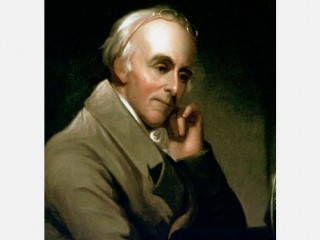

Benjamin Rush biography

Date of birth : 1745-12-24

Date of death : 1813-04-19

Birthplace : Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Nationality : American

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2011-01-05

Credited as : Physician and humanitarian, ,

Benjamin Rush, physician, patriot, and humanitarian, represented the epitome of the versatile, wide-ranging physician in America. He insisted on a theoretical structure for medical practice.

Benjamin Rush was born on Dec. 24, 1745, on a plantation at Byberry near Philadelphia. He graduated in 1760 from the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) and then studied medicine in Philadelphia until 1766. He completed his medical education at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. Here he studied under many of the greatest medical teachers of the time, most notably William Cullen, proponent of the concept of rational rather than empirical medical systems. Rush received his doctorate in 1768, then returned to Philadelphia.

Rush practiced medicine and was soon made the first professor of chemistry in America at the College of Philadelphia. He joined the American Philosophical Society and became a permanent part of Philadelphia's scientific and medical circle, though his outspoken views made as many enemies as friends. In 1774 he helped organize the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and became an outspoken defender of American rights in the brewing quarrel with Great Britain. In 1775 Rush suggested that Thomas Paine write a tract in favor of American independence under the title Common Sense; Paine did and the pamphlet was very influential in turning public opinion toward independence. Rush continued to be active in the American independence movement, was a member of the Continental Congress, and signed the Declaration of Independence.

Appointed surgeon general of the armies of the Middle Department in 1777, Rush found the medical services disorganized and mounted an attack on William Shippen, the director general of medical services. When George Washington upheld Shippen, Rush resigned and resumed his medical practice. He began delivering lectures at the University of the State of Pennsylvania in 1780 and joined the staff of the Pennsylvania Hospital in 1783. By 1789 he was professor of theory and practice in the university. He became professor of the institutes of medicine and clinical practice in the University of Pennsylvania in 1792 and professor of theory and practice in 1796. From this base he developed a wide following.

Rush's great reputation as a teacher made him appear a more important innovator than he was. His major contribution was to introduce Cullen's concept of a rationally deduced medical system to replace empirical folk practice. He also supported the theory of John Brown of Edinburgh proposing a single cause for all disease—imbalance of the nervous energies. According to this theory, all illness was attributable to excesses or deficiencies in nervous energies; moderation in all things was the preventive medicine, but once illness occurred, either bleeding or purging was necessary. Rush was a zealot on bleeding and in extreme cases would remove as much as four-fifths of a patient's blood. His excesses in this brought much criticism, but his emphasis on moderation as a preventive was popular. He was thus led to advocate temperance, and he is sometimes regarded as the founder of the temperance movement in America.

Rush also became interested in the plight of the mentally ill and the poor, established the first free dispensary in the United States, and campaigned against public and capital punishment and for general penal reform. He also concerned himself with education, advocating education for women, less emphasis on classics and more on utilitarian subjects, and a national educational system capped by a national university. His ideas were behind the founding of Dickinson College in 1783.

The test of Rush's medical theories came during the yellow fever epidemic of 1793. His initial theory that the epidemic was partly caused by poor sanitation resulted in ostracism by fellow physicians. Rush bravely stayed in Philadelphia to treat yellow fever victims, while many other medical men fled. His treatment was bleeding, and he was charged with causing many more deaths than he prevented. Although Rush held to his theory, he was either unwilling or simply unable to keep records so that the theory could be checked against fact. However, his published accounts of the epidemic, especially his suggestion that poor sanitation was an ultimate cause, attracted attention in Europe.

Rush also did pioneering work relating dentistry to physiology and was influential in founding veterinary medicine in America. Both fields had been considered beneath the dignity of the professional. His observations on the mentally ill seem to presage modern developments in psychoanalytic theory, especially his Medical Inquiries and Observations on the Diseases of the Mind (1812).

Rush's insistence on a rational, systematic body of knowledge for the medical profession certainly helped set the stage for the later medical revolution in America. He died in Philadelphia on April 19, 1813.

Primary sources on Rush include The Autobiography of Benjamin Rush, edited by George W. Corner (1948); Rush's Letters, edited by L. H. Butterfield (1951); and John A. Schutz and Douglass Adair, eds., The Spur of Fame: Dialogues of John Adams and Benjamin Rush (1966). Although several books have been written about Rush, there is no definitive study. The only fully documented scholarly work is Nathan G. Goodman, Benjamin Rush: Physician and Citizen (1934). Carl A. L. Binger, Revolutionary Doctor: Benjamin Rush (1966), is fairly sound. A popularized work is Sarah R. Riedman and Clarence C. Green, Benjamin Rush (1964). For general background see Daniel J. Boorstin, The Lost World of Thomas Jefferson (1948), and Brooke Hindle, The Pursuit of Science in Revolutionary America, 1735-1789 (1956).

Blinderman, Abraham, Three early champions of education: Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Rush, and Noah Webster, Bloomington, Ind.: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation, 1976.