Aspasia Of Miletus biography

Date of birth : -

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Miletus, Greece

Nationality : Greek

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-12-21

Credited as : Scholar, invovment with statesman Pericles, daughter of Axiochus

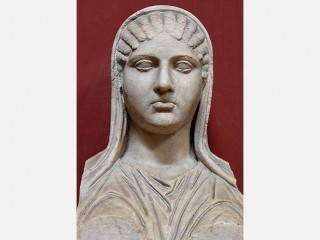

A contributor to learning in Athens, Aspasia of Miletus (c. 470-410 BC) boldly surpassed the limited expectations for women by establishing a renowned girl's school and a popular salon. She lived free of female seclusion and conducted herself like a male intellectual while expounding on current events, philosophy, and rhetoric. Her fans included the philosopher Socrates and his followers, the teacher Plato, the orator Cicero, the historian Xenophon, the writer Athenaeus, and the statesman and general Pericles, her adoring common-law husband.

Renowned for talent, brilliant accomplishments, and beauty, Aspasia, daughter of Axiochus, was born to a literate Anatolian household around 470 BC in Miletus, the southernmost Ionian city and the greatest Greek metropolis of Asia Minor. Although there is no history of her early life, she obtained an education and developed interests in high culture. Her attainments were unusual for a woman living in the male-dominated societies of the eastern Mediterranean.

Aspasia may have left home because she was orphaned about the time she reached marriageable age. As a member of the household of her sister, wife of the Athenian military leader Alcibiades, she emigrated northwest to Greece around 445 BC. For a livelihood, she developed a reputation as a fascinating, vivacious hetaira, one of many refined, educated courtesans or companions to learned male aristocrats. In the spite-tinged words of the comic playwright Aristophanes, she first opened a brothel at Megara. Along with some of her prostitutes, she traveled east to Athens to seek her fortune.

According to the biographer Plutarch's "Life of Pericles," Aspasia studied the flirtations of the courtesan Thargelia of Ionia and openly courted powerful men. Aspasia's "rare political wisdom" attracted the top male, Pericles, the Greek statesman and general who was then governor of Athens. Escaping a faltering marriage of many years, he divorced his wife, who took up with another man, and pursued Aspasia.

The alliance benefited both parties. Pericles established a loving relationship with Aspasia, whom some describe as his second wife. He drew criticism for becoming a homebody and the love slave of the Milesian outsider, whom malicious gossips privately accused of procuring women for the Athenian elite. In truth, Aspasia's brilliance may have had a greater appeal than her charm or sexual skills. As his mistress and intellectual equal, she maintained a stimulating open house that drew scholars, artists, scientists, statesmen, and intellectuals to discussions of current events, literature, and philosophy.

Because Aspasia was a Milesian, she lacked the protections of Athenian citizenship, including the right to marry. However, she turned her unique social position into an advantage. Living outside the traditional obstacles to education and the arts that Greek males imposed on women, she wrote and taught rhetoric at a home school she established for upper-class Athenian girls. She audaciously encouraged female students to seek more education than mere home tutoring in sewing, weaving, dance, and flute playing. The quality of her instruction also attracted interested men and their wives and mistresses. Famous Athenians participating in her salon include Socrates, his disciples Aeschines and Antisthenes, and perhaps the sculptor Pheidias and tragedian Euripides.

Aspasia's excellence at conversation, logic, and eloquent speech influenced Athenian philosophy and oratory. Socrates quoted her advice on establishing a lasting marriage by selecting a truthful matchmaker. Ironically, he held up Aspasia as a model mate. Distinguishing herself from the average Athenian housewife, she was an equal marriage partner to Pericles and the wise steward of their household goods.

Numerous accounts depict Aspasia's behind-the-scenes influence on political affairs. Socrates's dialogue "Menexenus" praises Aspasia for composing speeches for Pericles. One example, the classic funeral oration that he delivered over the casualties of the Peloponnesian War, Plato credits entirely to Aspasia. The comic playwright Aristophanes implied that her influence on the great statesman was so powerful that, in 432 BC, she persuaded him to issue a restrictive Megarian trade accord in retaliation against citizens of Megara who kidnapped girls from her brothel. Historically, his charge remains unsubstantiated.

Although highly regarded by the wise men of Athens and valued by Pericles for her counsel, Aspasia was charged with engineering wars on Samos and Sparta. Greek satirists ridiculed Pericles by calling his mistress unflattering names—Omphale, Dejanira, Juno, and harlot. In the stage comedy Demes, Eupolis openly denigrated Pericles by labelling his domestic companion a common courtesan. In 431 BC, on the eve of the Peloponnesian War, Pericles successfully defended her before 1,500 jurors from the Athenian comic poet Hermippus's unfounded charges that she procured freeborn women for Pericles and that she also maligned Greek gods. Despite these public humiliations, she remained with Pericles for about 16 years, until his political decline and death in 429 BC, during the outbreak of plague that killed a third of the city's population.

According to the historian Thucydides, for political reasons, Pericles sponsored a law in 451 BC that declared as aliens all people born of non-Athenian parentage. The statute not only denied Athenian citizenship to Aspasia, but also to her son, the younger Pericles, the statesman's only surviving son and heir after Xanthippus and Paralus, two sons born to his first marriage, died of plague. Because so many leaders perished during the epidemic, under a special dispensation requested by the elder Pericles, Aspasia's son became a citizen. He distinguished himself during the Peloponnesian War as a general at the battle of Arginusae in 406 BC and afterward was executed along with other captured Athenian war strategists.

Aspasia's last years are largely unchronicled. She took up with Lysicles, a minor leader and sheep dealer who fathered her second son. Until Lysicles's death in 428 BC, he profited politically from associating with Pericles's former common-law wife. Although many references to her appear in ancient writings, her words survive only through quotations from contemporaries. In the first century BC, the Roman orator Cicero adapted her lesson in inductive logic into a chapter on debate. In 1836, the English poet Walter Savage Landor wrote a series of imaginary letters that pass between Pericles and Aspasia.

Biographical Dictionary of Ancient Greek and Roman Women, edited by Marjorie Lightman and Benjamin Lightman, Facts on File, 2000.

Durant, Will, The Life of Greece, Simon and Schuster, 1939.

Henry, Madeleine M., Prisoner of History: Aspasia of Miletus and Her Biographical Tradition, Oxford University Press, 1995.

Lefkowitz, Mary R., and Maureen B. Fant, Women's Life in Greece and Rome, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Miles, Christopher, and John Julius Norwich, Love in the Ancient World, St. Martin's Press, 1997.