Augustus biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Roman Empire

Nationality : Roman

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-12-21

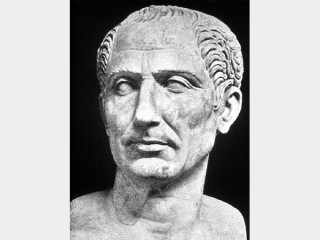

Credited as : First Emperor of Rome, ,

Augustus (63 B.C. - A.D. 14) or Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus was the first emperor of Rome. He established the principate, the form of government under which Rome ruled the empire for 300 years. He had an extraordinary talent for constructive statesmanship and sought to preserve the best traditions of republican Rome.

The century in which Augustus was born was a period of rapid change and, finally, civil war for Rome. Of the many factors which led to the civil wars, two are of crucial importance for understanding his career. By the middle of the 1st century B.C. Rome had conquered nearly all the lands bordering the Mediterranean, and Caesar's conquest of Gaul in 49 B.C. brought transalpine Europe into the sphere of Roman influence.

Rome and its provinces were governed throughout the republic by the Senate, composed largely of members of a small hereditary aristocracy. But the Senate was showing itself unequal to the task of governing the Mediterranean, and its authority was increasingly usurped by the generals in command of the victorious Roman legions. Because he had the support of his army and great personal popularity, Julius Caesar had become virtually a dictator in Rome following his conquest of Gaul. He was strongly opposed by the Senate and in 44 was assassinated by conspirators among them. It was at that juncture that Augustus entered the Roman political arena.

Augustus was born Gaius Octavius on Sept. 23, 63 B.C., in a house on the Palatine hill in Rome. His father, Gaius Octavius, held several political offices and had earned a fine reputation, but he died when Octavius was 4. The people who most influenced Octavius in his early years were his mother, Atia, who was Julius Caesar's niece, and Julius Caesar himself.

When Caesar's will was read, it was revealed that Caesar had adopted Octavius as his son and heir. Octavius was then at Apollonia studying oratory. Against the advice of his friends and family, Octavius—who changed his name to Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus (English, Octavian)— immediately set out for Italy to claim his inheritance. He was only 18, rather frail physically, and although he had delivered the funeral oration for his grandmother when he was 12 and had won Caesar's admiration, he had given no previous indications of his ambitions or his genius for political maneuvering. Octavian displayed both these qualities in abundance as soon as he entered Rome in 43.

Octavian's enemy in his rise to power was Mark Antony, who had assumed the command of Caesar's legions. The two men became enemies immediately when Octavian announced his intentions of taking over his inheritance. Antony had embarked on a war against the Senate to avenge Caesar's murder and to further his own ambitions, and Octavian joined the senatorial side in the battle. Antony was defeated at Mutina in 43, but the Senate refused Octavian the triumph he felt was his due. Octavian abandoned the senators and joined forces with Antony and Lepidus, another of Caesar's officers; they called themselves the Second Triumvirate. In 42 the triumvirate defeated the last republican armies, led by Brutus and Cassius, at Philippi.

The victors then divided the Mediterranean into spheres of influence; Octavian took the West; Antony, the East; and Lepidus, Africa. Lepidus became less consequential as time went on, and a clash between Antony and Octavian for sole control of the empire became increasingly inevitable. Octavian played upon Roman and Western antipathy to the Orient, and after a formidable propaganda campaign against Antony and his consort, Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, Octavian declared war against Cleopatra in 32. Octavian won a decisive naval victory, which left him master of the entire Roman world. The following year Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide, and Octavian annexed Egypt to Rome. In 29 Octavian returned to Rome in triumph.

Octavian's power was based on his control of the army, his financial resources, and his enormous popularity. The system of government he established, however, was designed to veil these facts by making important concessions to republican sentiment. Octavian was extremely farsighted in his political arrangements, but he continually emphasized that his rule was a return to the mos maiorum, the customs of the ancestors. Early in January of 27 B.C., therefore, Octavian went before the Senate and announced that he was restoring the rule of the Roman world to the Senate and the Roman people. The Senate, in gratitude, voted him special powers and on January 16 gave him the title Augustus, signifying his superior position in the state, with the added connotation of "revered." A joint government gradually evolved which in theory was a partnership; in fact, Augustus was the senior partner. Suetonius, his biographer, said that Augustus believed that "he himself would not be free from danger if he should retire" and that "it would be hazardous to trust the state to the control of the populace" so "he continued to keep it in his hands; and it is not easy to say whether his intentions or their results were the better."

The government was formalized in 23, when Augustus received two important republican titles from the Senate— Tribune of the People and Proconsul—which together gave him enormous control over the army, foreign policy, and legislation. His full nomenclature also included his adopted name, Caesar, and the title Imperator, or commander in chief of a victorious army.

Suetonius has given a description of Augustus which is confirmed by the many statues of him. "In person he was unusually handsome and exceedingly graceful at all periods of his life, though he cared nothing for personal adornment… He had clear, bright eyes, in which he liked to have it thought that there was a kind of divine power, and it greatly pleased him, whenever he looked keenly at anyone, if he let his face fall as if before the radiance of the sun. … He was short of stature … but this was concealed by the fine proportion and symmetry of his figure."

Augustus concerned himself with every detail and aspect of the empire. He attended to everything with dignity, firmness, and generosity, hoping, as he said himself, that he would be "called the author of the best possible government." He stabilized the boundaries of the empire, provided for the defense of the frontiers, reorganized and reduced the size of the army, and created two fleets to form a Roman navy. His many permanent innovations included also the creation of a large civil service which attended to the general business of administering so vast an empire.

The Emperor was interested in public buildings and especially temple buildings. In 28 B.C. he undertook the repair of all the temples in Rome, 82 by his own count. He also built many new ones. In addition, he constructed a new forum, the Forum of Augustus, begun in 42 B.C. and completed 40 years later. It was with good reason that Augustus could boast that he had "found Rome built of brick and left it in marble."

Repairing the temples was only one aspect of the religious and moral revival which Augustus fostered. There seems to have been a falling away from the old gods of the state, and Augustus encouraged a return to the religious dedication and morality of the early republic. In 17 B.C. he held the Secular Games, an ancient festival which symbolized the restoration of the older religion. The poet Horace commemorated the occasion with his moving Secular Hymn.

Augustus tried to improve morals by passing laws to regulate marriage and family life and to control promiscuity. In A.D. 9, for example, he made adultery a criminal offense, and he encouraged the birthrate by granting privileges to couples with three or more children. His laws did not discourage his daughter Julia and his grand-daughter (also Julia), both of whom he banished for immoral conduct. Suetonius reports that "he bore the death of his kin with far more resignation than their misconduct."

Throughout his long reign Augustus encouraged literature, and the Augustan Age is called the Golden Age because Roman writing attained a rare perfection. It was above all an age of poets—Horace, Ovid, and most especially, Virgil. And in Virgil's great epic, the Aeneid, there is expressed for all time the sense of the grandeur of Rome's imperial destiny which culminated in the age of Augustus.

Augustus suffered many illnesses, and these caused him to designate an heir early in his reign. But he had many deaths to bear and outlived his preferred choices, including his two young grandsons, and was finally forced to designate as his heir Tiberius, his third wife's son by her first marriage.

The first emperor died at Nola on Aug. 19, A.D. 14. On his deathbed, according to Suetonius, he quoted a line used by actors at the end of their performance: "Since I've played well, with joy your voices raise/ And from your stage dismiss me with your praise."

The main ancient source for Augustus's life is Suetonius's chapter "The Deified Augustus" in the Lives of the Twelve Caesars. The career of Augustus is also discussed in Tacitus's History. Augustus left an account of his own deeds called the Res gestae, or more popularly, the Monumentum ancyranum. John Buchan, Augustus (1937), is still the standard biography in English. Much that is valuable relating to Augustus's career may be found in T. Rice Holmes, The Architect of the Roman Empire (2 vols., 1928-1931), and in Ronald Syme, The Roman Revolution (1939). See also Henry Thompson Rowell, Rome: In the Augustan Age (1962).