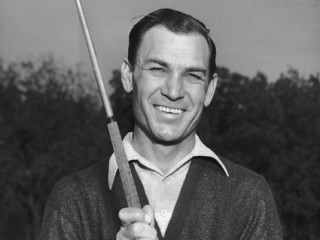

Ben Hogan biography

Date of birth : 1912-04-12

Date of death : 1997-07-30

Birthplace : Dublin, Texas, U.S.

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2011-01-13

Credited as : Professional golfer, in U.S. Open, won the Grand Slam

Frequently revered, yet often misunderstood, Ben Hogan carried a mystique and popularity in golfing circles experienced by few others. He became a phenomenon in the 1940s and 1950s, taking considerable numbers of Professional Golfers Association (PGA) events. Hogan gained a reputation for hard work and excellence both on the links and off.

Ben Hogan was born in Dublin, Texas, on August 13, 1912, to Chester and Clara Hogan. Hogan's father, a blacksmith, took his own life when Ben was nine. His mother moved the family to Fort Worth shortly after her husband died. Hogan went to Fort Worth schools but never finished high school, opting for work instead. He sold newspapers at the train station and would caddy at Glen Gardens Country Club in Fort Worth whenever he could get the work. Jerry Potter, writing for USA Today, said that sometimes Hogan would save two newspapers and make a bed in the bunker near the 18th green. He would sleep there, so he would be first in the caddie line the next morning.

Potter quoted former PGA Tour player Gardner Dickinson, a Hogan student: "Ben was a little bitty fellow, so they'd throw him to the back of the line," Dickinson said. "That's how he got so mean." While some would call Hogan mean, others would say he just kept to himself. There is no question that, while polite on the course, Hogan was often brusque at other times, developing an enduring reputation as a tight-lipped competitor. It could be argued that his demeanor simply illustrated his penchant for action instead of words. Hogan was certainly not a natural when it came to golf. He would diligently work on his game, striving for perfection.

There could be only one reason for Hogan's perseverance: he loved the game. In 1929, 17-year-old Hogan turned pro and began playing in PGA tournaments full time two years later with little more than pocket change. According to Potter, his early efforts were totally frustrating. "He had a long, loose swing that produced shots that were wild," explained Potter. "First he hit a big hook, then he hit a big slice." Hogan would not win a PGA tour event until 1938, seven years after turning pro.

In 1931 and again in 1937, Hogan attempted major tournaments without success. John Omicinski, writing for Gannett News Service, said that Hogan's game did not improve until he switched from a right-handed to a left-handed swing in the late 1930s and got "some rather simple grip tips from friend Henry Picard." He then "lost his duckhook and start smashing shots of such purity that people came from miles around just to watch them fly."

In 1937, Hogan and his wife, Valerie (whom he married in 1935), were down to their last $5 when he won $380 at the PGA tournament in Oakland, California. Although he only placed second, it was the incentive Hogan needed to keep at his game. Asked why he worked so hard, Hogan once explained to Potter: "I was trying to make a living. I'd failed twice to make the Tour. I had to learn to beat the people I was playing." Hogan claimed he never had a golf lesson, instead learning everything he could be watching experienced golfers at their game. "I watched the way they swung the club, the way they hit the ball," Hogan explained to Potter. Hard work on the practice green has become commonplace in a touring pro's regime, but it was unheard of in Hogan's day.

Hogan was the leader on the money boards in 1940, winning the PGA's Harry Vardon trophy for his $10,656 income that year. Between 1939 and 1941 he finished in the money in 56 consecutive tournaments. In the PGA Oakland Open in 1941 Hogan tied the course record at the time with a 62. He was leader on the money board again in 1941 and in 1942, but had a two-year break from golf when he was inducted into the Army Air Force in 1943.

Hogan came on strong after his release from the Army. Some of his earliest wins after returning stateside were paid in war bonds. Hogan had a bout with influenza, however, that set him back, and he suffered through a serious putting slump. Jamie Diaz, writing in Sports Illustrated, said, "In 1946, Hogan suffered what some consider to be the most devastating back-to-back losses in major championship history. At the Masters, he had an 18-foot putt to win his first major PGA tournament. Hogan ran his first putt three feet past the hole, then missed coming back. Two months later at the U.S. Open at Canterbury in Cleveland, he was in an identical situation on the final green. Hogan three-putted again. Instead of ending his career, Hogan went on to the PGA Championship at Portland Golf Club and won, beginning his never-equaled hot streak in the majors."

Hogan was again the top money winner in 1946, and two years later became the first golfer to win three majors in the same year: the Western Open, the National Open, and the U.S. Open. He had finally hit his stride. Hogan would win nine of the 16 majors he entered from the 1946 PGA through the 1953 British Open. Still, Diaz claimed, "because of his inscrutable manner, there was always a sense that he carried something deep within that was even more interesting than his talent."

Perhaps it was Hogan's equanimity in defeat that so impressed the gallery. He possessed a grace and resilience that are emulated by many even today. Or perhaps it was his childhood poverty and his diligent effort to master his game that served to strengthen his character and his resolve. One of his most challenging bouts with adversity came early in 1949, a year that had started with Hogan winning two of the first four events of the season. On February 2, while he and his wife were driving his Cadillac back to Fort Worth, Hogan was hit head-on by a Greyhound bus. To protect his wife, Hogan threw his body over to the right, avoiding the steering column that could have easily crushed him. Instead, he suffered such severe injuries that doctors predicted he would never walk again. Hogan had another near brush with death before surgeons operated to stop blood clots from entering his heart.

Hogan not only taught himself to walk again, he also taught himself to play golf again. In rehabilitation treatment for ten months, some have claimed that Hogan practiced his swing until his hands bled. A mere 16 months after the head-on collision, Hogan walked through excruciating leg cramps to win the U.S. Open at Merion. As a testament to his dogged determination, Hogan was named Player of the Year in 1950. Sam Snead had earned the money title, won 11 events, and set a scoring-average record that clearly entitled him to the honor. But according to Diaz, "Snead was a golfer, and a great one. Hogan, because of his dedication and courage, was a hero."

His fabulous on-the-course performances coupled with his silent, often aloof behavior created a mystique around Hogan that lives on today. He was often portrayed as stoic and severe, even downright rude by some. But Hogan actually preferred his actions to speak louder than his words. Often cutting young golfers off before they could complete a sentence, he would refer those seeking tips to one of his books. Hogan was always the consummate professional, never showing emotion on the course or suffering from distraction. His unwavering focus and ability to place the ball precisely where he intended contributed to the almost eerie presence he brought to the greens.

There are countless stories of his kindness to kids, his affability with some reporters, and his integrity and personal code of honor. Some say the harrowing experience of actually witnessing his father's suicide deeply impacted Hogan's ability to get close to people. Even players like Byron Nelson, who drove with Hogan to tournaments and grew up with him in Fort Worth, would say that they had a hard time keeping in touch. But his regard and admiration for his wife was widely known. Hogan's reputation as a superb athlete and the mystery of his subdued persona made him appealing to the masses. In 1951, Glenn Ford stared in Follow the Sun, a biographical film about Hogan and his wife.

Hogan won six major championships after his car accident. In 1948, his book, Power Golf, a collection of golf do's and don'ts, was published; it was followed in 1957 by the best-selling Five Lessons: The Modern Fundamentals of Golf, co-authored with Herbert Warren Wind. In 1953, he won the Masters, U.S. Open, and British Open-returning to New York City for a ticker-tape parade. The same year, he started the Ben Hogan Co., a golf club manufacturing business.

Despite his success, the auto accident had made walking the courses particularly difficult for Hogan. Although he limited himself to seven tournaments a year since the accident, chronic pain would impede his future golf efforts. After his win in the 1953 British Open at Carnoustie, Diaz notes that Hogan "endured bitter disappointment in pursuit of a record fifth U.S. Open title."

Hogan's final PGA title victory came at the 1959 Colonial Open. In 1960, Hogan sold his golf-club company to AMF. According to Ron Sirak of the Associated Press, Hogan "tied for the lead in the 1960 U.S. Open until, gambling for the pin, he hit a ball that spun backward off the green and into the water on the next-to-last hole. Arnold Palmer won the tournament, with 20-year-old Jack Nicklaus finishing second. Hogan had passed the title of Greatest in the Game to a new generation."

Hogan became even more reclusive in his later years, and was rarely seen in public after his last PGA event in 1971. He retired to his hometown of Fort Worth, where the Colonial Country Club still bears a statue of his likeness at the entry plaza. Hospitalized for two months with pneumonia in 1987, Hogan dropped 30 of his scant 140 pounds. In 1995, he underwent emergency surgery for colon cancer and never really regained his previous vigor. His wife remained his constant companion and caregiver, even after Hogan was diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease. Hogan died on July 25, 1997 in Fort Worth, Texas, after suffering a major stroke. He was 84 years old.

With 63 victories, nine major championships, four U.S. Open titles, the career Grand Slam, and the winner of three professional Grand Slam events in a single season, Hogan enjoyed a stellar professional career that spanned five decades. Before Hogan there was little concept of the driving range. But Hogan's dedication to practice changed all that. He epitomized determination and courage. Although the game has moved on, Hogan's reputation for perfection and perseverance remains.

Dallas Morning News, November 6, 1998.

Detroit News, July 30, 1997.