Bruce Haack biography

Date of birth : 1931-05-04

Date of death : 1988-09-26

Birthplace : Alberta, Canada

Nationality : Canadian

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-11-19

Credited as : musician, composer, pioneer of electronic music

0 votes so far

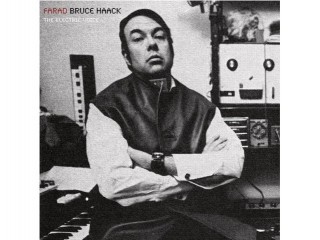

In addition to writing music for dance productions, he also authored songs for pop singers, wrote jingles for products as diverse as life insurance and Kraft cheese, and appeared on television variety shows to demonstrate the Dermatron synthesizer. While he built a small but loyal following with his children's albums, Haack's one major-label release--The Electric Lucifer, distributed by CBS Records in 1970--was less successful. Although it was later hailed as "perhaps the most awesomely bizarre psychedelic pre-Kraftwerk electronica album ever to be released on a major label" by an Aquarius Records reviewer, it was apparently too avant-garde for its time. Haack continued to produce commissioned pieces, children's albums, and electronic music in the 1970s and 1980s until failing health diminished his output. In the decade after his death in 1988, Haack's work was reissued and a new generation of fans have rediscovered his pioneering contributions.

Haack was born on May 4, 1931, in the western Canadian town of Nordegg, Alberta. He grew up in the town of Rocky Mountain House, Alberta, where the Canadian prairie meets the Rocky Mountains. As the only child of Clark Russell and Bertha Ann (Bell) Haack, young Haack's life was a solitary one. His father was an accountant who suffered the aftereffects of polio and his mother, a hypochondriac, was in and out of hospitals throughout her life. Aside from the weekly highlight of a train coming through town to deliver coal, Haack had to invent his own amusements to keep himself company. From the age of three he played on the family's piano; by the time he was a teenager, he was giving piano lessons to neighbors. He even played in some country-and-western bands around Rocky Mountain House as a teenager.

Despite his obvious talent for music, Haack failed to gain acceptance to the music program at the University of Alberta in the province's capital, Edmonton. Largely self-taught, his skills at notation, or writing music, were the cause of his rejection. Undaunted, he studied psychology at the university while participating in music-related activities on campus. By the time he graduated in 1954 Haack hosted a radio show, played in a band, and wrote music for some student stage productions.

Having demonstrated his musical abilities, Haack submitted an audition tape to the Juilliard School in New York City, one of the finest music programs in the world. With scholarships from Juilliard and the Canadian government, Haack went to New York in 1954. Intending to major in composition, he worked with Vincent Persischetti. His stay at Juilliard was brief, however; he left after just eight months, frustrated by the school's highly structured program of study. Despite dropping out of the program, Haack remained in New York through the early 1970s.

From the start of Haack's professional career, diversity marked the young composer's work. Mainstream audiences were probably most familiar with his songwriting work, which included a couple of songs for Theresa Brewer, one of the 1950s most popular female singers. He also wrote musical scores for corporate-sponsored events, theater productions, and dance performances. Haack also began collaborating with Ted Pandel, who sometimes worked under the name Praxiteles. The two became lifelong partners, and when Pandel secured a teaching job in West Chester, Pennsylvania in the early 1970s, Haack was finally free to pursue music as a full-time vocation. In the meantime, however, he made a living through a number of odd jobs, often making a few dollars as a dance recital accompanist.

While working as a pianist for a dance class, Haack met Esther Nelson, who had a deep interest in elementary education. Haack and Nelson struck up an immediate friendship; as she recalled in an interview with the Emperor Norton record label website, "He was a true genius--and he was fabulous with the kids. They just adored him! He would actually climb right inside the piano! He'd put all these things into the piano to change the sound. I guess that's called 'preparing' the piano; he also had a million instruments that he would bring to class." While Haack's methods may have been unconventional, the children in the class did indeed love his antics. Soon, parents began asking if Nelson and Haack could make tapes for them to use with their children at home. The duo obliged by forming their own record label in 1963 on a shoestring budget and recording an album in the living room of Haack and Pandel's 71st Street apartment.

Nelson and Haack decided to call their record label Dimension 5 in reference to the power of imagination, or the fifth dimension, in life. While Haack and Pandel handled most of the recording duties, Nelson ran the business side of the label. She was able to get their first album, Dance, Sing, and Listen, included in some educational catalogues and with a series of positive reviews, Nelson and Haack went on to make two additional Dance, Sing, and Listen albums through the mid-1960s. As Nelson later described the content of the albums to an Emperor Norton interviewer, "Strange and wonderful creations all; the avant-garde elements tempered with a witty, personable, and totally unaffected delivery. They displayed a rare and genuine understanding of their target audience--children. Where most kiddie fare will lapse into hideous 'pooky-wooky' baby-talk, the Dimension 5 albums speak to kids as if they were, like, human beings or something." As George Zahora of the Pop Matters website put it, "He's really not like anyone else you've heard before. Though it wouldn't seem that unusual to today's experimental rock fans, this stuff must have been utterly mind-blowing in the sixties." Nelson and Haack continued to work together for the rest of their lives, including a series of Songbook albums on the Dimension 5 label in the mid-1980s.

Given the difficulties of making a living as a part-time piano accompanist and children's educator, Haack also took on more lucrative work in the advertising field. He wrote the scores for numerous radio and television advertisements in the 1960s. Among Haack's most important accounts were the jingles for Lincoln Life Insurance, Kraft cheese, Goodyear tires, and Parker Brothers board games. Haack also appeared on television shows that ranged from The Mister Rogers Show on PBS--where he and Nelson showed how to play a synthesizer--to The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson. One of the standard talk-show bits that Haack and Pandel used involved the Dermatron, a synthesizer that responded to heat and touch. In one memorable performance, the two appeared on the game show I've Got a Secret with Victor Borge, who used the Dermatron to "play" a line of 12 women hooked up to the device.

After the release of two more children's records on Dimension 5, The Way Out Record for Childrenin 1968 and The Electronic Record for Children in 1969, Haack obtained a contract with CBS Records. As it turned out, he recorded only one album for the label, 1970's The Electric Lucifer. Even by the standards of the psychedelic era, the album's theme--a war between heaven and hell, with the force of "powerlove" winning out--was anything but ordinary. Haack later returned to the theme in his later work, but the sessions were never released.

After moving from New York City to West Chester, Pennsylvania, Haack continued to make electronic music for adults and children. Among his major works were the more pop-oriented electronic album Together, released under the pseudonym Jackpine Savage in 1971, and the children's albums Dance to the Music, Captain Entropy, This Old Man, and Ebenezer Electric, an electronic rendering of A Christmas Carol. In one of the more unusual of Haack's collaborations, he also worked with singer and ukulele player Tiny Tim on the 1981 release Zoot-Zoot-Zoot, Here Comes Santa in His New Space Suit. On the more conventional side, Haack also undertook a number of commissioned music projects for the Scholastic Book Company's magazine and record division.

While Haack remained an active collaborator with Nelson in the 1980s, diabetes-related health problems slowed down his prolific output. He died in his sleep on September 26, 1988, of heart failure. After his death, Dimension 5 continued to release compilations of his work and arranged for additional releases on the Emperor Norton label. In a tribute to Haack's lasting impact on the contemporary musical landscape, a tribute album was announced in 2001 with planned contributions from Beck and Stereolab, among others.

Selected discography:

-(With Esther Nelson) Dance, Sing, and Listen , Dimension 5, 1963.

-(With Esther Nelson) Dance, Sing, and Listen Again! , Dimension 5, 1963.

-(With Esther Nelson) Dance, Sing, and Listen Again & Again! , Dimension 5, 1965.

-The Way Out Record for Children , Dimension 5, 1968.

-The Electronic Record for Children , Dimension 5, 1969.

-The Electric Lucifer , CBS, 1970.

-(As Jackpine Savage) Together , Dimension 5, 1971.

-Dance to the Music , Dimension 5, 1972.

-Captain Entropy , Dimension 5, 1973.

-This Old Man , Dimension 5, 1974.

-Ebenezer Electric , Dimension 5, 1976.

-Funky Doodle , Dimension 5, 1976.

-Bite , Dimension 5, 1981.

-(With Tiny Tim) Zoot-Zoot-Zoot, Here Comes Santa in His New Space Suit , Ra-Jo International, 1981.

-(Contributor) The Silly Songbook , Dimension 5, 1986.

-(Contributor) The Fun-to-Sing Songbook , Dimension 5, 1987.

-(Contributor) The Funny Songbook , Dimension 5, 1987.

-The Electronic Cassette for Children , Dimension 5, 1987.

-(Contributor; as Jacques Trapp) Everybody Sing and Dance , Dimension 5, 1988.

-(Contributor) The World's Best Funny Songs , Dimension 5, 1989.

-Hush Little Robot , QDK, 1998.

-Listen, Compute, Rock Home: The Best of Dimension 5 , Emperor Norton, 1999.