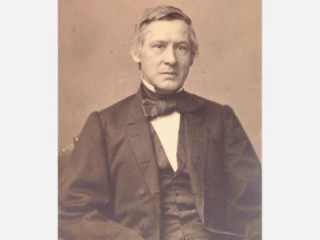

Asa Gray biography

Date of birth : 1810-11-18

Date of death : 1888-01-30

Birthplace : Sauquoit, N.Y.

Nationality : American

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-12-27

Credited as : Botanist, pioneer in the study of plant geography,

Asa Gray, American botanist, pioneered in the study of plant geography and made early attempts to reconcile Darwinian concepts of evolution with traditional religious beliefs.

During the 19th century botany in America emerged as a highly professional vocation involving collaboration among collectors and herbarium specialists. A new method of classification was coming into use early in Asa Gray's career—the so-called natural system, which aimed at classification on the basis of general similarities instead of by the old, Linnaean method of counting the male and female parts of a flower. The new system forced botanists to look more closely at the forms and structures of plants. They began to study the interrelations between plants and their environment and to inquire into their meaning. Gray's professional lifetime bridged these important developments, and he played a part in all of them.

Asa Gray was born at Sauquoit, N.Y., on Nov. 18, 1810. After attending medical courses he received his degree in 1831 and began practice as a country physician. But he had already developed an interest in botany and began to drift away from medicine. From 1832 to 1835 he taught science at a high school in Utica, N.Y., utilizing the summers to improve his botanical knowledge. In 1835 he moved to New York City to begin collaborating with John Torrey on Flora of North America (2 vols., 1838-1843), which firmly established the new natural system of classification in American botany. Publication of the first volume made Torrey and Gray the leading botanists of North America and brought them international attention.

After accepting the professorship of botany at the newly founded University of Michigan, Gray sailed for Europe in 1838 to purchase books for the university and to study the type specimens of American plants in various herbaria. The year-long trip not only prepared Gray for his later task of coordinating North American botany but also laid the foundation of his lifelong friendship with leading European botanists. However, because the opening of the university was delayed, Gray never assumed the professorship.

In 1842 Gray became professor of natural history at Harvard, a post he held until retiring in 1873. The first edition of his Botanical Text-Book (1843) was long a standard work that did much to unify the interpretation and application of technical terms in America. Gray never lost his early interest in popular instruction; he produced five other textbooks, all important in lower-school education.

While at Harvard, Gray became the unofficial but widely recognized coordinator of American botany, maintaining regular correspondence with prominent European botanists and receiving a constant supply of specimens from U.S. government exploring expeditions and correspondents in the West. He created the Harvard department of botany and made its herbarium and botanical garden the finest in America.

Gray was a pioneer in the field of plant geography. In 1859 he published his most famous contribution to this field, a monograph on the botany of Japan and its relations to that of North America. He demonstrated that the similar flora in the two regions had originated in one center and had been dispersed as conditions permitted. (This material was used by Charles Darwin to support his theory of evolution.) To explain the migration of flora in this case, Gray suggested that past geological changes would have made it possible; he thus joined a dynamic theory of the earth with a theory of plant distribution. Relying greatly upon information supplied by James Dwight Dana, a Yale geologist, Gray showed that, on at least two occasions in the past, conditions existed that could have allowed continuity between the flora of the two regions.

On Sept. 5, 1857, Darwin wrote Gray the famous letter in which he first outlined his theory of the evolution of species by natural selection. Gray became Darwin's first American advocate and also one of his most searching critics. Although Gray accepted the main outlines of Darwin's theory, his insistence that evolution must be directed by some external force allowed him to preserve his own Presbyterian beliefs. After Gray's initial review of Darwin's Origin of Species in the American Journal of Science, of which he was a coeditor, Gray spent much of his life arguing on both a popular and a scientific level for the compatibility of evolutionary theory and religion. He also arranged for the first American edition of Origin of Species.

One of the original members of the National Academy of Sciences, Gray was president of both the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science and was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution. He died at home in Cambridge, Mass., on Jan. 30, 1888. His wife, Jane Loring Gray, whom he had married in 1848, edited his autobiography and letters.

Gray's correspondence was edited by Jane Loring Gray, Letters of Asa Gray (2 vols., 1893). An excellent biography which includes an analysis of Gray's contributions to botany is A. Hunter Dupree, Asa Gray, 1810-1888 (1959). See also Andrew D. Rodgers, American Botany, 1873-1892: Decades of Transition (1914; repr. 1944), and Edward Lurie, Louis Agassiz: A Life in Science (1960). For the general scientific background see George H. Daniels, American Science in the Age of Jackson (1968).

Dupree, A. Hunter, Asa Gray, American botanist, friend of Darwin, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1988.