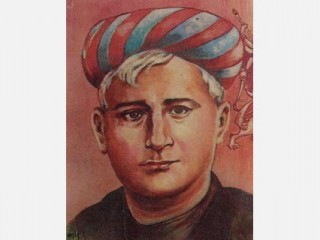

Bankimchandra Chatterji biography

Date of birth : 1838-06-26

Date of death : 1894-04-08

Birthplace : Kanthalpara, near Calcutta, India

Nationality : Indian

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2011-01-04

Credited as : Writer , Bengali novelist - Western,

The Bengali novelist Bankimchandra Chatterji was the first writer to use the Western form of the novel successfully in an Indian language.

Bankimchandra Chatterji was born on June 26, 1838, in the village of Kanthalpara near Calcutta. His father, Jadavchandra, an orthodox Kulin Brahmin, was a deputy collector of revenues. Bankimchandra received much of his early traditional Hindu education from a family priest. He was married at the age of 11 to a girl of 5 and in the same year, 1849, was enrolled in Hooghly College.

At Hooghly College, and later at Presidency College, Calcutta, Bankimchandra's education became almost entirely Western, with an emphasis on science, history, language, law, and philosophy. In 1858 he became one of the first two students to earn a baccalaureate from newly founded Calcutta University. Immediately after graduation he was appointed a deputy collector by the British colonial government and remained in that position without promotion for 33 years. He retired in 1891. But while he was a government official, he began to write novels in his spare time. He is said to have suffered from diabetes for some years, and he died 2 years after his retirement, on April 8, 1894.

Bankimchandra wrote his first novel, Rajmohan's Wife (1864), in English. Thereafter he wrote 14 novels in Bengali from 1865 to 1884. He combined Sanskritized and colloquial Bengali in a manner that made it for the first time an adequate vehicle for expressing a wide range of subjects that hitherto had had to be stated in Sanskrit or English. His first Bengali novel, Durgeshnandini (1865), is said to have created a sensation in Calcutta. Bengalis had read English novelists, like Sir Walter Scott, but Bankimchandra's novels were the first that gave them a satisfying semblance of their own world in fictional form. His first three novels were pure romance decked out in historical costume. While the history in these and in later novels with historical themes was often inaccurate, the bravery of the heroes and the beauty, endurance, and self-sacrifice of the heroines served to inspire Bengalis with notions of a glorious past.

In his social novels Bankimchandra was bold for his time in creating characters who broke with traditional codes of behavior, but he was careful to see that in the end the conventional prevailed over the unconventional. In his two best social novels, Vishavriksha (1873) and Krishnakanter Will (1878), he explores the questions of extramarital love and remarriage of widows, but by means of suicide and murder he clears the way for convention to win out. He was guilty of helping the right as he saw it to overcome the wrong by undisguised authorial intervention in the affairs of his characters. However, Bankimchandra's works possessed vitality. In the numerous, short chapters, dramatic events happened frequently, humor appeared everywhere, and there was movement, action, and feeling. Many of the names of his fictional characters have passed into the idiom of the language.

Bankimchandra became an adult at a time when the educated people of Bengal were beginning seriously to reexamine their ideals. The easy acceptance of everything Western and the derogation of everything Hindu had by this time given rise to a strong Hindu reaction. Bankimchandra became a spokesman for the orthodox point of view. He wrote a book on the Lord Krishna which showed a personal God with attributes more lofty than those of the Christian God. Bankimchandra defended the institution of caste, though he acknowledged some of its evils. In one of his last novels, Anandamath, he described a strongly disciplined order of sanyasis who revolted against the medieval Moslem rulers of Bengal. These sanyasis worshiped the mother-goddess Durga, who became to Bengali readers a powerful symbol of religion and patriotism. A long poem in this book, Bande Mataram (Hail to the Mother), became after Bankimchandra's death the anthem of Hindu nationalists in the early 20th century.

Bankimchandra's impact on nationalist thought and action was based on his teaching of a renewed faith in Hinduism, and occasionally this was used to exacerbate communal antagonism between Hindus and Moslems. Though he proposed no specific plan for gaining independence or for governing the country after independence, his ideas blossomed in other men's minds and were a force in the Indian nationalist movement.

Most of Bankimchandra's novels have been translated into English. Biographical and critical works on Bankimchandra in English are generally uninspiring. Jayanta-Kumara Dasa Gupta, A Critical Study of the Life and Novels of Bankimcandra … (1937), is readily available in university libraries. More enjoyable to read and more detailed biographically, although undocumented and marred by faulty English, is Mati-Lala Dasa, Bankim Chandra, Prophet of the Indian Renaissance: His Life and Art (1938).

Bose, Sunil Kumar, Bankim Chandra Chatterji, New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Govt. of India, 1974.