Barry Zito biography

Date of birth : 1978-05-13

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Las Vegas, Nevada, USA

Nationality : American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-16

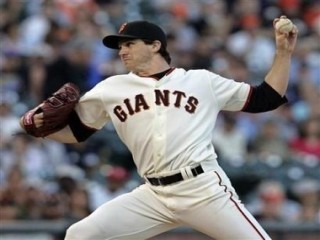

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, pitcher with the San Francisco Giants,

0 votes so far

Barry William Zito was born on May 13, 1978 in Las Vegas, Nevada. He was a late-in-life baby for Roberta and Joe, a show biz couple who met and married while working for Nat King Cole in the 1960s. Joe was Cole’s conductor and arranger, Roberta, a classically trained violinist and pianist, was a singer in the star’s backup group, the Merry Young Souls.

The Zitos were in the making-ends-meet mode by the time Barry arrived. His first instrument was a Cookie Monster drum set, but his interests were already varied. Barry could read at age three—the same year he received a red plastic bat that ignited his passion for baseball. Soon the family’s front hall was a makeshift baseball diamond. In second grade, Barry’s teacher asked her students to draw a picture of what they wanted to do when they grew up. The 7-year-old colored a baseball pitcher and scrawled the words “Make a million dollars” above it.

One thing Barry would never lack in his quest for that first million was a rooting section. Barry likes to say he had three “moms.” There was Roberta, of course, but also two much-older sisters, Sally (already nine when he was born) and Bonnie (13 years his senior). They spoiled him rotten and encouraged any and all of his interests. But in the end it was Barry’s relationship with his father that led him to fully explore his athletic ability.

Though Joe knew nothing of baseball, he could see how serious—and good—his son was when it came to the sport. The solution for the elder Zito was to approach the game as he would any new subject. He read all he could about technique and history and discussed these topics with Barry at length. Talking was a big part of the Zito family culture—acquiring and sharing knowledge was something of an obsession, in fact. Thus as Barry’s physical skills were developing, his mental approach to baseball was already in full bloom.

By his early teens, Barry was excelling as a pitcher. Joe decided to give up his musical career and devote himself to his son. Roberta found a teaching job in San Diego, and the family moved to El Cajon. No one in the family enjoyed their new neighborhood, a washed-out area marked inhabited by tough, blue-collar families.

When Barry’s body began to mature, his father decided it was time to hire a professional coach. For one hour a week, he worked with former Cy Young Award winner Randy Jones, who still lived in the San Diego area. Jones, a supreme tactician during his pitching days, had a unique coaching style. Whenever Barry did something wrong, he would cover the boy’s Nikes with a stream of tobacco juice.

The sessions cost $50, which came out of the family’s already-stretched food budget. Joe and Roberta figured it was a sound investment—they would not be able to afford college tuition for Barry, but he was on track for a baseball scholarship, so the money was well spent.

Under Jones’s tutelage, Barry starred for the Grossmont High School varsity and gained valuable experience pitching in top-tier summer league tournaments. In 1995, he switched to University High—a private school—and earned all-league honors with an 8-4 record, 2.92 ERA and 105 strikeouts in 85 innings. Despite those numbers, he garnered little interest from the top west coast colleges. Barry’s pitching style scared them off. Although he had a devilish curve and an advanced understanding of his craft, he threw across his body, thus cutting the velocity on his fastball, which topped out in the low 80s.

Barry had other interests. San Diego had a serious skateboarding culture in the early 1990s, and he became a part of it. At the same time, he also fooled around with various musical instruments, although none all that seriously.

Barry got three scholarship offers—from Wake Forest, UC Santa Barbara and Cal State Northridge. He was also drafted by the Seattle Mariners, albeit it in the 59th round. M’s scout Craig Weissmann believed Barry could be a special pitcher, but cringed at his mechanics. He worked with Barry on the backyard mound for a few weeks and straightened out his delivery. Suddenly, the ball was popping into Joe’s glove at over 90 mph.

Weismann called the Mariners and told them that they had uncovered a gem—a potential front-line starter for a famously pitching-starved organization. On his word, Seattle tendered Barry a $90,000 bonus offer, which is unheard of for such a low pick. The lefty turned down the deal. He thought he should be a first-round pick.

That summer, Barry began working with Rick Peterson. A pitching coach in the Toronto organization, Peterson had a reputation for thinking outside the box. Joe called him out of the blue and convinced him to meet with Barry. The two hit it off immediately. For Barry, it was like looking at himself 20 years later. He and Peterson talked about everything from the Zen of pitching to Yoga. Peterson told him that success on the mound came down to bridging the gap between potential and performance. This involved three things: solid fundamentals, physical conditioning, and mental discipline.

Barry took this philosophy to heart and decided to go to Santa Barbara. He was now convinced he could work his way to the top of the draft.

ON THE RISE

Santa Barbara was like San Diego without the traffic and the military. When a bunch of his friends asked him if he surfed, he lied and said yeah. He bought his own board and hit the waves 60 days in a row until he could hang a respectable ten. On a visit home, he tried San Diego’s notorious Black Beach when the waves were more than 15 feet high. One near-death experience later he swore off surfing forever ... then was back on the board the very next weekend.

Barry was no less tenacious on the mound. He was named a freshman All-American despite toiling for a sub-.500 team that finished last in the Big West’s southern division. In 1998, Barry transferred to the baseball factory at Pierce Junior College in Los Angeles. He went 9-2 with 135 strikeouts in 103 innings to earn All-State and All-Conference honors. Now recognized as one of the country’s best pitchers, he was offered a full ride at USC.

Barry was also drafted by the Texas Rangers in the third round. It wasn’t the first round, but it was close enough—assuming he got a respectable signing bonus. What he got was a lack of respect. Barry asked for $350,000, which was about right for the 83rd pick. The Rangers were unwilling to go above $300,000. Despite his bargaining history, Ranger execs felt he would come around. They were wrong.

Barry pitched for Wareham in the Cape Cod League over the summer, and then returned to Pierce in the fall to finish up the credits he need to attend Southern Cal. The spring semester found him in a Trojans uniform. The Rangers, like the M’s two years earlier, were left holding an empty bag.

Coming off a national championship, the 1999 Trojans were reloading for a new season. Among the team’s stars were future major league sluggers Jason Lane and Eric Munson, who were replacing 1998 draftees Morgan Ensberg, Robb Gorr and Jeremy Freitas. The trio had accounted for more than 50 home runs the year before. Barry would be asked to fill the shoes of another draftee, Seth Etherton, who had won 13 times in ’98.

Barry answered the call with a 12-3 record and 154 strikeouts in 113 innings of work. A First-Team All-American, he was now viewed as a no-brainer first-round pick. Meanwhile, the Trojans, under Mike Gillespie, finished the ’99 campaign with a somewhat disappointing 33-23 record, but they earned a bid to the NCAA Tournament. After advancing out of its regional round, USC lost to Stanford and was bumped out of the tournament. In the June draft, as he had long hoped, Barry went in the first round to the Oakland A’s, who used the ninth selection on him. Munson, who had a lights-out season, was the #3 pick, by the Detroit Tigers.

Barry signed for a $1.59 million bonus and was assigned to Oakland’s Class-A team in Visalia. He started eight games and went 3-0 with a 2.45 ERA under what turned out to be extremely trying conditions. Barry’s mom developed cirrhosis and had fallen desperately ill that spring. In need of a liver transplant, she was fading fast. He set land speed records driving back and forth from Visalia to Cedar Sinai Hospital in Los Angeles, trying to be with her as much as he could. A matching donor was found in July, and Roberta pulled through.

With family matters under control, Barry began a rapid ascent through the farm system. He was promoted to Midland and went 2-1 to finish the Class-AA schedule, and then got a start at Triple-A Vancouver, striking out six and allowing a lone earned run in six innings. He played a key role in the Canadians’ Pacific Coast League and AAA World Series championships, allowing just four earned runs in two postseason starts. All told, between college and pro ball, Barry’s 1999 record was a remarkable 19-5.

The 2000 season found Barry in the A’s major league camp, mowing down batters and impressing his coaches. Oakland management decided he would begin the season at Sacramento, the new home of the team’s AAA affiliate, and stay there as long as possible before the inevitable call-up. In 18 starts for the RiverCats, Barry went 8-5 with a 3.19 ERA and held batters to a .230 average. There was talk of bringing him up in June, but the team held out until late July.

The A’s were locked in a struggle for their first division title in eight years. Barry joined a rotation led by young guns Mark Mulder and Tim Hudson. Veterans Gil Heredia and Kevin Appier were solid as well. The rookie got his first start against the Angels. He cruised along until the fifth inning, when Anaheim loaded the bases with none out and Mo Vaughn, Tim Salmon and Garrett Anderson due up. Serving up a masterful mix of fastballs and curves, Barry retired all three stars on strikes. The team’s pitching coach knew he had a stud on his hands. His name was Rick Peterson.

Oakland went on to beat the Halos, giving Barry his first major league win. He made 13 more starts for the A’s, finishing with a 7-4 record. His 2.72 ERA was the lowest among all rookies and the best ever for an Oakland newcomer. American League batters mustered just a .195 average against him. With the A’s going down to the wire against the Mariners, Barry posted a 5-1 record in his six September starts—including a shutout against the Tampa Bay Devil Rays. His only loss came when the A’s were blanked by the Baltimore Orioles.

After winning the West, the brash A’s went into the postseason against the battle-hardened New York Yankees. After splitting the first two games of the Divisional Series in Oakland, the teams jetted east to the Bronx for the next two. The Yanks beat Hudson in Game 3, pushing the A’s right to the brink. Manager Art Howe handed the ball to Barry and told him to save the season. The rookie responded by handcuffing New York into the sixth inning, allowing one run on seven hits. His teammates pounded Roger Clemens and three relievers for an 11-1 victory that stunned the home crowd.

With the Yankees forced to return to California for the deciding game, confidence in the Oakland clubhouse was sky-high. But a disastrous first inning in Game 5 sealed Oakland’s fate, and Barry’s fine performance was wasted, as the Yankees prevailed by a score of 7-5.

Needless to say, great things were expected of Barry heading into the 2001 season. The A’s were heavy favorites in the AL West, and they now had the experience to compete in the postseason. Unfortunately, a sluggish spring and a record start by the Mariners combined to eliminate Oakland from the division race by the All-Star break.

Barry was part of the problem. He allowed 25 runs in his first 26 innings, and it didn’t get much better from there. After 22 starts, his record was just 6-7, and his ERA was over 5.00. Instead of getting big outs against opponents, they were getting clutch hits. The low point came during a week that saw him get pounded in back-to-back starts against the lowly Minnesota Twins. Barry was lost, and only one person could help find him.

His dad drove up from Los Angeles and moved in with Barry for the last week of July. For four straight days they did nothing but talk about pitching. Joe brought some of the baseball books the two had read years earlier, and they reread them together. Somewhere during those 96 hours, Barry got back to a place and time when baseball was a simple, easy game. And then he built himself back up.

The change in Barry was astonishing. He was the best pitcher in baseball over the last two months, with an 11-1 record and 1.32 ERA. He reeled off nine straight victories to finish the season, and the A’s ended up with 102 wins and a Wild Card berth. Barry’s final numbers were good, yet they barely hinted at how well he threw. His record stood at 17-8 with a 3.49 ERA and 205 strikeouts.

Barry’s great pitching continued in the playoffs, once again against the Yankees. This time, he got the ball in Game 3 with a chance to close out New York, which had dropped the first two contests. Barry dazzled the Yanks, allowing just two hits and striking out six in eight masterful innings. His lone mistake was a fat pitch to Jorge Posada that he hammered for a solo home run. Unfortunately for the A’s, it was the only run of the game. Oakland failed to score against Mike Mussina and lost 1-0. The Yankees took the next two games from the stunned A’s and left them on the outside looking in for the second October in a row.

That winter, Barry returned to his Hollywood apartment, switched agents, and began courting the media. Already known as a quote machine, he granted the press unfettered access to the inner workings of his mind. During an unforgettable hourlong appearance on Jim Rome’s “The Last Word,” he shot the breeze, played some guitar and completely disarmed the heavily armed talkshow host. Barry also replaced Hudson as the team’s player rep, after the birth of Hudson’s daughter. He actually enjoyed the conference calls and strategy meetings, especially with a complex and interesting topic like contraction on the table.

The A’s broke camp in 2002 minus three key contributors. Jason Giambi, closer Jason Isringhausen and leadoff hitter Johnny Damon all flew the coop via free agency. The A’s acquired Toronto’s Billy Koch as a stopgap closer and replaced the missing bats with solid situational hitters. Shortstop Miguel Tejada and third baseman Eric Chavez blossomed into MVP-caliber performers, and the starters hit their collective stride by June. Although Seattle started hot again, the Mariners could not maintain the previous year’s torrid pace. Oakland hung close and by early August were within striking range of the M’s and the resurgent Angels.

MAKING HIS MARK

To a great degree, Barry’s season mirrored his team’s. He did not win until his sixth start and did not get his record above .500 until mid May. From then until the end of the year, however, he was magical. During one six-week period, he was 9-0 and reached double-digits in strikeouts twice. After a June loss to the Mariners, Barry went 5-0 in July and appeared in his first All-Star Game.

Barry was beaten in his first two August starts but was perfect the rest of the way, winning eight straight to finish 23-5. During that time the A’s went on a winning streak of their own, capturing a league-record 20 straight victories. Oakland then prevailed in a tight duel with the Angels for the division crown.

Winning the AL West meant the A’s did not have to deal with the Yankees in the first round. Instead, they played the overachieving Twins, champions of the Central Division. After clinching the division on September 26, Howe set up his playoff rotation. Hudson and Mulder would start the first two games against the Twins in Oakland. Barry—who historically had trouble with Minnesota—would go in Game 3.

The A’s were heavy favorites, but the pesky Twins took Game 1 when the Oakland bullpen failed to hold a big lead. Mulder pitched a gem in Game 2, and then Barry followed with a nice outing to give the A’s a 2-1 lead and control of the series. The tables turned, however, when Hudson threw poorly in Game 4 and the Twins won 11-2. The decisive fifth game began as a pitching duel between Mulder and Brad Radke, but it slipped away when Koch came on and gave up three late runs. Once again, the A’s made a first-round exit. Ironically, the Angels defeated the Yankees, and then beat the Twins and Giants to win the championship. To a man, the A’s felt that title should have been theirs.

Barry capped off his great season with the Cy Young Award, which he won over Pedro Martinez. The seventh-youngest pitcher to earn the trophy, he was the first of Oakland’s Big Three to cop the award. In 2000, many felt Hudson should have won; ditto for Mulder in 2001.

For the A’s, the 2002 offseason brought more defections. Most notably, Howe left for the New York Mets and was replaced by Ken Macha. Also, Koch was traded away to the White Sox, with Keith Foulke brought in to the take over the closing duties.

By now, Oakland fans had gotten used to these December panic attacks. As a small-market club, they knew the drill. But they also were secure in the fact that they still had a competitive team to root for. With Barry and the other two aces, the A’s still had pitching. Meanwhile, budding superstars like Tejada and Chavez gave them enough solid bats. And with a crafty GM like Billy Beane, somehow they figured to get the right mix of players come crunch time.

Early in the 2003 campaign, however, Oakland slumped. Tejada was the main culprit. In the walk-year of his contract, he pressed at the plate, the thought of showcasing his skills for potential suitors apparently getting the best of him.

Barry, by contrast, didn’t skip a beat from his Cy Young season. Through the year’s first two months, he went 6-4 with an ERA under 3.00. Though his numbers fell off in June, he was still chosen by Anaheim skipper Mike Scioscia for the AL All-Star team. But, in a strange series of events, Barry was yanked off the squad. With the Commissioner’s office looking for a way to add Roger Clemens to the roster, a decision was made to give him Barry’s spot. The problem was that fans and the media found out about the move before the lefty did. Barry handled the situation like a consummate pro, understanding why baseball wanted Clemens to pitch once more in the Mid-Summer Classic and not raising a big fuss about it.

As they normally do, the A’s heated up heading into August. In the blink of an eye, they passed the Mariners for first in the AL West. Even an injury to Mulder didn’t slow down the team. By then, Tejada had regained his stroke, Beane had acquired a much-needed bat in the form of Jose Guillen, and the pitching staff was rounding into shape as a whole. Barry was working out some kinks, too. Though he struggled at times with his command and lost his rhythm, he came through with clutch starts down the stretch to help Oakland secure the division title.

In the first round of the playoffs, the A’s were matched against the mighty Boston Red Sox. Oakland drew first blood, seizing a 2-0 series lead behind solid pitching and timely hitting. Barry pitched in Game 2 and baffled the Red Sox for seven masterful innings. Heading to Beantown, the A’s looked to be in total control. But a pair of painfully weird losses by Oakland turned the ALDS around. In both defeats, the A’s bungled routine defensive plays and committed egregious baserunning blunders to keep Boston alive.

In Game 5, Barry squared off against Pedro Martinez on three days rest. After cruising through the first five innings, he began to tire, surrendering four runs in the sixth. That one bad stanza proved to be the difference. Though the A’s loaded the bases in the ninth, they couldn’t push across the tying run and fell 4-3.

Afterward, Barry and his teammates were left to ponder their collapse. No team in recent history has had more difficulty closing out playoff series. Why Oakland failed again in the postseason was a mystery. Even Beane, one of the game’s brightest minds, couldn’t figure it out.

That being said, the Oakland GM knew his pitching staff was set. With three dominant starters—any of whom would be the ace in another rotation—the A’s figured to remain a pennant contender. While young Rich Harden hoped to give the team a fourth #1 starter, the weight of winning still fell directly on the trio’s shoulders.

Barry understood this dynamic and seemed to revel in the challenge. Thanks to his Cy Young award, he was forced to deal with new pressures during the ‘03 campaign. Though he slumped at times on the mound, he received passing marks overall for his follow-up season, which read 14-12 with a 3.30 ERA.

Entering the 2004 season, the question on everyone's mind was whether Barry could regain his Cy Young form without his longtime pitching coach Rick Peterson, who joined his former boss Howe, in New York with the Mets. Peterson had received a lot of the behind-the-scenes credit for the success of Barry, Mulder and Hudson. All three were eager to prove they could thrive on their own.

Barry looked terrific in his first start of the year, going eight strong innings in Texas. Though the A's lost 2-1, the outing was a good sign for the lefty. A week later, however, the Rangers battered him around in Oakland. But the club—minus Tejada, who had signed as a free agent with Baltimore—surprised with an offensive barrage of its own to hand Barry his first win on the young campaign.

It was more of the same as the season moved towards the All-Star break. Struggling with his command, Barry couldn't get himself on track. His record stood at 4-7, and trade rumors circulated that he was headed to any number of teams, including the Mets, who were in the market for a top-of-the-rotation arm. With the lefty due a pay raise in 2005, the A's didn't do much to contain the speculation.

Barry showed signs of rebounding in July, winning his last three starts of the month. With the race in the AL West heating up, Oakland was thrilled to see the improvement. Anaheim and Texas were each poised to make a run, and the A's looked to their veteran staff for help. Ironically, however, it was Harden who logged the most consistent innings.

The A’s struggled down the stretch, but they remained in the thick of things. As the campaign's final weekend approached, Oakland was tied with the Angels. With the teams scheduled to square off in a three-game series, the A's needed two victories to move on to the playoffs. When Anaheim blasted Mulder on Friday night, all the pressure shifted to Barry. He came up big, throwing seven innings of three-hit ball and leaving with a 4-2 lead. But the bullpen collapsed in the eighth, and Oakland was eliminated from the postseason picture.

For Barry, the '04 campaign raised more questions than it answered. At 11-11 with a 4.48 ERA, hescuffled through the worst season of his career. Every now and then, he flashed his Cy Young stuff, but more often than not he fizzled. To his credit, he took the ball every time his number was called and didn't try to hide from the media.

Barry upped his victory total to 14 in 2005, but lost a career-high 13. He had an up and down season, with the biggest up in July, when he went 6–0. Barry’s biggest down was April, when he failed to win a game.

The A’s chased the Angels most of the year, and then lost them in September, finishing with 88 wins, six games out of the AL West and seven out of the Wild Card.

In 2006, Barry pitched the entire year for the A’s amidst rumors that the team was trying to trade him. In the final year of his contract, Oakland admitted it held out no hope of resigning him. As the trade deadline approached, the Mets made a big push for Barry, hoping to beef up their aging staff for the postseason. But New York would not give up Lastings Milledge and Aaron Heilman, the players Oakland wanted. Barry wound up the season in green and gold, with 16 victories—his best total since 2002—and a 3.83 ERA. The A’s, powered by Frank Thomas and Nick Swisher, won the West, fnishing four games ahead of the Angels.

Barry got the ball for the opening game of the Division Series and outpitched Johan Santana of the Twins in a marvelous duel that ended in Oakland’s favor, 3–2. The victory triggered a three-game sweep that sent the A’s to the ALCS, with yet another chance to win the pennant.

Alas, it was not to be. Barry was chased in the fourth inning of his start against the Tigers, who went on to win the game and the series, denying Oakland a chance to reach the World Series.

After the season, Barry sat back and enjoyed a bidding war orchestrated by his new agent, Scott Boras. Among the teams vying for his services were the Mets, Rangers, Mariners, and Giants. San Francisco prevailed, inking him for seven years at $128 million.

Adjusting to a new team, league and ballpark was much more of a challenge than Barry anticipated. He never found his rhythm in 2007, winning 11 and losing 15 with an inflated ERA of 4.53. He was up and down all year. Barry yielded eight earned runs in his second start and followed that with two scoreless outings. When he did pitch well, the Giants often failed to score for him. It was a horrible season. From 76 wins in 2006, the Giants finished five games worse in ’07in the NL West cellar.

Incredibly, the 2008 season was an even bigger disaster for Barry. He was supposed to be the veteran leader of staff that featured 20-something up-and-comers Tim Lincecum, Matt Cain and Jonathan Sanchez. Instead, he went 10–17 with an ERA over 5.00. His 17 defeats were the most in the league. Barry’s season began with six straight losses, making him only the third pitcher since 1956 to go 0–6 in April. Manager Bruce Bochy yanked him from the rotation for the first time in his career.

Barry had lost a little off his fastball as many pitchers do entering their 30s. Now, instead of challenging hitters, he had become a nibbler. He had a terrible time getting ahead of hitters, and his walks skyrocketed.

Things improved in 2009 when Barry began to change his pitching style, lowering his release point to gain more velocity on his fastball and mixing his slider in more often. This seemed to help him regain command of his curveball, which had been unreliable from start to start in his first two years with the club. Although his record was only 10–13, he suffered from the second-worst run support in the league. He had actually pitched very well most of the season.

Run support looked like it would be a problem again heading into 2010. The San Francisco offense featured Pablo Sandoval, Benji Molina and not much else. The Giants weren’t sure what to expect from newcomer Aubrey Huff, and young phenom Buster Posey appeared a year away from stardom. Pitching would have to get San Francisco through the rough patches. The Giants had a lights-out starting rotation headed by the now two-time Cy Young Award winner Lincecum. San Francisco also had a dominant closer in Brian Wilson.

By midseason, Sandoval was playing his way onto the bench, and Molina was on the trading block. But they were picked up by journeymen like Andres Torres, Pat Burrell, and Juan Uribe. Meanwhile, Huff was having a sensational season, and Posey had joined the club and was hitting like a Triple Crown threat. The Giants were in the hunt all summer, lurking a few games back of the overachieving Padres.

For a while, Barry looked like he had turned his luck around. In fact, he might have been the best starter in the rotation. His record stood at 7–2 after 10 weeks, with an ERA around 3.00. Giants fans knew him to be a good second-half pitcher, so there was a lot of excitement about what his final numbers might be. Unfortunately, he won just twice more—once in July and once in September. He turned in some quality starts in his losses and no-decisions, but he was not an asset for the club down the stretch. He finished 9–14 with a 4.14 ERA.

The Giants still managed to squeak past San Diego to take the NL West crown. As his teammates tore through the postseason on their way to an unlikely World Series championship, Barry found himself in the unfamiliar role of spectator. The Giants only needed four starters and left him off the postseason roster in favor of Madison Bumgarner.

With Bumgarner likely to earn the fourth starter’s job in 2011, Barry’s days as a 30-start hurler may be numbered, at least in San Francisco. But it may not be smart to count him out. Plenty of lefties have found new life late in their careers, from Tom Glavine to Jamie Moyer. Like Moyer, Zito has said he plans to pitch into his mid-40s. Barry certainly has the pitches to be a big winner again. He just needs to find the winning combination.

What else goes on in that head of his is anyone’s guess. Which, of course, is just the way Barry likes it.

BARRY THE PLAYER

Although Barry isn’t the hardest thrower in baseball, he is capable of hitting the low 90s when he rears back and fires the ball. His comfort zone—and control—is in the mid 80s. When you have one of the best curves in baseball, that’s fast enough.

When Barry doesn’t have his curve working, it becomes a battle of wits with the hitters. Needless to say, he is well equipped in this department. He relies on his fastball, though he no longer has the pinpoint control that turned him into an All-Star with the A’s.

Surviving with his second-best pitch has become easier as his slider and changeup have developed. Barry will throw them to anyone at any time, and that adds an extra foot to his fastball. A key to his success will be the fact that he still delivers all of his pitches from the same spot, with the same arm speed.