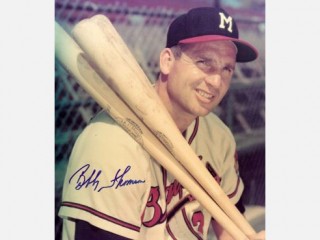

Bobby Thomson biography

Date of birth : 1923-10-25

Date of death : 2010-08-16

Birthplace : Glasgow, Scotland

Nationality : Scottish

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-08-24

Credited as : Baseball player MBL, played for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Giants

0 votes so far

Bobby inherited his athletic skills from his father, who had been a fitness instructor in the British military. The Thomsons liked baseball. They rooted for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Bobby attended Curtis High School in Staten Island from 1938 to 1942. He excelled in soccer and baseball for the Warriors, growing to a lanky 6–2 by the time he graduated at age 18. Being in the backyard of the Giants, Bobby was scouted and eventually signed by George Mack the day after he received his diploma. His starting salary was $100 a month.

Bobby began his professional career with the Bristol Twins in the Appalachian League. After a week, he was transferred to Rocky Mount of the Bi-State League. Both were D-level circuits. Bobby got into 22 games for the Rocks at third base and hit .241.

NFor the next three years, Bobby barely played all of an inning of baseball. He entered the Air Force in December of 1942 and became a bombardier. While many big league ballplayers were given duties as fitness instructors and used as ringers on base teams, Bobby was an unknown in 1943 when he earned his wings at George Air Force Base, near Los Angeles. As luck would have it, Thomson’s crew never saw hostile action during the war.

After the Japanese surrendered in 1945, Bobby began playing semi-pro ball in Southern California while waiting for his official discharge. He was surprised how quickly his rhythm returned after such a long layoff. The Giants’ West Coast scouts reported that Bobby had filled out and was now crushing the ball.

The following spring the team brought him in for spring training in Jacksonville and played him with their minor leaguers. He showed enough to earn a promotion to the Class-AAA Jersey City Giants for the 1946 season. Bobby’s first game there also marked the debut of Jackie Robinson in pro baseball.

Bobby played third base for the “Little Giants,” as they were sometimes called by the scribes. He smashed a team-record 26 homers, double that of teammates Mickey Grasso and Les Layton, who tied for second with 13. Bobby also led the club with 149 hits, 93 runs, 92 RBIs and 15 stolen bases. In early September, he received the call to the Polo Grounds. Bobby got into 18 games for New York. He batted .315 and launched two home runs for the last-place Giants.

ew York had tried several options at third base in ’46, including Sid Gordon, Bill Rigney, Buddy Kerr and Mickey Witek. Not one of them was the answer for manager Mel Ott. There were also questions about Bobby, who didn’t exactly thrill anyone with his defense. The following spring in Phoenix, he looked to crack the team’s outfield corps. Gordon and Willard Marshal were set at two of the spots. Bobby’s live bat and tremendous speed helped him nail down the center field job.

The Giants experienced a welcome turnaround in 1947. Bobby, who played in 138 games, was a big part of the team’s rise in the standings. New York improved by 20 victories to go 81–73, good for fourth place in the National League. The Giants won thanks to a band of booming bats. Bobby slammed 29 homers to go with 51 by John Mize, 35 by Walker Cooper and 36 by Marshall. New York easily led the NL with 221 round-trippers. Only the St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates managed to hit more than 100 long balls. And only one other player not in a New York uniform—Ralph Kiner—hit more homers than Bobby, who added 85 RBIs and 105 runs scored.

The Giants dropped to fifth in 1948, but they still had a winning record. Bobby moved over to right field, where he would ultimately play most of his career. A sophomore slump dragged his batting average down to .248 and cut hit homer output by nearly half, to 16. Even so, he was recognized as one of the league’s budding talents. Rewarded with a trip to his first All-Star Game, Bobby pinch-hit for Ewell Blackwell leading off the ninth and went down on strikes, as Joe Coleman of the Philadelphia A’s finished off a 5–2 victory for the American League.

The following season proved to be Bobby’s breakout year. In 1949, he led the Giants with 27 homers, 99 runs, 198 hits, 109 RBIs, 35 doubles and nine triples. His .309 batting average, also tops on the team, was sixth-best in the NL. He returned to the All-Star Game, serving as a pinch-hitter once again. This time he batted in the sixth inning and represented the go-ahead run in an 8–7 game. Bobby flew out against Lou Brissie to end the threat. The AL tacked on three runs moments later to win 11—7.

The 1950 season was New York’s third under skipper Leo Durocher. “The Lip” was starting to build a club that reflected his personality. The Giants finished third behind the Philadelphia Phillies and Dodgers in an exciting pennant race.

Bobby may not have had Durocher’s feistiness, but he was a smart, tough competitor who provided much of the pop in the Giants’ lineup. Even so, he was never one of his manager’s favorites. Durocher would tell writers privately that Bobby was too easygoing, and that he could play like Joe DiMaggio if he drove himself harder. These viewpoints, often unattributed, invariably showed up in the papers when reporters wrote about Bobby.

But, really, what was not to like? Bobby ended up leading the team with 25 home runs in ’50 and was second with 85 RBIs. His .252 average was a disappointment, but the team as a whole batted just .258—the third-lowest mark among all major league clubs.

The 1951 campaign began with Bobby in center field, but by the end of May, Durocher had made him a utility player. His reasoning was solid—he watned to get rookie Willie Mays into the lineup. Bobby split time with Hank Thompson at third base and also spelled Monte Irvin and Don Mueller at the corner outfield positions. In all, he played in 148 games and led the Giants with 32 homers, 67 extra-base hits, and a .562 slugging average. The combination of Bobby’s bat and his willingness to make way for the sparkplug Mays was one of the major reasons why the Giants were able to catch the front-running Dodgers in September and force a three-game playoff for the NL pennant.

Bobby’s home run total stood at 30 after 154 games. He hit number 31 in the first playoff game against Ralph Branca, as New York took the opener 3–1 at Ebbets Field. With the remaining contests scheduled for the Polo Grounds, the Giants were seemingly in good shape. But Brooklyn administered a 10–0 shellacking in the second contest to set up the decisive third game.

Sal Maglie got the starting nod for the Giants, and Don Newcombe took the hill for the Dodgers. Down 1–0 in the bottom of the seventh, New York knotted the score when Bobby brought home Irvin from third base on a sacrifice fly. Maglie tired in the eighth, allowing three runs, while Newcombe held the Giants in the bottom half of the inning. Newk was spent as the ninth began and lobbied to be removed, but Robinson talked him into staying in the game.

With the Giants trailing 4–1, Alvin Dark started New York’s rally with a single. Don Mueller followed with a well-placed roller through the infield to right. With runners on first and third, Irvin popped out. Whitey Lockman next drove a double to left with an inside-out swing. Dark scored, while Mueller slid awkwardly into third base and broke his ankle. Play stopped for several minutes as he was removed from the field and Clint Hartung took his place.

During the break, Brooklyn manager Chuck Dressen decided to give Newcombe the hook. Right-handed Carl Erskine and the left-handed Branca were both loosening in the pen. Coach Clyde Sukeforth noticed that Erskine bounced one of his curves and advised Dressen to go against both common lefty-righty wisdom—and recent history—and call for the southpaw. Sukeforth would shortly be out of a job.

Bobby stepped to the plate with one out, runners on second and third and the Giants down 4–2. Branca burned his first pitch over for strike. Ahead in the count, he decided the best way to get Bobby out was to make him swing at a slider low and away. To set it up, he threw a fastball up and in. Normally, Bobby was a low ball hitter, so Branca expected him to lean back and take the high, hard one. But having let the previous pitch go down the middle, Bobby was determined to hack at anything that looked close.

Bobby crushed the pitch and sent a looping liner toward left field. Andy Pafko moved as if he expected a rebound off the wall, but the drive cleared the fence at the 315-feet sign for the pennant-winning home run that would become known as The Shot Heard ’Round the World. As Bobby galloped gleefully around the bases to the waiting arms of his teammates, Robinson watched to make sure he touched every bag.

A half-century later, a story surfaced that the Giants had engaged in an elaborate sign-stealing scam, with coach Herman Franks hidden in Durocher's office, where he could see the catcher. Franks supposedly buzzed the pitch to the bullpen, where a fastball-curveball signal could be flashed to the batter. In this case, Franks would have been swiping signals from backup catcher Rube Walker. Thomson denied that he had foreknowledge of Branca’s pitches.

What Bobby did admit to was not fully understanding the magnitude of his home run. As he rounded the bases, he was elated to have beaten the Dodgers. It would be several hours before he grasped the historic significance of his swat. He later learned that his mother, who was too nervous to attend the game, spent the day cleaning the house. His father had long since passed away; one of Bobby’s great regrets was that his father never got to see him as a major leaguer.

From the heights of their victory over the Dodgers, the Giants had to pull themselves together and focus on playing their cross-river rivals, the Yankees, in the World Series. This would be Bobby’s only trip to the Fall Classic, and it was not one he cared to remember. New York hurlers shackled him in the series, limiting Bobby to a pair of singles and no RBIs. The Giants won two of the first three games behind the pitching of Dave Koslo and Jim Hearn, but the Yanks ran the table after that. They won the championship in six games.

The Giants and Dodgers seemed destined to repeat their thrilling pennant battle in 1952. Early in the season, however, it looked like a wire-to-wire job by New York, which started the year winning 16 of 18. But Brooklyn gnawed away, cleaning up against the second-division clubs and getting a big year out of unheralded rookie Joe Black. The Giants, meanwhile, were without the services of Mays (due to military service) and Irvin (because of a broken ankle) most of the season. That was enough to drop them into second place behind the Dodgers.

Durocher again used Bobby as a swingman rather than an everyday player. He roamed center in Mays’s absence and third when Thompson wasn’t stationed there. Bobby topped the club with 24 homers and tied Dark for the team lead with 29 doubles. He also led New York with 108 RBIs, but that didn’t stop fans from booing him when he left men on base. They expected him to win the pennant with every swing.

One thing that got the fans cheering was Bobby’s talent for legging out triples. He had 14 in 1952, which put him two ahead of Enos Slaughter for the NL crown—it was the one and only time Bobby led the league in a major offensive category. He made his third and final All-Star appearance that July, makingearning a spot in the starting lineup at the hot corner. He batted twice in the rain-shortened NL victory, flying out to Hank Bauer in deep right-center and popping out moments after Hank Sauer belted what would prove to be the game-winning home run. It was yet another highlight in a magical season for Sauer, who would go on to be named NL MVP.

The highlight for Bobby in ’52 came two days after Christmas when his biggest fan, Elaine Mae Coley, said, “I do.” Bobby and “Winkie” we married for more than 40 years and had a son and two daughters. Bobby was still living at home in Staten Island with his mom when he and Elaine tied the knot. The young couple soon moved to suburban New Jersey.

The newlywed returned to the outfield in 1953, playing center field in Mays’s continued absence. He reproduced his ’52 numbers, leading the club with 26 homers and 106 RBIs. The rest of the lineup hit well, but it was not enough to make up for an erratic pitching staff. The result was a disappointing 70–84 record. Disappointing because Durocher felt that he had the makings of a good mound crew, anchored by young starter Ruben Gomez, the ageless Maglie and ace reliever Hoyt Wilhelm. But veterans Jim Hearn and Larry Jansen were wearing down, and the bullpen had yet to sort itself out.

That changed in 1954, when Durocher got clutch performances from virtually every member of his staff. The key addition was Johnny Antonelli, a former Bonus Baby with the Braves. He went 21–7 for New York and—with an MVP season from Mays—the Giants cruised to the pennant.

The cost to bring Antonelli over from Milwaukee was dear. The Giants had to part with Bobby in a six-player deal that also netted them Don Liddle, who would prove to be a valuable contributor as well. Fans suspected the trade was linked to the two-year contract given to Durocher midway through 1953. Leo felt that Bobby would be expendable when Mays came back from the service and, indeed, he was the first to go that off-season. Giants owner Horace Stoneham, who adored Bobby, seemed genuinely sad that he had to send his mild-mannered power hitter away.

Bobby was unhappy about leaving New York but excited to be going to baseball’s most supportive town. In 1953, the Braves moved to Milwaukee after eight decades in Boston. The fans came in droves to see their new team, led by young slugger Eddie Mathews and twin aces Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette. Manager Charlie Grimm penciled Bobby into left field, beside speed demon Billy Bruton. With Bobby and Joe Adcock providing right-handed protection for the lefty Mathews, Milwaukee’s lineup figured to be one of the most formidable in baseball.

This plan changed in an instant during a spring training game in 1954 against the Yankees. Bobby attempted to stretch a single and snapped his ankle sliding into second base. Even under ideal conditions, Grimm knew he would be without his new left fielder until the second half, so he turned to two players: Jim Pendleton, the team’s fourth outfielder, and Hank Aaron, a 20-year-old converted infielder. Pendleton had been a holdout, and when he finally showed up, he was carrying an extra 20 pounds. While he worked his way into shape in March and April, Aaron took the left field job away. The crowning blow came against the Red Sox. Aaron sent a rifle shot over the fence. When Boston’s Ted Williams heard the sound he asked, “Who the hell was that?” When informed it was the busher Aaron, he told reporters to remember that name. They'd be writing about him for a long time.

Aaron did a fine job in Bobby’s absence, but the Braves just didn’t have the horses to make any noise in the NL. Bobby returned to the team in July, but Milwaukee was already beginning to fade. The team finished third, eight games out, behind the Giants and Dodgers. In 43 games, Bobby managed just two home runs and a .232 average. He did not run well. In fact, “The Flying Scot” would never run well again.

Which is not to say Bobby was washed up. On the contrary, the year after his ankle injury, Bobby moved back into left field with Aaron shifting to right. The Braves looked like champs, and many experts picked them to reach the World Series. Unfortunately, the Dodgers ended this dream by winning 22 of their first 24 games, and then maintaining a double-digit lead in the standings most of the summer.

The Braves felt the sting of the injury bug again. This time Adcock went down, which sapped the strength from the Milwaukee lineup. Bobby had a decent year, but he was still hobbling. Unable to fill the void left by Adcock, he played 101 games and contributed 12 homers and 56 RBIs.

Bobby returned to full-time duty in 1956, and this time the Braves made a race out of it. After a sluggish start that cost Grimm his job, they battled the Dodgers and Cincinnati Reds all season long. On September 1, Milwaukee looked to have the strongest team for the stretch run. But slumps by key players—including Mathews, Adcock and Burdette—left the Giants a game behind Brooklyn when the season ended. Bobby increased his home run output to 20 and added 74 RBIs. His .235 average raised some eyebrows in Milwaukee’s front office, and after the season, the Braves let it be known that Bobby was available.

After surviving the off-season and spring training, Bobby was still a Brave when the 1957 season opened. In an ironic twist of fate, the Giants had the puzzle piece the Braves needed—second baseman Red Schoendienst—and Bobby was the player offered in return. So on June 15th, he went back to New York, along with Danny O’Connell and Ray Krone. The Milwaukee brass knew what it was doing. The Braves’ new acquisition led them to the pennant, just as Antonelli had done three years before. Bobby played 41 games for the first-place Braves and 81 for the sixth-place Giants. He hit 12 homers and drove in 61 runs.

Bobby accompanied the Giants to San Francisco in 1958, but only on paper. At the end of spring training, the team sent him to the Chicago Cubs for Bob Speake and cash. With young guns Mays, Felipe Alou, Leon Wagner and Willie Kirkland in camp, the Giants didn’t have much room for a 34-year-old sore-ankled outfielder.

The Cubs were a much better fit for Bobby. They employed a power-hitting, station-to-station offense featuring Ernie Banks, Lee Walls, Walt Moryn, Dale Long and Cal Neeman. Manager Bob Scheffing inserted Bobby in center field, and he proceeded to hit .283 with 21 homers and 82 RBIs. He led the Cubs with 27 doubles and trailed only Banks and Walls for the team lead with 155 hits. The Cubs finished in a fifth-place tie despite an MVP season from “Mr. Cub.”

George Altman became Chicago’s everyday center fielder in 1959, moving Bobby over to right field. Unlike the previous season, the Cubs had enough pitching to make the club competitive, but this year the offense fell flat. With the exception of Banks, no one had a good year. Bobby managed a mere 11 home runs in 122 games. After the season, he was dealt to the Red Sox for journeyman right-hander Al Schroll.

In Boston, Bobby was part of an outfield that included Williams, who was playing his last season. Bobby wasn’t around to see the Splendid Splinter’s epic final game. Despite hitting five homers in the season’s first 10 weeks, he was released on July 1st. Baltimore snapped him up three days later, and Bobby found himself in the midst of a pennant race, as the young Orioles were giving the Yankees and Chicago White Sox all they could handle. Bobby wasn’t around for the finish of that story, either. Baltimore released him at the end of the month after he went hitless in six at-bats. Bobby finished his career with 1,026 hits, 264 home runs, and a .270 average.

Bobby decided it was time to go home to Elaine and his three kids— Megan, Nancy and Robert Jr.—in Watchung, New Jersey. Bobby’s transition to the business world was not a smooth one, however. He really didn't know how to talk to people outside of a baseball clubhouse, and he didn’t trust his decision-making off the diamond. He paid $150 to be tested at Stevens Tech in Hoboken to help determine what type of post-baseball career would suit him best. At the top of the list was industrial sales. That was good news. He had a name that could get him in to see any baseball-loving executive in America.

After considering offers from several companies, he chose West Virginia Pulp and Paper (aka Westvaco), a company that produced paper bags for some of the biggest corporations in the world. He worked for them for more than three decades. For much of that time, Bobby’s office was in New York—not far from Ralph Branca’s insurance office. The two made good money showing up together for sports banquets and other events, and they eventually became close. As Branca liked to say, “I lost a game but I made a friend.”

From his universal fame as a ballplayer, Bobby went to “riding the subway with the rest of the working stiffs” and claimed he adored every minute of it. He retired to Watchung and then in 2006 moved to Savannah, Georgia, 13 years after Elaine and Robert Jr. had both passed away. Bobby died on August 16, 2010. He had been in declining health and had recently had a bad fall.

When he looked back on his career, Bobby always did so with a little disappointment. He admitted that, after 1951, fans expected him to homer every time he stepped to the plate—almost like he was some kind of circus freak—and that as hard as he tried to ignore this, he was sure that it affected his performance. He lamented the fact that he never lived up to his potential, that he failed to be a consistent .300 hitter.