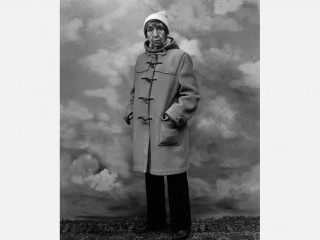

Berenice Abbott biography

Date of birth : 1898-07-17

Date of death : 1991-12-09

Birthplace : Springfield, Ohio

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-17

Credited as : Photographer, ,

Bernice Abbott was one of the most gifted American photographers of the 20th century.

Berenice Abbott's work spanned more than 50 years of the twentieth century. At a time when "career women" were not only unconventional but controversial, she established herself as one of the nation's most gifted photographers. Her work is often divided into four categories: portraits of celebrated residents of 1920s Paris; a 1930s documentary history of New York City; photographic explorations of scientific subjects from the 1950s and 1960s; and a lifelong promotion of the work of French photographer Eug'e Atget. As a woman and a serious artist, Abbott faced numerous obstacles, not least of which was denial of the recognition she was due. Only recently has the high quality of her work been adequately appreciated. As one writer put it, "She was a consummate professional and artist."

Bernice Abbott was born into a world of rigid social rules, especially for women, who were expected to accept without question certain cultural dictates about clothing, manners, proper education, and other areas of everyday life. Abbott was an independent and somewhat defiant girl who hated such arbitrary constraints. One of her earliest acts of "rebellion" was to change the spelling of her name; Bernice became Berenice. "I put in another letter," she told an interviewer, "made it sound better."

Abbott's childhood was not especially happy. Her parents divorced when she was young, and though Abbott remained with her mother, her brothers were sent to live with their father. She never saw them again. This was a severe blow and may partly explain why Abbott never married or had her own family. She said she never wed because "marriage is the finish for women who want to work," and in her era this was largely true.

At age 20 Abbott headed for New York City to "reinvent" herself, as one writer put it. She rented an apartment, studied journalism, drawing, and sculpture, and formed a circle of friends, many of whom were "bohemians" rebelling against the strict social rules of the day. Friends who remembered her from those days said Abbott was shy and "looked sort of forbidding." After three years Abbott had had her fill of New York and decided to go to Paris, something unmarried young women rarely did by themselves. In fact, that such a move was sure to generate controversy probably contributed to Abbott's decision to pursue it.

In Paris Abbott studied sculpture, but she ultimately found it unsatisfying. In 1923 photographer Man Ray, whom she had known in New York, offered her a job as his assistant. Abbott knew nothing about photography but accepted the job. "I was glad to give up sculpture," she said. "Photography was much more interesting." She worked for Man Ray for three years, mastering photographic techniques sufficiently to earn commissions of her own. Indeed, her work became so successful that she decided she had finally found her calling and opened her own studio.

Photographic portraits had become quite fashionable in Paris, and Abbott gained a solid reputation. She photographed some of the most distinguished people of the day, including Irish writer James Joyce; French writer, artist, and filmmaker Jean Cocteau; and Princess Eug'ie Murat, granddaughter of French emperor Napoleon III. Her works have been called "astonishing in their immediacy and insight," revealing much of the personality of her sitters, especially women. Abbott herself commented that Man Ray's photographs of women made them "look like pretty objects"; she instead allowed their character to come through.

While her star was on the rise, Abbott "discovered" some pictures of Paris that she called "the most beautiful photographs ever made." She sought out the photographer, an aged, penniless man named Eug'e Atget. For almost 40 years Atget had been making a poor living photographing buildings, monuments, and scenes of the city and selling the prints to artists and publishers. Abbott's keen eye detected the originality of these photos, and she befriended the old man. When Atget died in 1927, Abbott arranged to purchase all of his prints, glass slides, and negatives—more than a thousand items in all. She became obsessed with this massive collection, spending the next 40 years promoting and preserving Atget's work, arranging exhibitions, books, and sales of prints to raise money. She donated the collection to New York's Museum of Modern Art in 1968, by which time she had almost singlehandedly brought Atget from total obscurity to worldwide renown. Some critics have claimed that Abbott's devotion to Atget's works hampered her career. But she denied this, insisting, "It was my responsibility and I had to do it. I thought he was great and his work should be saved."

Abbott's career took a new turn when she returned to New York in 1929. Inspired by Atget's work and by the excitement she felt in the air, she began a new project: photographing the city as no one ever had. She spent most of the 1930s lugging her camera around, shooting pictures of buildings, construction sites, billboards, fire escapes, and stables. Many of these sites disappeared during the 1930s as a huge construction boom in New York swept away the old buildings and mansions to make way for modern skyscrapers. Several of these photos were published in a 1939 book called Changing New York. In it Abbott wrote, "To make the portrait of a city is a life work and no one portrait suffices, because the city is always changing. Everything in the city is properly part of its story—its physical body of brick, stone, steel, glass, wood, its lifeblood of living, breathing men and women."

This task of documenting the city was not an easy one, especially for a woman. Abbott was "menaced by bums, heckled by suspicious crowds, and chased by policemen." Her most famous anecdote of the period came from her work in the rundown neighborhood known as the Bowery. A man asked her why a nice girl was visiting such a bad area. Abbott replied, "I'm not a nice girl. I'm a photographer." Finances presented further obstacles, and she spent her own money on the project until 1935, when the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration began to sponsor her work. Until 1939 she was able to earn a salary of $35 a week and enjoyed the participation of an assistant. When funding ran out, however, she had to abandon the project.

Abbott continued working during the 1940s and 1950s, though largely outside the spotlight. She became preoccupied during this period with scientific photography, hoping to record evidence of the laws of physics and chemistry, among other phenomena. She took courses in chemistry and electricity to expand her understanding. Again her iron determination served her well.

The scientific community looked on her efforts with suspicion, both because of its skepticism about photography's usefulness and its hostility toward women who ventured into the virtually all-male enclave of science. She spent years trying to convince scientists and publishers that texts and journals could be illustrated with photographs, fighting the conventional belief that drawings were sufficient. In all, as Abbott told an interviewer, the project was a minefield of sexism: "When I wanted to do a book on electricity, most scientists … insisted it couldn't be done. When I finally found a collaborator, his wife objected to his working with a woman. … The male lab assistants were treated with more respect than I was. You have no idea what I went through because I was a woman."

Political events rescued Abbott when the Soviet Union launched the first space satellite in 1957, initiating the "space race." The U.S. government began a new push in the field of science. In 1958 Abbott was invited to join the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Physical Science Study Committee, which was charged with the task of improving high school science education. At last Abbott was vindicated in her insistence on the value of photography to science. Her biographer, Hank O'Neal, has said that her scientific photos were her best work. This is a subject of some debate, but many agree that she was able to uniquely demonstrate the beauty and grace in the path of a bouncing ball, the pattern of iron filings around a magnet, or the formation of soap bubbles.

In her later years Abbott did some photography around the country, in particular documenting U.S. Route l, a highway along the East Coast from Florida to Maine. During this project she fell in love with Maine and bought a small house in the woods of that state, where she lived for the rest of her life. As the popularity of photography grew in the 1970s and her life's work became recognized, Abbott was visited there by a string of admirers, photography students, and journalists. She became something of a legend in her own time, honored as a pioneer woman artist who conquered a male-dominated field thanks to "the vinegar of her personality and the iron of her character." But perhaps most importantly, students of the medium recognized the talent and artistry behind Abbot's work, among which reside some of the prize gems of twentieth-century photography.

Abbott, Berenice, Berenice Abbott, Aperture Foundation, 1988.

Abbott, Berenice, Berenice Abbott Photographs, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1990.