Bukka White biography

Date of birth : 1909-11-12

Date of death : 1977-02-26

Birthplace : Houston, Mississippi, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-03-13

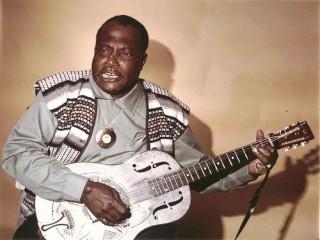

Credited as : blues guitarist, Singer, Blues musician

1 votes so far

Bukka White's classic Mississippi blues music was simple, intense, and above all, personal. Accompanying himself ferociously with a National steel-bodied guitar played slide-style with a short metal tube, he sang in unvarnished terms about his own life experiences, and he made what are generally considered his greatest recordings after serving two years in the notorious Parchman Farm prison. Forgotten for many years, White enjoyed a career revival during the folk music boom of the 1960s.

Booker T. Washington White was born near Houston, Mississippi, probably on November 12, 1906. He was one of seven children. White was raised on a sharecropper's farm by his maternal grandfather, the Rev. Punk Davisson. His father, John White, was a railroad fireman and part-time musician; when he was in town, he taught White to play the guitar and took him and his other children to the local Baptist church. Houston was in Chickasaw County, in north-central Mississippi, east of the Mississippi River delta. When White moved to Grenada, Mississippi, to work on an uncle's farm around 1919 (the chronology of his early life is hazy), he found himself in the midst of the vital delta music tradition.

White heard the greatest of the early bluesmen, Charley Patton, and was inspired by him, although his musical style was his own. As he worked long hours in the fields, "none of the other boys, they didn't have any idea what I was thinking about," he said in an interview quoted by blues historian Samuel Charters. He learned to play the piano as well as guitar, and he began to perform wherever he had the chance---in delta juke joints and honky tonks, at dances, in pool rooms and bars up the river in Memphis and St. Louis, or on the streets. In St. Louis, working in a roadhouse, White was befriended by an older musician named Johnny Thomas, who gave him some lessons on guitar and piano. Pay for White's performances was scanty, if it was given at all; often, he was quoted as saying by F. Jack Hurley and David Evans, "I played for a rabbit sandwich, piece of egg pie or tater pie and all the water I could drink." In 1925 White married and was given a new Stella guitar by his father as a present. Tragically, his wife died a painful death three years later after suffering a ruptured appendix.

Performing in Memphis, White met Ralph Lembo, a white Mississippi furniture dealer who served as an agent for the Victor label, and he enthusiastically stepped into Victor's Memphis studio to record 14 sides in 1930. Several of them were gospel pieces; one, "I Am in the Heavenly Way," was billed as a "Sermon Sung for You by Washington White, 'The Singing Preacher,' with Guitars and Women Singers." With the Depression underway, Victor released only four of White's recordings. After wandering the country as a freight-train-riding hobo for a time, White returned to Mississippi and married again, settling near Aberdeen and performing occasionally with his wife's uncle, singer and harmonica player George "Bullet" Williams. Pitching for the Birmingham Black Cats of baseball's Negro Leagues, stepping into the ring as a boxer occasionally, and making moonshine liquor, he managed to eke out a living during extremely hard times.

The world of Mississippi's honky tonks was a violent one, and White, claiming self-defense, shot a man after being ambushed by a group on a dark road. Sentenced to two years at Parchman Farm on assault charges, White traveled to Chicago to record two sides for the Vocalion label before beginning his sentence in the fall of 1937. According to legend, which surrounds White even more thickly than it does many other early blues figures, he jumped bail and was re-arrested by a Mississippi sheriff in the recording studio. It is likelier that he benefited from the intervention of agent Lester Melrose, an industry figure who did much to help White's career in the Windy City. One of White's two 1937 recordings, "Shake 'em on Down," was a hit and became part of the repertoire of Chicago blues.

White's musical skills helped keep him off the prison's field and work gangs for the most part; he was allowed to organize a prison band that, he recalled, entertained the visiting governor of Mississippi. He recorded two songs for Library of Congress investigator Alan Lomax. Still, life at the prison was a harsh, isolating experience, and White had little to do but think about new songs as he watched other prisoners give in to loneliness and feelings of impending death, and suffered through those fears himself. White's music deepened, and as urban blues began to take on elements of good-time party music around 1940, he headed in an entirely different direction creatively.

After his release, White headed for Chicago with the idea of resuming his recording career. He wrote out lyrics to some famous blues songs like "Sittin' on Top of the World" and went to see Melrose, hoping to impress the agent with his preparation. But from Melrose's point of view there was more potential profit in copyrighting original songs, so he sent White to a hotel room with instructions to come up with new material. For White, who had brooded over his music for two years in prison, that was the perfect assignment.

Featuring light accompaniment from a musician named Washboard Sam, the 14 sides that White recorded in Melrose's South Side studio on March 7, 1940, released on the Vocalion and OKeh labels, are considered some of the very greatest classics of the blues. Melrose was the first person to realize the magnitude of White's achievement. "I never had a man, black or white, kiss me dead on the mouth before, but that's what he done," White was quoted as saying by Hurley and Evans. "He say, 'Lord man, you done 100 percent. I've been on this job 35 years and I never seen a man do what you done in two days.' He said, 'Just how the hell did you get it? Where did it come from?'" Several of White's 1940 sides, such as "When Can I Change My Clothes?," were stark representations of prison life, and others, such as "High Fever Blues" and "Fixin' to Die Blues," spoke of the bitter end to which the life of an African American in the South would often come. On just a few songs, such as "Bukka's Jitterbug Swing," White lightened the mood and showed off his intricate slide guitar style.

The renown these records deserved had to wait for many years; only modest numbers of his records were sold, and they are valuable collectors' items today. White returned to Memphis and took a job in a defense plant. His second marriage broke up. Though he occasionally performed with the older Memphis musician Frank Stokes after the war, his rural style was now of interest only to older listeners. Most of his musical energy was devoted to encouraging his cousin, a Mississippi musician and disc jockey named Riley King who went by the title "Blues Boy," soon shortened to "B.B." Through the 1950s, White worked quietly in Memphis and remained almost completely unknown in the musical world.

By the end of that decade, however, folk music enthusiasts and scholarly investigators were beginning to uncover the treasures of the country blues, and young, mostly white musicians soaked up their findings. The youthful Bob Dylan recorded White's "Fixin' to Die Blues" on his first LP in 1961, and rare copies of White's 78 rpm discs circulated among collectors. In 1963 two University of California students, John Fahey and Ed Denson, addressed a letter to "Booker T. Washington White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi." The letter found its way to White, who headed to the West Coast in the fall of that year. He performed for folklore students and played some gigs at one of the centers of the West Coast folk revival, the Ash Grove in Los Angeles.

White remained a resident of Memphis for the rest of his life, often sitting on a stool on Mosby Street that he called his office and negotiating the concert offers that now came in regularly. Several albums of White's music were released; Fahey and Denson issued Mississippi Blues: Bukka White on their Takoma label, capturing White's older material, and roots music collector Chris Strachwitz released two volumes of new White compositions, Sky Songs: Vols. 1 and 2, on the Arhoolie label. The title "Sky Songs" was White's own, meaning that he could just reach up and pull them out of the sky. In "1963 Ain't 1962 Blues," White reflected wryly on his newfound success.

Late in his life White became a figure known to music fans worldwide. He sang at the premier venue of the folk music movement, the Newport Folk Festival in Rhode Island. He appeared at the 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City and toured Europe several times, releasing two albums in Germany. Despite poor health in the 1970s, White continued to perform until shortly before his death in Memphis on February 26, 1977, from pancreatic cancer.