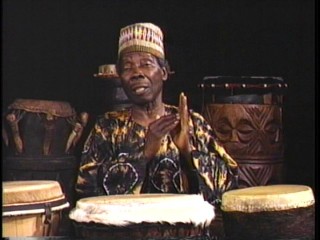

Babatunde Olatunji biography

Date of birth : 1927-04-07

Date of death : 2003-04-06

Birthplace : Ajido, Lagos State, Nigeria

Nationality : Nigerian

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2012-01-05

Credited as : Drummer, Musician, Social activist

0 votes so far

Babatunde Olatunji influenced contemporary jazz's turn to African rhythms back in the 1960s. A respected musician and tireless promoter of African music and culture, he was also a key figure in the rise of world-beat music in the 1980s, and he teamed with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart to record the Grammy Award-winning 1991 release, Planet Drum. Olatunji died of complications from advanced diabetes in April of 2003, just a day before his 76th birthday, and was eulogized in a variety of publications. Sing Out!'s Richard Dorsett termed him "African music's foremost ambassador of the power of rhythm," while New York Times music critic Jon Pareles recalled the drummer's personal philosophy: "Rhythm is the soul of life," Olatunji liked to say. "The whole universe revolves in rhythm. Everything and every human action revolves in rhythm."

Born on April 7, 1927, Olatunji grew up in the fishing village of Ajido, some 40 miles from Nigeria's largest city, Lagos. His father was a fisherman, and the family belonged to the Yoruba tribe, one of the country's largest ethnic groups. Drumming was an integral part of Yoruba ceremonial life, and Olatunji was fascinated by the form from an early age. "I was very inquisitive," he told Guardian journalist Ken Hunt, "and every weekend I would go to village festivals. I was always behind those master drummers, watching them play." He also came of age during an era when the first radio sets appeared in Nigeria, and he was drawn to the sounds of American jazz, gospel, and classical music heard on the British Broadcasting Corporation's (BBC) World Service.

In his teens, Olatunji moved to Lagos to attend a Baptist school, and he read about a Rotary International Foundation scholarship to the United States in a Reader's Digest magazine. Chosen as a 1950 recipient, Olatunji left his homeland for Atlanta, Georgia, where he enrolled at Morehouse College, a historic black school. He planned to study political science, but his interest in music continued to grow. He began to realize that the rhythms he heard in some Western music--particularly those with links to African American slave culture--had echoes of the West African music of his youth. The Desi Arnaz hit "Babalu" was one example: it was a cover of an Afro-Cuban tune, but it possessed Yoruba roots. "I would sing the whole thing, give them the translation and people were amazed," he told the Guardian. "I would say, 'Well this is what has happened to African music.'"

Olatunji was perplexed that the African American students he met at Morehouse knew so little about the cultural riches of his homeland, and he was drawn into the burgeoning movement to bring traditional African music to a new audience in America. He performed in his first concert at the college in 1953 and became a member of the Morehouse jazz band. During his time at the school, he came to know future civil-rights leader Martin Luther King Jr., just two years his senior. After earning his degree in 1954, Olatunji entered graduate school at New York University, with the goal of becoming a career diplomat. Still short on funds, he formed a drum and dance group that performed traditional West African music at multicultural events in the city; King even hired him to perform at civil rights rallies.

Olatunji was still active in campus politics, and he served as president of the African Students Unions of America for a time. In this capacity, he was invited to take part in the 1958 All African People's Conference in Accra, Ghana. The event had been the idea of Ghana's nationalist president, Kwame Nkrumah, and it was Nkrumah who suggested the career turn that shaped Olatunji's life. "I was still pursuing an academic and political career, but Nkrumah told me I should be our cultural ambassador," Olatunji recalled in an interview with George Kanzler, a writer for the Newark, New Jersey-based Star-Ledger. "He said African culture and personality had to be preserved." Nkrumah even arranged for a large shipment of drums to be sent back to New York for Olatunji.

A Radio City Music Hall concert that Olatunji participated in served as another turning point. Columbia Records executive John Hammond, who had worked with Billie Holiday and would later discover both Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen, signed Olatunji to the label, and his first release, Drums of Passion, appeared in 1959. It is considered the first African music ever recorded in a contemporary U.S. studio. Ethnomusicologists had brought back tapes of traditional ceremonial drumming, but Olatunji's debut "reached a mass public with its vivid sound and exotic song titles like 'Primitive Fire,'" noted Pareles in the New York Times.

Drums of Passion was actually released under the name "Michael" Olatunji but was later reissued under his own name. Poorly informed about his options, Olatunji also signed away his royalty rights, and in the end he earned little money from the record. He wrote music for the Broadway production of Lorraine Hansberry's acclaimed play, A Raisin in the Sun, but earned just $300 from that job. In 1961 he performed at inauguration ceremonies for U.S. President John F. Kennedy, and he released his second LP, Zungo! The following year, he was mentioned with other black icons, including King, in Bob Dylan's "I Shall Be Free." He was invited to perform at the African Pavilion of the 1964 New York World's Fair, and with money earned then he established the Olatunji Center for African Culture in Harlem a year later. There, Olatunji supplemented his income by teaching workshops in African music, dance, and language that were frequented by a new generation of jazz musicians in New York. The burgeoning "free jazz" movement incorporated African polyrhythms into its forms, and West African echoes became standard in new music from John Coltrane, Yusef Lateef, and Clark Terry, among others. Coltrane even dedicated a song, "Tunji," to Olatunji, and the last concert the avant-garde saxophonist gave before his death in 1967 was at the Olatunji Center. Rock musician Carlos Santana covered Olatunji's "Jin-Go-Lo-Ba," first heard on Drums of Passion, under the title "Jingo," for his first single in 1969.

Olatunji continued to release records on the Columbia label for a few years in the 1960s, but he still struggled financially. He even thought about moving back to Nigeria at one point. But his influence in the counterculture deepened, heightened by a new interest in traditional drumming as a path to spiritual self-awareness, and he found extra work teaching at the Esalen Institute in Big Sur, California. He also taught at the Omega Institute in Rhinebeck, New York. "Drums are for communication, for socialization and, most importantly, for healing," he explained to Austin American-Statesman journalist Michael Point. In the 1980s he gave more than 2,000 performances across American college campuses and abroad as well. His links to Morehouse helped revive his career in 1986, when fellow alumnus Bill Lee introduced him to his son, a young filmmaker named Spike, who hired Olatunji to score part of his groundbreaking 1986 feature-film debut, She's Gotta Have It.

That same year, the Rykodisc label signed Olatunji, and he began releasing records such as 1988's Drums of Passion: The Invocation. Another link to his past surfaced in the form of Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart, who had been a student at a Long Island school that Olatunji visited in the 1960s as part of his educational-outreach work with the Center for African Culture. Hart was fascinated by Olatunji's traditional drums, and in 1991 the pair teamed to form the ensemble Planet Drum. Bringing Brazilian vocalist Flora Purim and a host of other world musicians on board, they recorded an eponymous debut that won the Grammy Award for World Music in 1991.

Olatunji's last studio release was Love Drum Talk for the Chesky label in 1997. He continued to tour extensively, taking with him a group of dancers, musicians, and singers that performed under the name Drums of Passion. They sang in Yoruba and performed traditional West African dances in distinctive raffia costumes. One of his four children, daughter Modupe, was a member of the troupe, as were some of his seven grandchildren. He declared to the Star-Ledger's Kanzler that he was still an ardent believer in the power of music, and that society was ignoring deeper issues that brought violence and misery to so many lives. "I want to put drums in the hands of young people instead of guns," he told the paper in 1999.

Olatunji was hospitalized because of his diabetes in 2001. He finished work on a new studio album, Healing Session, in 2003, just weeks before he died. The tribute to Olatunji in Sing Out! also mentioned the "rhythm is the soul of life" credo, and Dorsett remarked that "he was right ... long before most of us knew it."

Albums:

-Drums of Passion (1959)

-Zungo! (1961)

-Flaming Drums (1962, Columbia Records CS8666)

-Olatunji

-Soul Makossa (1973, Paramount) (Single/EP)

-Dance to the Beat of My Drum (1986, Bellaphon)

-Drums of Passion: The Invocation (1988, Rykodisc)

-Drums of Passion: The Beat (1989, Rykodisc)

-Drums of Passion: Celebrate Freedom, Justice & Peace (1993, Olatunji Music)

-Drums of Passion and More (1994, Bear Family) Box Set

-Babatunde Olatunji, Healing Rhythms, Songs and Chants (1995, Olatunji Music)

-Love Drum Talk (1997, Chesky)

-Drums of Passion [Expanded] (2002)

-Olatunji Live at Starwood (2003) Recorded Live at the Starwood Festival 1997

-Healing Session (2003, Narada)

-Circle of Drums (2005, Chesky)