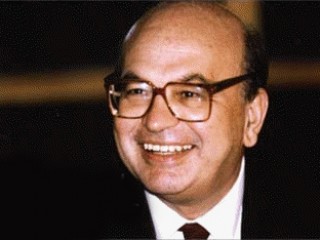

Bettino Craxi biography

Date of birth : 1934-02-24

Date of death : 2000-01-19

Birthplace : Milan, Italy

Nationality : Italian

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2022-02-24

Credited as : Politician and statesman, Prime Minister of Italy,

The Italian statesman Bettino Craxi was the youngest person and the first socialist to become prime minister of the Italian republic. He resigned after three and a half years in office due to problems with his coalition government. In the 1990s he was one of the targets of the largest corruption investigation in Italian post-war history and sentenced to 21 years in prison for his crimes. He went into self-imposed exile in Tunisia

Bettino Craxi (Benedetto "Bettino" Craxi) was born February 24, 1934, in Milan, Italy, where his lawyer father, a Socialist politician, had migrated from his native Sicily. Christened Benedetto, but known by the diminutive "Bettino" ever since he was a child, Craxi as a teenager once thought of becoming a priest. Instead, he turned to politics. At 14 he worked in his father's unsuccessful 1948 campaign for the Chamber of Deputies. At the University of Milan he enrolled to study law, but because of his political commitments he never completed his degree.

At 18 he joined the Socialist Party and was active in its youth movement and its publications. During the next few years he rose steadily through the party's ranks and was elected to local and then national offices. In 1957 he was made a member of the party's national central committee. In 1960, in his first electoral success, he won a seat on the Milan city council. In 1965 he was named secretary of the Socialist Party in Milan and a member of the national party's executive committee. In 1968 he won election to the Chamber of Deputies as a delegate from Milan. He retained that seat in each of the four succeeding general elections.

At the outset of his parliamentary career Craxi was an unknown. According to public opinion polls, 90 percent of the Italian people had never heard of him. Through patient organization and skillful use of contacts, Craxi worked his way to the leadership of the party. In 1970 Craxi became a deputy secretary of the Socialist Party and gradually began to build his power base within the organization. After the Socialists stumbled badly in the 1976 general election, Craxi made a bid for the party's leadership. On July 16 , 1976, he became the compromise candidate for the position of party general secretary.

Craxi's great contribution to the Socialist Party was to revitalize it and to replace a traditional commitment to extremism with one of "pragmatism, gradualism and reform"—according to the platform adopted at the party's 42nd congress in Palermo, Sicily, in April 1981. Craxi tried to present the Socialists as a centrist organization capable of providing direction for a country whose governments had too often been immobilized by factionalism. Some observers have remarked that the Italian Socialist Party has often taken positions that resemble those of Germany's Social Democratic Party, for which Craxi had great admiration.

A vital aspect of Craxi's strategy was to give the Socialists an identity distinct from that of the Communists. Unlike their counterparts in France, Spain, Portugal, and Greece, Italy's Socialists have been constantly overshadowed by the Communists. The latter usually poll three times as many votes in elections and rank a close second in electoral strength to the dominant right-of-center Christian Democrats. In a symbolic gesture, Craxi changed the party's emblem from the hammer and sickle to a red carnation. Although he occasionally cooperated with the Communists to preserve left-of-center political control in some locales, he relentlessly attacked the Communists at the national level. Craxi, and other socialists, accused the Italian Communists of ideological dependence on the Soviet Union. He often expressed doubt publicly that a party with a Marxist-Leninist philosophy could play a legitimate role in a democratic

and pluralist state. In addition to carrying on ideological warfare within his own party, Craxi purged extreme leftists, recruited more moderate replacements, and promoted younger leaders who were personally loyal to him.

Craxi's reforms were made with an eye to changing Italian electoral behavior. The voters, he noted, no longer responded to social class background and were far more sensitive to issue-oriented politics. Craxi also courted new groups emerging in the electorate, especially Italy's rising entrepreneurs, managers, and professionals.

Craxi's efforts to revitalize the Socialists bore fruit for him and for his party. In the party's first major trial of strength under his direction—the May 1978 local elections—the Socialists captured 13.1 percent of the vote, a 3.5 percent improvement over their performance in the general election of 1976. That showing prompted Craxi to nominate the Socialist Sandro Pertini for the presidency of the republic. Pertini was successful and returned the favor when in 1979 he first asked Craxi to form a government. Craxi's first attempt failed, but during the following four administrations between the autumn of 1980 and the spring of 1983, he played a critical role behind the scenes. In the general elections of June 1983 the Socialists made a modest showing with only 11.4 percent of the vote. Nevertheless, the party clearly held the balance of power, and President Pertini once again called on Craxi to form a government. This time he was successful and took office August 4, 1983.

In domestic affairs Craxi led a struggle against inflation and fought for an austerity budget. In foreign affairs he followed a strictly pro-American course. Despite his socialist ideology, Craxi was warmly received by President Reagan in Washington in mid-October 1983. Among the achievements of Craxi's administration were the signing of a concordat with the Vatican in which Roman Catholicism lost its status as the Italian state religion; the use of Italian peacekeeping troops in Lebanon; attacks on the crime "families" of Naples, Sicily, and Calabria; attempts at industrial renewal through new technology; and steps toward welfare and constitutional reform.

One of the major issues of the Craxi government was the growing problem of international terrorism. In 1985 the Italian cruise liner Achille Lauro was hijacked and an American was killed. Palestinian leader Mohammed Abdul Abbas Zaidan and three accomplices were captured in Sicily but released. Then during the Christmas holidays four terrorists attacked the Rome airport. Within five minutes 15 people, including three of the terrorists, were killed and 74 were wounded. By mid-1986 the Italian government had accumulated enough evidence against the ship hijackers to bring 15 to trial in Genoa—ten of them, including Abbas, were tried in absentia. Eleven were convicted. Meanwhile, Craxi's coalition government had stayed in power longer than any Italian government since World War II.

Craxi resigned as Prime Minister after three and a half years in office in March of 1987 citing rifts and irreconcilable differences in his five party coalition. He returned to leading the Italian Socialist Party and representing Milan in Italy's parliament.

In 1992, Mario Chiesa, a socialist politician who headed Milan's largest public charity, was caught pocketing a $6000 bribe. It set off an investigation "Operation Clean Hands" that went on to show that bribe collection was the most efficient and organized arm of the Italian government. Officials routinely skimmed 2 to 14 percent off government contracts for every public service, from airports and hospitals to theaters and orphanages. As the investigation unfolded, all major political parties were implicated: Socialist, Christian Democrat, Democratic Party of the Left (formerly the Communist Party). According to Giuseppe Turani and Cinzia Sasso in their book The Looters, "Operation Clean Hands has hit Italian Politics like a cyclone. After this nothing will be the same."

As head of the Socialist Party, Craxi was urged by party members to purge the party of the wrongdoers. Members of his family were directly involved—Craxi's brother-in-law Paolo Pillitteri was accused of personally accepting suitcases full of money while he was Mayor of Milan and his son Vittorio's election to local office was paid for by Mario Chiesa, whose arrest started the entire investigation. Craxi himself came under investigation, although he fought back, claiming that since all the political parties took the bribes, they must all answer for their crimes. This did not halt the investigation, and ruined Craxi's chances at a comeback as Prime Minister or President of Italy in 1992.

In 1994, Craxi went into self-imposed exile in Tunisia. He was sentenced, in absentia, to 13 years in prison for fraud and in 1996, an additional 8 years after having been found guilty of further corruption charges.

Sources on Craxi in English are scarce. Joseph La Palombara's "Socialist Alternatives: the Italian Variant," in Foreign Affairs (Spring 1982) explains Craxi's role in the evolution of the Italian Socialist Party. Information concerning the scandal that toppled Craxi can be found in articles in the Economist January 23, 1993 and the New Republic August 10, 1992. A complete study of the scandal can also be found in I Sacheggiatori (The Looters) 1992