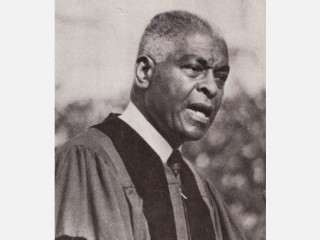

Benjamin E. Mays biography

Date of birth : 1894-08-01

Date of death : 1984-03-28

Birthplace : Greenwood, South Carolina

Nationality : African-American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-12

Credited as : Scholar and educator, minister,

In addition to occupying the president's office at Morehouse, Benjamin Mays wrote, taught mathematics, worked for the Office of Education, served as chairman of the Atlanta Board of Education, preached in a Baptist church, acted as an advisor to the Southern Christian Leadership Council, and was a church historian.

African American scholar Benjamin E. Mays was among the first generation of people of color to be born into freedom in the southern United States. Still, he was forced to battle racial discrimination and economic hardship in the drive to obtain an education. Later, during his 27 years as president of Atlanta's Morehouse College, one of the country's leading black educational institutions, he worked to provide African American students with the academic and social opportunities for which he had fought so hard. Among the many distinguished Morehouse graduates he inspired were former mayor of Atlanta, Andrew Young; Georgia state senator Julian Bond; and civil rights legend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. According to Frank J. Prial of the New York Times, King once described Mays as his "spiritual mentor an…. intellectual father."

During the early 1960s, having entered the third decade of his presidency of Morehouse College, Mays played an important role in the integration of Atlanta by helping students organize sit-ins at lunch counters and other segregated facilities. He later held a prominent position on the Atlanta Board of Education.

Throughout his life, Mays maintained that education, personal pride, and peaceful protest were the most effective weapons in the war against racial bigotry. "To me black power must mean hard work, trained minds, and perfected skills to perform in a competitive society," he wrote in his critically acclaimed autobiography Born to Rebel, published in 1971. "The injustices imposed upon the black man for centuries make it all the more obligatory that he develop himself…. There must be no dichotomy between the development of one's mind and a deep sense of appreciation of one's heritage. An unjust penalty has been imposed upon the Negro because he is black. The dice are loaded against him. Knowing this, as the Jew knows about anti-Semitism, the black man must never forget the necessity that he perfect his talents and potentials to the ultimate."

The youngest of eight children, Benjamin Mays was born in Epworth, South Carolina, in 1894, and raised on an isolated cotton farm. At that time, the maximum school term for black children was only four months—November through February—so he and his brothers and sisters spent most of the year helping with the planting and picking. Mays was an avid student, however; thanks to early lessons from his elder sister, Susie, by the time he arrived at the one-room Brickhouse School at the age of six, he already knew how to count, read, and write. He quickly became the star pupil there and wept whenever bad weather kept him at home.

Church provided another outlet for his talents. At the age of nine he received a standing ovation from the Mount Zion Baptist congregation for his recitation of the Sermon on the Mount. "The people in the church did not contribute one dime to help me with my education," he recalled in Born to Rebel. "But they gave me something far more valuable. They gave me the thing I most needed. They expressed such confidence in me that I always felt that I could never betray their trust, never let them down."

Mays needed all the encouragement he could get. During his childhood, mob violence against blacks was rampant, and brutal lynchings were a common occurrence. Among his earliest memories was that of a group of white men with rifles riding up to his home on horseback and demanding that his father remove his cap and bow down to them. "As a child my life was one of frustration and doubt," he recalled in Born to Rebel. "Nor did the situation improve as I grew older. Long before I could visualize them, I knew within my body, my mind, and my spirit that I faced galling restrictions, seemingly insurmountable barriers, dangers and pitfalls."

When Mays expressed a desire to continue his education beyond the elementary level, his father responded with anger and disdain. At that time, it was believed that the only honest occupations for black men were farming and preaching. Education, his father maintained, made men both liars and fools. Eventually Mays overcame his father's objections, however, and enrolled at the high school of South Carolina State College at Orangeburg. He graduated in 1916 as valedictorian.

Determined to prove his worth in the white man's world, Mays resolved to leave his native South Carolina and continue his education in New England. "How could I know I was not inferior to the white man, having never had a chance to compete with him?" he wrote in Born to Rebel. Mays spent a year at Virginia Union University and obtained letters of recommendation from two of his professors before gaining admission to Bates College in Maine. He began his studies there as a sophomore in September 1917. Summer work as a Pullman porter—as well as scholarships and loans from the college—helped him pay his way.

At Bates, where he was one of only a handful of black students, Mays was surprised and heartened to find himself treated as an equal for the very first time. Both his academic gifts and his enthusiastic participation in extracurricular activities quickly made him a campus leader. After graduating with honors in 1920, Mays completed several semesters of graduate work at the University of Chicago. He then accepted an invitation from Morehouse College president John Hope (whom he happened to meet in the University of Chicago library) to teach higher mathematics in Atlanta. He arrived at Morehouse in 1921, and remained there for the next three years, teaching math, psychology, and religious education. In 1922 he was ordained a Baptist minister and assumed the pastorate of nearby Shiloh Baptist Church. He returned to the University of Chicago in 1924 to complete work on his master's degree, and ten years later received his doctorate in ethics and Christian theology.

Mays's positive experiences as a student at Bates College had filled him with a new sense of pride and optimism. But the Atlanta he encountered in the early 1920s was a tense and angry place, where streetcars, elevators, parks, waiting rooms, and even ambulances were segregated; where Ku Klux Klan rallies and lynchings were everyday facts of life; where people of color were prohibited from voting; and where the only high school education available for African Americans was provided by private academies connected to the all-black colleges. The return of black soldiers from Europe at the end of World War I had only served to heighten racial tensions in the city. "It was in Atlanta, Georgia, that I was to see the race problem in greater depth, and observe and experience it in larger dimensions," Mays wrote in Born to Rebel." It was in Atlanta that I was to find that the cruel tentacles of race prejudice reached out to invade and distort every aspect of Southern life."

After completing his master's degree at the University of Chicago in 1925, Mays spent a year teaching English at the State College of South Carolina at Orangeburg. The following year, he and his wife, Sadie Grey, a teacher and social worker whom he had met in Chicago, moved to Florida, where Mays took over the position of executive secretary for the Tampa Urban League. Two years later, he was named national student secretary of the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA), based in Atlanta.

In 1930 Mays left this post to direct a study of black churches in the United States for the Institute of Social and Religious Research in New York City. He and a fellow minister, Joseph W. Nicholson, spent 14 months collecting data from some 800 rural and urban churches throughout the country in an effort to identify the church's influence in the black community. Among the subjects addressed were the education and training of ministers, the churches' financial resources, and the kinds of religious and social programs offered. The results of the study were published in 1933 under the title The Negro's Church. In a review for the periodical Books, NAACP executive secretary Walter White described the report as "one of the few examinations of this sort" and "an important achievement in its understanding of all the social, economic and other forces which have made [the black church] what it is."

Mays would focus on the vital importance of the black church in American society in a host of other writings published in the 1930s and 1940s. In an article appearing in the summer 1940 issue of Christendom, he maintained that the black church was largely responsible for "keeping one-tenth of America's population sanely religious in the midst of an environment that is, for the most part, hostile to it."

In 1934 Mays became dean of the School of Religion at Howard University. During his six-year tenure, he succeeded in strengthening the faculty and facilities to such an extent that the school achieved a Class A rating from the American Association of Theological Schools. This made it only the second all-black seminary in the nation to receive such accreditation. During this period, Mays traveled widely, attending church and YMCA conferences around the world and earning an international reputation for academic excellence. His wife, Sadie, accompanied him on most of his trips.

Mays was named president of Morehouse College in July of 1940, exactly 19 years after he had begun his teaching career there. In Born to Rebel, published some 30 years later, he reflected upon the ineffable energy and spirit of the place. "I found a special, intangible something at Morehouse in 1921 which sent men out into life with a sense of mission, believing that they could accomplish whatever they set out to do," he wrote. "This priceless quality was still alive when I returned in 1940, and for twenty-seven years I built on what I found, instilling in Morehouse students the idea that despite crippling circumscriptions the sky was their limit."

While president of Morehouse, Mays fought for the integration of all-white colleges but remained an outspoken advocate of predominantly black institutions, such as Morehouse and Howard. "If white America really wants to improve Negro higher education, it would do well to recognize the fact that it will not be adequately done by allowing black colleges to die the slow death of starvation," he wrote in Born to Rebel. His steadfast devotion to academic excellence helped Morehouse become one of only four Georgia colleges to be approved for a chapter of the Phi Beta Kappa honor society.

Perhaps Mays's greatest influence was on the individual students he encountered both in the classroom and through the college chapel. His greatest honor, he later said, was having taught and inspired Martin Luther King, Jr., the college's most celebrated alumnus. During Morehouse commencement ceremonies in June of 1957, Mays honored Dr. King for his leadership in the 1956 Montgomery Bus Boycott by conferring upon him the honorary degree of Doctor of Humane Letters. King later became a member of the Morehouse College board of trustees. Mays also convinced two of Georgia's brightest African American politicians, Andrew Young and Julian Bond, to seek public office.

Mays became even more directly involved in the civil rights movement in 1960 when he agreed to help students from Morehouse and other Atlanta colleges organize peaceful protests throughout the city—an action which, after 18 months, resulted in the integration of the Atlanta public school system. Prial remembered Mays in a New York Times obituary as "a voice of moderation in the critical years of the civil rights movement. He attacked white liberals who paid only lip service to racial equality, but he [also] criticize…. black extremists" for undermining attempts at unity between races.

After his retirement from Morehouse College in 1967, Mays served as a consultant for a variety of governmental, educational, civic, and religious organizations, and in 1969 he became a member of the Atlanta Board of Education. He remained on the board until 1981. During this time he also produced his powerful autobiography, Born to Rebel. In his preface, Mays described the book as "the story of the lifelong quest of a man who desired to be looked upon first as a human being and incidentally as a Negro, to be accepted first as an American and secondarily as a black man." J. B. Cullen of Books called it a "condemnation of the white treatment of the blacks in the United States" and "a story that should be read by everyone." Prior to his death in 1984 at the age of 89, Mays wrote dozens of scholarly articles on racial, educational, and religious issues, spoke at more than 200 universities and colleges, and received some 45 honorary degrees.