Arthur Fiedler biography

Date of birth : 1894-12-17

Date of death : 1979-07-10

Birthplace : Boston, Massachusetts, United States

Nationality : Australian

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-12-14

Credited as : conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra, ,

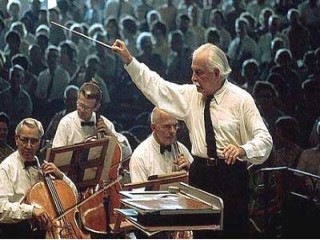

Arthur Fiedler delighted audiences of all ages as conductor of the Boston Pops for fifty years, bringing a mixture of classical music and pop tunes to mass audiences around the world.

Arthur Fiedler garnered many distinctions during his fifty consecutive seasons as conductor of the Boston Pops. He helped bring classical music to mass audiences; conversely, he also gave lighter genres such as pop a respectability they would not have had if he had not performed and recorded their works with his orchestra. Fiedler's albums with the Pops have sold over fifty million copies, and his rendition of Danish composer Jacob Gade's "Jalousie" became the first record by a symphony orchestra to sell over a million copies. In addition to being the toast of the city of Boston while he led the Pops, Fiedler and his orchestra toured extensively throughout the United States and the rest of the world. For his musical efforts, the conductor received many tributes, including the United States' highest civilian award, the Medal of Freedom, and France's Legion of Honor. When Fiedler died in 1979, he was eulogized in Newsweek by Hubert Saal as "neither elitist nor specialist" and "renowned" for his "resoundingly middlebrow musical taste that embraced high and low with equal respect and zest."

Fiedler was born in Boston on December 17, 1894, to a musical family. His father played violin for the Boston Symphony, and his mother played the piano, though not professionally. So many of his father's ancestors had been violinists in Austria that over the years their surname became Fiedler, the German word for "fiddler." Not surprisingly, Arthur Fiedler's father determined that his son should continue in the family tradition, and provided him with violin lessons in his childhood. Fiedler, however, told Stephen Rubin in the New York Times that he did not particularly enjoy either those or the piano lessons he also received. "It was just a chore, something I had to do, like brushing my teeth," he explained. When his family moved to Berlin, Germany in 1910, Fiedler briefly rebelled against his father's plans for him and became an apprentice at a publishing firm there. He quickly tired of the business, however, and returned to his musical efforts.

While his family was in Europe, Fiedler was fortunate enough to be accepted at Berlin's Royal Academy of Music. Though he concentrated on studying the violin, he also took classes in conducting, which, even then, he liked better. Fiedler used his violin to support himself, however, by playing in small orchestras and in cafes. He continued in this type of musical job when his family returned to the United States to avoid the dangers of World War I. By 1915 he had won a spot as a second violinist in the Boston Symphony Orchestra, hired by then-conductor Karl Muck.

After a brief period in the U.S. Army—from which he was discharged for having flat feet—Fiedler returned to the Boston Symphony in 1918. For some time he played the viola for the orchestra, and also served as a substitute on many other instruments, including the piano, organ, celesta, and, of course, the violin. He longed to conduct, however, and though he remained with the Boston Symphony, he began conducting smaller musical groups such as the MacDowell Club Orchestra and the Cecilia Society Chorus. With some of his fellow Boston Symphony musicians, Fiedler formed the Boston Sinfonietta, a small chamber orchestra that specialized in performing unusual and little-heard classical compositions. As Richard Freed reported in Stereo Review, the Sinfonietta was "perhaps the only permanently constituted chamber orchestra in the country in the 1930s." Freed went on to laud its achievements: "The Sinfonietta made the premiere recording of Hindemith's viola concerto Der Schwanendreher, with the composer as soloist. With organist E. Power Biggs there were works of Handel, Corelli, and Mozart. There were the big Mozart Divertimento in B-flat Major, K. 287, and the Wind Serenade in C Minor, K. 388, Telemann's Don Quichotte suite, and such rarities as the marvelous little Christmas Symphony of Gaetano Maria Schiassi and a suite by Esajas Reusner (the latter with the first U.S. recording of the Pachelbel Canon as filler)."

Not content with his many musical activities, Fiedler in 1927 began an effort to gain support for free outdoor concerts. He later told Newsweek: "I believed people should have an opportunity to enjoy fine music without always having to dip into their pockets." By 1929 Fiedler had his way, and he conducted selected members of the Boston Symphony in the first of what became known as the Esplanade Concerts, on the banks of Boston's Charles River.

The following year, Fiedler became permanent conductor of the Boston Pops, an orchestra drawn from the Boston Symphony for the purpose of performing lighter classical music. At its helm, Fiedler led the group to heights of popularity that had hitherto escaped it. By the end of his first season as the Pops' conductor, he had achieved great personal fame in and around the Boston area. He began recording with the Pops in 1935, and their popularity began to spread to the rest of the United States—and to the rest of the world.

Throughout his lengthy tenure with the Pops, Fiedler was not afraid of innovation. In addition to serving up renditions of lighter classics such as Strauss waltzes, he would often add to his programs versions of Broadway tunes or popular hits of the day. With the Pops, Fiedler made recordings of the songs of George and Ira Gershwin, and was one of the first "serious" musicians to recognize the worth of the Beatles' efforts, successfully featuring some of their songs—including "She Loves You"—in Pops concerts. Shortly before his death from cardiac arrest on July 10, 1979, Fiedler and the Pops made an album of songs from the disco-celebrating film Saturday Night Fever, aptly titled Saturday Night Fiedler. Saal quoted Fiedler about his approach to music selection: "I think the snobs are missing something. There's no boundary line in music, I agree with Rossini: 'All music is good except the boring kind."' Similarly, a Time reporter recorded more of the conductor's words: "My aim has been to give audiences a good time. I'd have trained seals if people wanted them."

Though towards the end of his time as leader of the Boston Pops Fiedler's health was poor and he needed the help of assistant conductor Harry Ellis Dickson, he remained active with the group practically up to his death. As Time reported: "Toward the end, the proud old man would shuffle unsteadily to the podium. But then, invigorated by the music, he seemed to shed 20 years."