Blind Lemon Jefferson biography

Date of birth : 1893-09-24

Date of death : 1929-12-19

Birthplace : Coutchman, Texas, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-12-05

Credited as : blues singer, guitarist, "Father of the Texas Blues"

1 votes so far

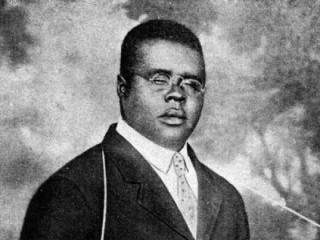

Blind Lemon Jefferson emerged in the 1920s as one of the most popular and imitated blues guitarists of the decade. As an early exponent of the Texas blues style, Jefferson's recorded performances exhibited an array of unique and inventive musical ideas. His sides for the Paramount label found their way into the repertoires of numerous bluesmen, influencing both country and urban blues stylists throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Despite Jefferson's musical contribution, information regarding his life-- limited to one surviving photograph and scant recollections by local eyewitnesses and fellow musicians--has left little to reveal the man behind the music. Sixty years after his death, Jefferson's catalogue of nearly one hundred recordings reveal the musical power and poetic storytelling ability of an American folk music legend.

Lemon Jefferson--the 1900 Freestone census lists one member of the Jefferson family as Lemmon B. Jefferson--was born the youngest child of Alec Jefferson and Classie Banks near Couchman, Texas on July 11, 1897. Believed to be blind at birth, Jefferson was able to offer little help to his farming family. Without an education he took up music and worked as an itinerant musician, performing on streets and local functions outside Wortham, Texas. He also appeared as a singer at local church events such as the General Association of Baptist Churches in Buffalo, Texas.

Jefferson later traveled through towns along the H & TC Railroad-- Groesbeck, Martin, and Kosse--and around 1912 performed in the Deep Ellum section of Dallas. With a tin cup wired to the neck of his guitar, he played for tips on the streets, often performing slide guitar numbers, a technique which utilized a small metal or glass cylinder on a finger of the chord hand to produce voice-like chords and melodies. While in Dallas in 1912, Jefferson joined up with an older musician, Huddie "Leadbelly" Ledbetter. Years later, Leadbelly recalled, in The Life and Legend of Leadbelly, his experiences performing with Jefferson: "Him and me was buddies. Used to play all up and around Dallas-Fort Worth. In them times, we'd get on the Interurban line that runs from Waco to Dallas, Corsicana, Waxahacie, from Dallas." For an intermittent period of several years the pair traveled extensively, sometimes taking in $150 each weekend. While Jefferson sang and played slide, Leadbelly accompanied his younger companion on accordion, guitar, or mandolin.

In 1917 Jefferson worked at Al Bonner's Place in Gill, Arkansas, and continued to hobo around the deep South, often returning to his home base of Dallas. In Meeting the Blues, Bluesman Mance Lipscomb, who encountered Jefferson in Dallas around 1917, told how the guitarist's popularity on the street led whites to prohibit him from performing downtown: "They gave him the privilege to play in a certain district in Dallas, and they call that 'on the track.' Right beside the place where he stood 'round there under a big old shade tree, call it a standpoint, right off the railroad track. And people started coming in there, from nine thirty until six o'clock that evening, then he would go home because it was getting dark and someone [led] him home." The spot described by Lipscomb was located on the corner of Elm and Central Tracks in Dallas's ethnic enclave known as Deep Ellum.

A few years after Lipscomb's encounter with Jefferson, Aaron "T- Bone" Walker also accompanied the blind guitarist around Deep Ellum. In Meeting the Blues Walker stated, "I used to lead Blind Lemon Jefferson around playing and passing the cup, take him from one beer joint to another. I liked hearing him play. He would sing like nobody's business ... People used to crowd around so you couldn't see him." "Afterwards," as Walker related to Helen Dance in Stormy Monday, "I'd guide him back up the hill, and Mama would fix supper. She'd pour him a little taste."

Around 1922 Jefferson married a woman named Roberta. At that time, "he'd gotten so fat," wrote Samuel Charters in The Country Blues, "that when he played, the guitar sat up on his stomach, the top just under his chin." In the slum areas of Dallas he emerged as the city's most popular street singer. As a songster he entertained crowds by performing a wide musical repertoire such as vaudeville songs, rags, Tin Pan Alley tunes, spirituals, and blues numbers. In the mid 1920s pianist Sam Price brought Jefferson to the attention of his employer, R.T. Ashford, the owner of a Dallas record store and a talent scout for several recording companies (other accounts contend that Price wrote to Paramount's recording director and informed him about Jefferson). Ashford then brought the guitarist to the notice of a Paramount record executive A.C. Bailey. After locating Jefferson on a street in Deep Ellum, Bailey invited the guitarist to attend a recording at the company's Chicago studio.

In the 1920s, when most other major labels sent field units to the South to record blues artists, Jefferson attended out-of-town sessions in the cities of Chicago, Atlanta, and Richmond Indiana. During his first trip to the studio in 1926 he cut his first side, "That Black Snake Moan," in Chicago's Paramount studio. The number became a immediate commercial success and prompted the recording of many more sides. In February 1926 Paramount released the 78 featuring "Got the Blues" and "Long Lonesome," rumored to have sold over one hundred thousand copies. Because of the company's extensive mail order system, there were few African-American folk musicians from Texas to the eastcoast who were not aware of Jefferson's music. As Paul Oliver stated in The New Grove, Jefferson's "Lone Lonesome Blues" brought the "authentic sound of rural blues to thousands of black homes." Jefferson's "Matchbox Blues" was recorded twice by Paramount in 1927, and several decades later found its way into the repertoires of Carl Perkins, Elvis Presley, and the Beatles. Another of Jefferson's popular numbers, "See That My Grave is Kept Clean," was re-recorded by numerous blues artists throughout the South. This number, observed John Cowley in The Blackwell Guide, "has lyrical antecedents to several earlier pieces, among them 'Old Blue,' the nineteenth-century sea shanty 'Stormalong,' the British folk song 'Who Killed Cock Robin' and several spirituals."

In 1927 Jefferson also recorded for the Okeh label in Atlanta, Georgia. Though sales of Jefferson's records waned by the late 1920s, he continued to wear immaculate suits and employed a full-time chauffeur. In 1929 Jefferson recorded his last sides for the Paramount at the Gennett label in Richmond, Indiana. Among the numbers recorded for the Gennett session were "Pneumonia Blues," "The Cheater's Spell," and "Southern Women Blues."

In December 1929, Jefferson died of a heart attack and exposure on a Chicago street, reportedly after his chauffeur abandoned him and his automobile during a snow storm. His body was brought back to Texas and interned in the Negro burying ground of Wortham cemetery. For decades, while Jefferson's unmarked and weed-ridden gravesite existed in small country cemetery, enthusiasts around the world formed societies and publications in his honor. In October 1967 the Texas State Historical Society placed a plaque marking the resting place of one of America's most enduring folk music legends.

Jefferson is considered a musical idol by musicians such as B.B. King, and his recordings continue to awe listeners. In the New Grove, Bitish music writer Paul Oliver described Jefferson's enduring vocal sound: "His voice was high, piercing the traffic noise, but could also have a low, moaning quality extended by 'bending' the notes on his guitar to produce crying sounds or imitative passages on the strings." Jefferson's intricate and erratic guitar work followed broken-time patterns with standard four-four measures and tempo altered to fit spontaneous vocal lines or guitar.

Apart from his stunning and inventive guitar work, Jefferson authored many songs that found their way into the repertoires of musicians from John Lee Hooker to Bob Dylan. "Lemon sang things he wrote himself about life--good times and bad. Mostly bad, I guess," stated T-Bone Walker in Stormy Monday. "Everyone knew what he was singing about." Over a half century after his death, Jefferson's music still haunts listeners with descriptions of a time and culture that existed outside the popular and glamorous images of America's roaring twenties.