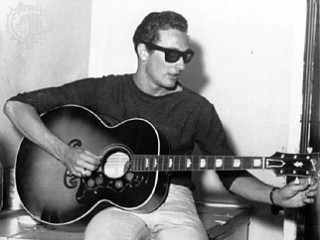

Buddy Holly biography

Date of birth : 1936-09-07

Date of death : 1959-02-03

Birthplace : Lubbock, Texas, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-24

Credited as : Rock and roll singer-songwriter, That'll Be the Day,

One of rock 'n' roll's founding fathers, Buddy Holly recorded a highly influential body of work before his untimely death. Holly's unique mix of pop melodicism, aggressive rhythmic drive, and imaginative arrangement ideas directly inspired the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and numerous other bands in the coming decades.

At age 22, a fatal plane crash made Buddy Holly into an instant rock 'n' roll legend. His string of hit records—including "That'll Be the Day," "Peggy Sue," "Oh Boy!," and "Rave On"—had made him a celebrity in America and beyond. What proved to be remarkable about Holly was that his stature increased with time, rather than fading as was typical with pop music idols. His distinctive mix of rock 'n' roll, country, and R & B served to inspire a generation of younger artists and remained vital for decades to come. In terms of both his creative output and his stage persona, Holly helped to broaden the range of possibilities within the rock 'n' roll idiom.

Holly was born Charles Hardin Holley in Lubbock, Texas on September 7, 1936. The youngest of three children, he was nicknamed "Buddy" by his mother, Ella Drake Holley. His father, Larry Holley, worked at various times as a cook, carpenter, tailor, and clothing salesman. Holly showed an early interest in music, winning a local talent contest at age five. By age 11, he had taken piano lessons and was beginning to learn guitar. During his high school years, he performed regularly on a Lubbock radio station, first with Jack Neal, then with Bob Montgomery as a partner. Eventually, a group evolved that included Holly and Montgomery on guitar and Don Guess on acoustic bass. The combo—known as Buddy and Bob and, later, the Rhythm Playboys—played country music, although Holly was beginning to take an interest in R & B and blues as well. In January of 1955 Holly saw Elvis Presley perform in Lubbock, inspiring him to play rock 'n' roll. By the time he graduated high school that same year, he was already a popular performer on the local dance and club scene.

Playing the country/rock hybrid dubbed "rockabilly," Holly and his group opened shows for Presley, Bill Haley, and other notable acts on tour in late 1955. After meeting talent scout Eddie Crandall, he signed a recording contract with Decca Records as a solo artist and, with Sonny Curtis replacing Montgomery on guitar, went to Nashville on January 26, 1956, to record four songs. Producing these sessions was Owen Bradley, later famous as the man behind the hits of Patsy Cline. After further touring on the country-music circuit, he recorded several more tunes, including "That'll Be the Day," a song co-written by Holly and newly recruited drummer Jerry Allison. None of the songs recorded for Decca attracted much attention, and he was released from his contract.

Undaunted, Holly took his band—now including rhythm guitarist Niki Sullivan and re-named the Crickets— to the Clovis, New Mexico, studio of producer Norman Petty, known for his work with rockabilly artist Buddy Knox. In February 1957 the Crickets recorded new versions of "That'll Be the Day," "Maybe Baby," and several other tunes. Petty was impressed by the young musician's talent and attitude. "I was amazed at the intensity and honesty and sincerity of [Buddy's] whole approach to music," Petty later told author Philip Norman in an interview for Rave On: The Biography of Buddy Holly, "… . to see someone so honest and so completely himself was super-refreshing. He wasn't the world's most handsome guy, he didn't have the world's most beautiful voice, but he was himself."

The songs recorded at Petty's studio were turned down by Roulette, Columbia, RCA, and Atlantic Records before Holly placed them with Coral/Brunswick. Ironically, the label was a subsidiary of Decca, the same company that had dropped Holly the previous year. Because Decca owned the rights to the earlier recording of "That'll Be the Day," Brunswick credited the song to the Crickets upon its release in May 1957. The song was a slow-building hit, finally hitting the top of the U.S. singles charts on September 23. Holly and the Crickets spent the intervening months touring the country in package shows with other acts. They became one of the first white acts to perform at Harlem's famous Apollo Theater. Appearances on such television programs as American Bandstand and The Ed Sullivan Show further increased their visibility. The band's first album, The Chirping Crickets, was released by Brunswick in November 1957. "That'll Be the Day" became a major hit in Britain as well, encouraging the Crickets to tour there in March 1958.

Further singles followed, some credited to Holly, others to the Crickets. "Peggy Sue," perhaps Holly's most recognizable song, reached number three on the U.S. singles chart in January of 1958. The song's rumbling beat and stark, clear-toned guitar playing were unique for the time, as were Holly's idiosyncratic, hiccup-accented vocals. "Oh Boy," "Maybe Baby," and "Rave On" continued his success into the spring and summer of that year. These and other Holly records represented major innovations in the still-fledgling rock 'n' roll genre. His use of multi-track recording techniques and reliance on largely self-written material were widely imitated. Rather than conforming to the rock 'n' roll sex symbol image popularized by Presley, the gangling, bespectacled Holly set a different standard for pop music stardom. The instrumental line-up of the Crickets— two guitars, bass, and drums—became the prototype of countless rock bands who followed a few years later.

Compared to such flamboyant rock 'n' roll peers as Little Richard and Jerry Lee Lewis, Holly led a conservative lifestyle. Playful and exuberant on stage, he was shy and introverted when not performing and was prone to taking long solitary drives in the Texas desert. His exterior meekness disguised an inner self-confidence and drive which grew as his success increased. The summer and fall of 1958 brought considerable changes in his life. On August 15, he married Maria Elena Santiago, a publishing company receptionist Holly had met in New York two months earlier. That October he parted company with producer/manager Petty and split with the Crickets as well. His career was heading in new directions: that fall he produced the first recording by a then-unknown Waylon Jennings and began experimenting with string section backup on his own recordings. In November 1958 he recorded four songs with the Dick Jacobs Orchestra—including the Paul Anka-composed "It Doesn't Matter Anymore" and Holly's own "True Love Ways"—that found him moving away from frenetic rock 'n' roll and toward more polished pop balladry.

In January 1959, Holly made what would prove to be his last recordings at his apartment in New York City's Greenwich Village. That same month, he embarked on a "Winter Dance Party" tour with a newly formed backup group which included guitarist and former Cricket Tommy Allsup, drummer Carl Bunch, and bassist Waylon Jennings. The tour, which also included such acts as J.P "Big Bopper" Richardson, Richie Valens, and Dion and the Belmonts, stopped in Clear Lake, Iowa, on February 2. Tired of traveling in his poorly heated tour bus, Holly chartered a small Beechcraft Bonanza plane to travel to the next concert stop in Moorhead, Minnesota. The plane, carrying Richardson and Valens along with Holly, took off at one a.m. in severe winter weather. It crashed a few minutes later not far from the airfield, killing all on board.

News of Holly's death at age 22 sparked a genuine sense of loss in America, Great Britain, and elsewhere. The tragedy helped to make "It Doesn't Matter Anymore" a posthumous hit, the first of many to follow. In May of 1959 Coral Records released The Buddy Holly Story, a retrospective album that stayed on the charts for three years and became the label's biggest-selling release. Old Holly tunes revived or discovered included "Midnight Shift," "Peggy Sue Got Married," "True Love Ways," and "Learning the Game." Former producer Petty acquired the rights to a number of Holly's recordings and released them with over dubbed additional musicians. Holly's recordings remained in print and sold well, particularly in Great Britain where the "best of" collection 20 Golden Greats topped the charts in 1978.

The following decades demonstrated Holly's continued influence on popular music. Both the Beatles and the Rolling Stones performed and recorded his songs at the start of their careers. Such rock artists as Bob Dylan, Elton John, and Bruce Springsteen acknowledged their creative debt to Holly in interviews. Singer/songwriter Don McLean's 1971 hit "American Pie" mourned his death as "the day the music died." Linda Ronstadt, the Knack, and Blondie were among the pop/rock artists who revived his tunes in the 1970s. In 1975 Paul McCartney purchased Holly's entire song catalogue and, a year later, commemorated the late singer's 40th birthday by launching "Buddy Holly Week" in Great Britain. Recognition continued into the 1980s, when Holly became one of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame's original inductees. Such tribute albums as 1989's Everyday Is a Holly Day and 1996's Notfadeaway: Remembering Buddy Holly featured new interpretations of his material. Holly's life was brought to the screen in the 1978 film The Buddy Holly Story, which earned lead actor Gary Busey an Academy Award nomination.

Over 40 years after Holly's death, his recordings continued to rank among the most significant in modern popular music. What course his work might have taken had he lived remains one of the great unanswered questions in rock 'n' roll history. Beyond such speculation, Holly's music continues to be played and enjoyed, and his presence missed.

All Music Guide, edited by Michael Elewine, Vladimir Bogdanov, Chris Woodstra, and Stephen Thomas Erlewine, Miller Freeman Books, 1997.