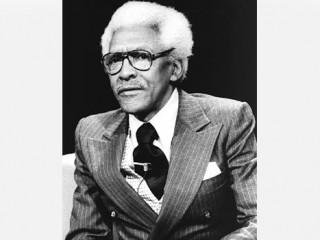

Bayard Rustin biography

Date of birth : 1910-03-17

Date of death : 1987-08-24

Birthplace : West Chester, Pennsylvania, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-08-27

Credited as : Writer, civil rights activist, Liberty Bell Award 1967

1 votes so far

"Sidelights"

The late Bayard Rustin enjoyed a long and distinguished career as a civil rights activist. Beginning in the 1930s as an organizer for the American Communist Party's youth group, continuing as head of the pacifist War Resisters' League and as special assistant to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Rustin ended his career by serving as president and chair of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, an organization promoting civil rights and a radical restructuring of the nation's economic and social life. Influenced by his Quaker upbringing and the radical politics of the 1930s, Rustin called for a peaceful, nonviolent alteration of society. Eric Pace of the New York Times quoted Rustin listing the principles behind his career: "1. nonviolent tactics; 2. constitutional means; 3. democratic procedures; 4. respect for human personality; 5. a belief that all people are one." J. Y. Smith of the Washington Post characterized Rustin as "one of the great theorists and practitioners of the civil rights movement."

Rustin began his career as an organizer for the Young Communist League, an organization he later said he joined because it seemed to be the only one dedicated to civil rights. His work organizing protest marches and demonstrations for the league during the 1930s served him well in later years with the civil rights protests of the 1960s. Rustin left the Young Communist League in 1941 when he decided that the group's politics were too intolerant. He was, however, to remain a non-Communist socialist for the rest of his life. After leaving the group, Rustin was a co-founder of the Congress for Racial Equality, one of the early civil rights organizations, and worked with the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a Quaker antiwar organization.

During the Second World War, Rustin was imprisoned as a conscientious objector. Following a twenty-eight-month stint in a federal penitentiary, he was released at war's end. He was active during the late 1940s in some of the first freedom rides in the South and was arrested in North Carolina in 1947 for participating in an antisegregation protest. He spent twenty-two days on a chain gang for the offense. His subsequent account of his experience, written for a Baltimore newspaper and reprinted nationwide, resulted two years later in the abolition of chain gangs in North Carolina.

Rustin's strong pacifism led in 1953 to his appointment as executive secretary of the War Resisters' League, one of the country's largest pacifist organizations. In this role he was instrumental in planning a series of antinuclear demonstrations in England and North Africa, including the first annual protest rally of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament. Rustin also played a key role in a San Francisco-to-Moscow Peace Walk in the late 1950s.

While actively engaged in pacifist actions during the late 1950s and early 1960s, Rustin also assisted civil rights activists in their growing struggle. In 1955 he helped Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. organize a bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, and went on to serve as a special assistant to King. Rustin also organized civil rights demonstrations at both the Democratic and Republican conventions in 1960, hoping to pressure the two major parties into support for the movement's aims. In 1963 he played a pivotal role in organizing the massive March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, a civil rights protest drawing some 250,000 demonstrators to the nation's capital. It was, Jacqueline Trescott recounted in the Washington Post, "the single largest civil rights demonstration America has ever seen." It was during the protest that King delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech. The London Times noted that the March on Washington is "regarded by historians of the civil rights movement as the watershed of its campaign in the 1960s, and the chief influence on the civil rights bills of 1964 and 1965."

Rustin was also a leader of other important civil rights actions. In 1964, he organized a boycott of the New York City school system in protest of the school board's reluctance to integrate classrooms. Over 400,000 students participated in the boycott. In 1968, he organized the Poor People's Campaign, which brought thousands of poor blacks and whites to Washington to set up a makeshift "Resurrection City" on the grounds of the Lincoln Memorial. When rioting broke out in the Harlem ghetto, Rustin walked the city streets in an effort to persuade people to stop the fighting, an effort that earned him the label "Uncle Tom" from some blacks. "I'm prepared," Rustin explained to the New York Herald Tribune, "to be a Tom if it's the only way I can save women and children from being shot down in the street."

His resistance to black political violence estranged him from more radical elements of the civil rights movement. And Rustin argued against some of the more radical demands of other black activists as well. When black students demanded that colleges adopt black studies programs, Rustin denounced the idea as "stupid." He called for black history to be taught as an integral part of American history, not as a separate discipline. In the 1970s Rustin came out against racial quotas in employment and education. "I have not run into a single young black who wants something because he is black," Smith quoted Rustin explaining. "He wants to pass the test and meet the standards." Rustin's later support for Jewish issues, his work with refugees from Southeast Asia, and his continued involvement with trade unions spurred criticism from some black leaders who felt Rustin had distanced himself from the civil rights struggle. But Rustin dismissed the criticism. "I can't call on other people continuously to help me and mine," Rustin explained to Trescott, "unless I give indication that I am willing to help other people in trouble."

Rustin's long career on behalf of those in trouble earned him accolades from many quarters. Upon his death in 1987, the Chicago Tribune claimed that "Rustin was committed to the causes in which he believed, but he also followed the path of his reason wherever it led. He did not let his allegiance to the labor movement blind him to the virtues of free trade. He did not let his love for peace blind him to the dangers of expansion-minded dictators. He did not let his love for his own race blind him to the sorrows felt by the rest of the human race. He would not let his skin color get in the way of his conscience."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Family: Born March 17, 1910 (some sources list as 1912), in West Chester, PA; died August 24, 1987, of a heart attack, in New York City; son of Janifer (a caterer) and Julia (a social worker; maiden name, Davis) Rustin. Education: Attended Wilberforce University, 1930-31, Cheyney State Normal School (now Cheyney State College), 1931-33, and City College (now City College of the City University of New York), 1933-35. Politics: Socialist. Religion: Society of Friends (Quaker).

AWARDS

Man of the Year Award, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Pittsburgh branch, 1965; Eleanor Roosevelt Award, Trade Union Leadership Council, 1966; Liberty Bell Award, Howard University Law School, 1967; LL.D. from New School for Social Research, 1968, and Brown University, 1972; Litt.D. from Montclair State College, 1968; John Dewey Award, United Federation of Teachers, 1968; Family of Man Award, National Council of Churches, 1969; John F. Kennedy Award, National Council of Jewish Women, 1971; Lyndon Johnson Award, Urban League, 1974; Murray Green Award, American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFLCIO), 1980; Stephen Wise Award, Jewish Committee, 1981; John La Farge Memorial Award, Catholic Interracial Council of New York, 1981; Defender of Jerusalem Award, Jabotinsky Foundation, 1987; also received honorary degrees from Columbia University, Clark College, Harvard University, New York University, and Yale University.

CAREER

Organizer, Young Communist League, 1936-41; race relations director, Fellowship of Reconciliation, 1941-53; jailed as conscientious objector, 1943-45; executive secretary, War Resisters' League, 1953-64; special assistant to Martin Luther King, Jr., 1955-60; A. Philip Randolph Institute, New York, NY, president, 1966-79, chair, 1979-87. Field secretary and co-founder, Congress for Racial Equality, 1941. Chair of Leadership Conference on Civil Rights and Recruitment and Training Program; co-chair, Social Democrats of the U.S.A.; chair of executive committee, Freedom House. Ratner Lecturer, Columbia University, 1974. Founder, Organization for Black Americans to Support Israel, 1975. Member of boards of directors, Notre Dame University, Metropolitan Applied Research Center, and League for Industrial Democracy. International vice-president, International Rescue Committee.

WRITINGS BY THE AUTHOR

* Down the Line: The Collected Writings of Bayard Rustin, Quadrangle, 1971.

* Strategies for Freedom: The Changing Patterns of Black Protest, Columbia University Press, 1976.

* The Bayard Rustin Papers, University Publications of America, 1988.

Also author of pamphlets and published speeches. Contributor to periodicals. Editor, Liberation (magazine).