchin' Along": Selected Writings of Carl Van Vechten about Black Art and Letters, a collection of his work about African-American culture, was published in 1979.

Contemporary Literary Criticism, Volume 33, Gale, 1985.

Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 51: Afro-American Writers from the Harlem Renaissance to 1940, Gale, 1987.