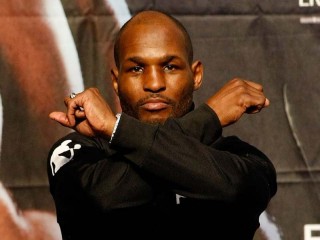

Bernard Hopkins biography

Date of birth : 1965-01-15

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2024-01-15

Credited as : Boxer, known as The Executioner, has a world middleweight title

1 votes so far

Bernard Hopkins: Life and achievements as a Professional Boxer

Bernard Hopkins Jr, known as The Executioner (born January 15, 1965, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) is an American former professional boxer who competed from 1988 to 2016. He is one of the most successful boxers of the past three decades, having held multiple world championships in two weight classes, including the undisputed middleweight title from 2001 to 2005, and the lineal light heavyweight title from 2011 to 2012.

Bernard Hopkins has been nicknamed "The Executioner" (and later "The Alien") for the way he dispatches opponents and for the way he enters the ring before a fight--with his minions following him clad in enormous black hoods and carrying huge axes. Despite his showmanship and his penchant for saying the outrageous, Hopkins has become the first undisputed middleweight champion since Marvelous Marvin Hagler. When he outpunched the previously invincible Felix Trinidad in September of 2001, he unified the World Boxing Association (WBA), World Boxing Council (WBC), and International Boxing Federation (IBF) middleweight titles. Hopkins's life outside the ring has come together as well. He has been married to his wife, Jeanette, since 1993, and the couple have one daughter.

Bernard Hopkins was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on January 5, 1965. Life for the undisputed middleweight champion has not always been rosy. The son of Bernard and Shirley Hopkins, he grew up in Philadelphia as one of eight children. From an early age Hopkins was an aggressive child and seemed to attract trouble. In 1979 at the age of 13 he was stabbed on the subway and suffered a punctured lung. The knife narrowly missed his heart, and he spent six months in the hospital recovering from the attack. As he got older he began to intimidate people. Stealing chains, clothing and money landed him in front of a judge on many occasions. While his high school classmates were graduating, Hopkins was graduating from reform school to the penitentiary. One judge handed the 17-year-old eleventh grader two sentences--one for five to twelve years and one for three to six years. Hopkins told Ron Heard of BoxingTalk.net about his time in prison: "I saw a lot of things in prison that aren't clean or nice to talk about. I was seventeen years old. I didn't consider myself dangerous, but I was surrounded by killers, rapists, child molesters, skinheads, Mafia types, so I was in a dangerous situation. I saw a guy stabbed to death with a makeshift ice pick in an argument over a pack of cigarettes."

Despite the hardships of life behind bars, Hopkins was grateful for his prison experience, because he woke up from his life of petty theft. After almost five years behind bars, the 22-year-old was released, having earned a GED and learned some hard lessons. Hopkins went back to his old Philadelphia neighborhood with nine years of parole hanging over his head, but he also had a resolve to make something of his life despite the odds against him. He decided his avenue to success would be through boxing.

Hopkins started fighting four-round preliminary bouts while working as a cook. His first professional fight, which he lost, came in 1988. The natural middleweight had been stuffed with fast food to move up to the light heavyweight division, where he was sluggish and slow. After the loss and the poor treatment by his manager, Hopkins was so discouraged with boxing that he did not fight again for almost a year and a half. When he returned to the ring, he had a new manager, and fought either as a middleweight at 160 pounds or a super middleweight at 168. Hopkins won 22 straight fights and then in May of 1993 he faced Roy Jones for the IBF middleweight title. The fight should have been his first big payday, but Hopkins maintained he was only paid $70,000 for a championship bout, while his promoter, Butch Lewis, received a $700,000 fight fee. Hopkins lost the fight after he was out-pointed in 12 rounds, and a career that had been on the rise since 1989 seemed to stall.

In 1995 Hopkins captured the vacant IBF middleweight title in a fight with Segundo Mercado, but his career was not taking off. In October of 1996 he was harshly criticized for refusing a second fight with Jones. Hopkins had begun to question the role of boxing promoters and their share of the boxer's purse and, for Hopkins, the issue was not Jones, but the fact that he felt promoter Butch Lewis was taking advantage of him. The Los Angeles Daily News called his situation "pitiable," because he had turned down the Jones fight even though at 30 years old he was still working part-time in a transmission shop to make ends meet. In an article by Jay Searcy of the Philadelphia Inquirer, Hopkins said, "I'll be a grease monkey the rest of my life before I let anybody screw me again. [Lewis] has been underpaying me since I started. I'm not ducking Jones. I've never ducked anybody."

Despite the legal wrangling, Hopkins continued to fight and defend his title, cruising through the middleweight division. But because of his stand against promoters and managers, and perhaps because of the lack of quality in the middleweight division, the million-dollar payday evaded the champion. The only misfortune for Hopkins was a 1998 bout with Robert Allen involving celebrated referee and television judge Mills Lane. While the referee was trying to separate the two fighters, Lane caught Hopkins at an awkward angle and Hopkins fell out of the ring and injured his ankle. The fight was declared a "no contest," but Hopkins would gain a technical knockout over Allen six months later.

Also in 1999 Hopkins was one of the few active fighters to testify before a New York City task force set up to investigate the relationship between boxers and promoters. Hopkins said that several promoters told him not to appear before the panel, but he told Franz Lidz of Sports Illustrated: "Prizefighters get mistreated, exploited, out-and-out robbed every day. Either you crusade for reform or you become part of the problem. As a champion, I feel an obligation to take a stand." Hopkins was both self-managed and self-promoted and perhaps that explains why, after 11 title defenses, he earned $450,000 for his 2000 bout with Syd Vanderpool.

When the undefeated Felix Trinidad moved up to the middleweight division, promoter Don King devised a series of fights among all the middleweight champions that were designed to serve as a way for Trinidad to claim those titles along with the belts he had won when he vanquished Oscar De La Hoya. Hopkins met WBC champ Keith Holmes and Trinidad took on WBA champ William Joppy. Trinidad beat Joppy and Hopkins defeated Holmes in a 12-round decision. The fight between Hopkins and Trinidad was set for September 15, 2001, and the winner would unify the middleweight title for the first time since the mid-1980s. A victory by Hopkins would also tie legendary Argentine Carlos Monzon's record of 15 middleweight title defenses. The whole series of bouts was designed to legitimize Trinidad as a middleweight and then give him a shot at the best fighter in boxing--Roy Jones.

In the usual hype leading up to a major prizefight, Hopkins became known for his Tysonesque ravings. He twice stepped on the Puerto Rican flag to insult Trinidad--who is Puerto Rican--and his fans. The second time, he stepped on the flag while actually in San Juan, Puerto Rico, and provoked a riot. Even when the fight was postponed for two weeks after the September 11th terrorist attacks, Hopkins had the poor taste to wear a baseball cap with WAR printed on it, and to compare Trinidad and his fans to terrorists. At one point his antics almost caused a relocation of the fight from Madison Square Garden in New York City, a venue not far from ground zero, because officials were so offended by his insensitivity. By the eve of the fight, though, both fighters were expressing their solidarity with New Yorkers, and Hopkins had apologized. Hopkins was paid $100,000 by an online casino to wear its website on his back in the form of a temporary tattoo, and he took the entire sum and bet it on himself at 5-2 odds. Few others bet on the 36-year-old fighter against the 28-year-old undefeated Trinidad. The prestige of both fighters was reflected in their purses. Trinidad received $8 million while the long-time champion Hopkins was paid $2.8 million. But a funny thing happened on the way to Trinidad's coronation--Hopkins won.

Because of his inflammatory statements before the fight, the strongly pro-Trinidad crowd booed lustily every time Hopkins's face appeared on the overhead monitors at Madison Square Garden. But Hopkins was such an underdog that by the tenth round, when he had Trinidad on the ropes, the crowd was chanting his name. After the fight even Trinidad called him a great champion and a good fighter. Hopkins told Steve Stringer of The Los Angeles Times that he had a sure-fire strategy coming into the fight: "De La Hoya gave me a little game plan on how to beat Trinidad. He was so confident because he didn't know I was going to be that elusive. Trinidad only has one style of fighting. I knew he couldn't adapt. I kept my right hand glued to my face to take away that left hook. He kept hitting it and hitting it, but he could never get through. About the sixth or seventh round, I knew I had him beat. Once he realized he couldn't hurt me, the fight was over." The fight also marked Hopkins's 14th successful defense of his IBF crown, tying Carlos Monzon's all-time record for middleweight title defenses. He would make that record his own by defeating Carl Daniels on February 2, 2002. Though Daniels made the fight awkward for Hopkins because he is left-handed, Hopkins was too strong and Daniels could not come out for the 11th round. The fight also marked the first time that the 37- year-old fighter was the marquee name and received a big purse on his own merit--$2.5 million.

After achieving unprecedented success on his own terms, Hopkins had only one remaining foe--Roy Jones. The man who defeated him in 1993 and gave him one of his two losses as a professional still held the undisputed title of light heavyweight champion and carried the unofficial title of best pound-for-pound fighter in boxing. Whatever the eventual outcome of Hopkins's career, however, he will remain true to himself. As he told Andre D. Williams of The Morning Call, "A true warrior won't give up, no matter whether they grew up in the suburbs or the ghetto of Philadelphia or the ghetto of Reading. I never gave up. That's why I'm here. Not by a lot of favors but by a lot of hard work and honesty with myself."

A victory over Oscar De La Hoya for the WBO title in 2004 cemented Hopkins' status as undisputed champion, while also making him the first male boxer to simultaneously hold world titles by all four major boxing sanctioning bodies. In 2001, Hopkins was voted Fighter of the Year by The Ring magazine and the Boxing Writers Association of America. In 2011, The Ring ranked Hopkins as third on their list of the "10 best middleweight title holders of the last 50 years." As of April 2021, he is ranked by BoxRec as the seventh greatest boxer of all time, pound for pound.