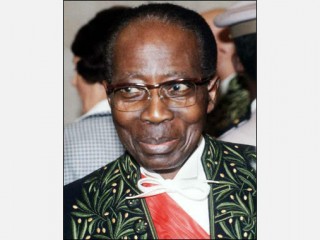

Camara Laye biography

Date of birth : 1928-01-01

Date of death : 1980-02-04

Birthplace : Kouroussa, Upper Guinea

Nationality : Guinean

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-26

Credited as : Writer and novelist, L'Enfant noir 1953, Prix Charles Veillon

Camara Laye was a Guinean writer. His novel L'Enfant noir established him as one of the most important novelists from French-speaking Africa.

Camara Laye was born in Kouroussa in Upper Guinea on January 1, 1928. According to Adele King in The Writings of Camara Laye, he was, "passionately concerned with preserving a record of traditional homeland." He let his narrative and his gently observed characters speak of the warmth, wholeness, and deep piety of pre-colonial African culture and of the growing sadness of his people as their culture changed under both the curse and the stimulus of French rule and influence.

Laye's family belonged to the Malinké people, who retained their ancestral animist religion, despite the region's overall conversion to Islam several centuries ago. His father, Camara Komady, was a blacksmith and goldsmith and a descendent of the Camara clan, which traced its genealogy back to the thirteenth century. His mother, Dâman Sadan, also came from a family of blacksmiths. Although Camara was his family name, he published his work as Camara Laye, retaining the format used in Guinean schools. Laye's early childhood years were strongly traditional and full of happiness; Sonia Lee in Camara Laye wrote that, "For Laye, Africa remained forever the Africa of his youth, and he was always to look upon her with the eyes of the heart."

First studying in Koranic and French-run schools, Laye went on to study technical subjects at the Ecole Poiret in Conakry. Laye was fortunate that his father allowed him to pursue his education rather than assist him at his forge. In 1947 he won a scholarship to France, where he studied motor engineering at Argenteuil and earned his Automobile Mechanic's Certificate. He decided to remain in Paris after his scholarship had finished and continue his technical education; although he loved literature, he had not yet developed any pretensions of becoming a writer. Laye then attended school at the Conservatoire des Arts et Metiers and the Ecole Technique d'Aeonautique et de Construction Automobile, where he received a diploma in engineering. He supported himself as a porter in Les Halles and at the Simca automobile plant.

However, Laye believed that the sacrifices he made by leaving his home, warranted more, "It was not, in my opinion, worth the trouble to leave Africa only to become a mechanic. It was too simple a job." Feeling lonely for his homeland, Laye began writing down warm memories of his childhood in Guinea, which became the roots of his first novel.

L'Enfant noir (1953; Dark Child) is primarily a recounting of Laye's own voyage from childhood, when he played near his father's goldsmith forge, to gifted young manhood, when he departed for France. The book wins its audience through its tender but unsentimental treatment of the older African life and the dignity and beauty of that nostalgically lamented past. Laye expresses his deep anxiety at leaving his homeland, writing, "It was a terrible parting! I do not like to think of it. I can still hear my mother wailing. It was as if I was being torn apart." However, this separation enhanced his appreciation for his home and his culture. Shortly before the publication of his first novel, he brought Marie Lorifo, whom he had known from Conakry, to Paris and married her. L'Enfant noir received critical acclaim and won the Prix Charles Veillon in February of 1954; the novel was recognized as one of the most important pieces of contemporary prose from French-speaking Africa.

Laye's second novel, Le Regard du roi (1954; The Radiance of the King), presents the wandering Ishmael of a starveling Frenchman adrift in Africa and forced to work out through suffering a new destiny for himself. Clarence, guided by two jostling, derisive, but still solicitous boys, finds a home of sorts as a stud for a tired master of a large harem. Beginning his trek in search of a wonderfully wise and rich king, Clarence enters the whirlpool of sloth, of lust, of despair, until one day the King arrives and accepts in his open arms the bedraggled but earnest man, no longer full of the unconscious arrogance of the white man. Widely considered Laye's masterpiece, Le Regard du roi firmly established Laye's reputation as a quality writer.

Laye and his wife returned to Guinea in 1956. He worked in several positions in West Africa, including teaching French in Accra, Ghana. After Guinea attained its independence in September of 1958, Laye became Guinea's ambassador to Ghana and played a key role in procuring aid for his country. He also spent a short time as a diplomat in Liberia; later, he returned to Guinea and held a series of prominent positions including director of the Department of Economic Agreements at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and associate director of the National Institute of Research and Documentation.

While working for the government, Laye continued to write, completing plays for radio and collecting some oral literature of the Manding. His popularity in West Africa grew. He received critical praise in the first issue of Black Orpheus in 1957 and was included in Gerald Moore's Seven African Writers (1962).

As Guinea's political situation deteriorated, Laye voiced his concern. He soon fell into disfavor and often was close to being under house arrest. In 1965 he fled with his family to Dakar in Senegal. Torn from his beloved homeland, he would never be able to return. Because of his intense distaste for the authoritative regime of President Seekou Toure, Laye's third novel, Dramouss (1966; A Dream of Africa), is a bitter, even savage, denunciation of a regime he envisioned as a nightmare of a giant astride the wounded Guinea in which he had lived during the 1960s.

Life for Laye and his family in Senegal was not easy. He worked as a research fellow at the Institut Fondamental d'Afrique Noire (IFAN), collecting and editing the folktales and songs of the Malinke people, but his income was significantly lower than the salary he had received from the Guinean government. In 1970, Laye's wife was arrested at the airport in Guinea after receiving a letter from her sick father urging her to visit. Laye was left to raise their seven children, the youngest of whom was only several months old when she left. In 1971 Laye completed a novel entitled L'Exile, but deferred its publication because of its political sensitivity and his wife's confinement in Guinea. During his wife's imprisonment, Laye married a second wife—a custom among some Muslim denominations—and had another two children. After his first wife was released in 1977, she returned to Dakar, but was unable to accept Laye's additional wife. As a result, the couple divorced.

In 1975 Laye became acutely ill with a kidney condition that had first troubled him back in 1965, but he could not afford the treatment in Europe that he needed. Reine Carducci, wife of the Italian UNESCO ambassador to Senegal and an admirer of Laye's work, became conscious of Laye's plight and championed an appeal for financial support. Felix Houphouët-Boigny, president of the Ivory Coast, made the largest contribution; Laye later wrote his biography and expressed his admiration for the leader. Laye received the necessary medical care in Paris and returned periodically for further treatment.

In 1971 Laye began writing Le Maitre de la parole (1978). Though eschewing collaboration with the many exiled enemies of Toure, Laye in an interview did not hide his debt to Kafka and the surrealists and his intention to mingle fiction and reality into a new and greater truth in the effort to express his own outrage at what had happened to his homeland. An honest artist and a sensitive participant in the pains of a postcolonial world, Laye produced works that speak about the clamor and that are more poignant because of their intense dream-like style. Eventually, Laye's ill heath caught up with him and he died on February 4, 1980, in Dakar, where he is buried.

Information on the life and work of Laye is in Gerald Moore, Seven African Writers (1962); Claude Wauthier, The Literature and Thought of Modern Africa (1964; trans. 1966); Judith Illsley Gleason, This Africa: Novels by West Africans in English and French (1965); Ulli Beier, ed., Introduction to African Literature (1967); A. C. Brench, The Novelists' Inheritance in French Africa (1967); and Wilfred Cartey, Whispers from a Continent: The Literature of Contemporary Black Africa (1969); the chapter by Jeanette Macaulay in Cosmo Pieterse and Donald Munro, eds., Protest and Conflict in African Literature (1969); Adele King, The Writings of Camara Laye, Heinemann (1980); and Sonia Lee, Camara Laye, Twayne Publishers (1984).