Artemisia Gentileschi biography

Date of birth : 1593-07-08

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Rome, Italy

Nationality : Italian

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2010-07-28

Credited as : Artist painter, ,

2 votes so far

When Ingrid D. Rowland noted in the New Republic, "Artemisia Gentileschi has arrived," the reviewer was referring to the appearance of works by the formerly obscure Italian Baroque painter in a significant traveling exhibit as well as in several scholarly studies, novels, and a French film. Mary O'Neill, writing in the Smithsonian, credited such belated recognition to the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art's exhibition of Gentileschi's paintings alongside those of the artist's father, Orazio Gentileschi, for establishing her as "one of the very few female painters of her time bold enough to tackle historical and allegorical themes." Part of Gentileschi's appeal is her life story; As O'Neill wrote, "Tarnished by scandal and hindered by a society that expected women to be either nuns or wives, ... Gentileschi nevertheless became the most accomplished female painter of her time."

The scandal O'Neill was referring to was her repeated rape by her art teacher, Agostino Tassi, and the subsequent trial which found Tassi guilty. This unfortunate incident has added to the painter's cachet with modern audiences. As Ann Sutherland Harris noted in GroveArt.com, while Gentileschi has been "celebrated by 20th-century feminists and by women artists," such personal notoriety is only part of the draw; Gentileschi also paved a new path for female painters. "From the beginning," Sutherland commented, "she refused to limit herself to portraits, still-lifes and small devotional pictures, the staples of most women artists in the 16th and 17th centuries, but established herself immediately as an ambitious history painter." Exposed to the work of Caravaggio in Rome, she spread that painter's revolutionary use of light and surface detail to other parts of Italy and abroad. According to Arthur C. Danto, writing in the Nation, Gentileschi "belongs to [the] great company [of Rembrandt, Ludovico Caracci, Lucas Cranach, Veronese, and Tintoretto] by virtue of her artistic achievements, but it was her gender that defined her artistic identity." "Gentileschi is worthy of note for two reasons," James Gardner wrote in the National Review. "The first is the fact that she was an indisputably good painter, better than almost anyone alive today. The second is that when someone gets round to writing the intellectual history of the last quarter of the twentieth century, she will play no small role."

An Inspiring Life

Gentileschi's life was comprised of her many difficult roles: as a woman fighting the male biases and domination of her day; as the daughter of a cold and rather distant father; as a survivor of rape; as one partner in an unhappy marriage of convenience; and as a victim of eventual poverty and poor health. However, Gentileschi cannot be regarded as a victim; she was a self-assured painter who created shocking images, a woman reputed to know her own mind about men and lovers. Also, as Gardner noted, there is the theme of the "thoroughly independent woman who, in a colorful and picaresque life, traveling unescorted through Italy and England, triumphantly overcame the prejudices and intrigues of jealous male rivals to win the esteem of kings and councilors."

In fact, Gentileschi's personal story has at times overshadowed the work itself: only thirty-four canvasses have survived out of a much larger number of completed works, but these attest to her skill with light and surface texture, as well as to her daring, challenging themes, especially in several disturbingly violent works. Judith Slaying Holofernes, for example, finds the Hebrew Judith, aided by her servant, cutting off the head of the Assyrian captain "in a spray of blood, tangled bedclothes, and stifled screams," as Rowland described the scene. Rowland found that such paintings by Gentileschi "throb with passion," and added that the painter's work, "like her life, was seldom for the faint at heart." A critic writing in the International Dictionary of Art and Artists also addressed this issue of Gentileschi's art versus her life: "It is tempting to adduce the established biographical data in partial explanation of the contexture of her art: the sympathy and vigor with which she evokes her heroines and their predicaments, and her obsession with that paradigmatic tale of female triumph, Judith and Holofernes. But such possibilities should not distract attention from the high professional standards which Artemisia brought to her art."

Roman Beginnings

Gentileschi was born in 1593 in Rome, the first child of well-known painter Orazio Gentileschi, who raised his daughter after the death of the mother. Orazio was a disciple of the artist Michelangelo de Merisi da Caravaggio and his emphasis on surface effects including the use of contrasting light and dark spaces in a canvas, or chiaroscuro. The older Caravaggio, who died in 1610, was also noted for his surprising realism, eschewing classical concepts and the idealized themes of such paintings, and used dramatic moments to create tension in his paintings. Orazio taught his daughter such techniques, and soon she proved to be a better painter than her brothers. Such artistic training for female members of artistic families was not uncommon in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries in Italy, where other women, such as Sofonisba Anguissola, Lavinia Fontana, and Elisbetta Sirani all came to prominence. However, the work of Gentileschi quickly outpaced that of these other women.

Gentileschi's first major work, Susanna and the Elders, was completed when she was just seventeen, and though it is assumed that she received some help from her father in its composition, the painting demonstrates her facility with surface details and creating dramatic moments. For Harris, writing in GroveArt.com, this early painting, depicting church elders attempting to seduce a young virgin, "is extraordinarily accomplished and addresses the themes that she favoured throughout her career--women heroines and the female nude." Even such early work, according to the International Dictionary of Art and Artists critic, shows "a greater freedom of brushwork than that of her father," as well as a "certain authenticity of emotion."

Despite her obvious talent, Gentileschi was barred from entrance to academies of art of the time because of her gender. In 1611, Orazio arranged for perspective lessons from a fellow artist, Tuscan painter Agostino Tassi, who betrayed the family trust by bribing servants and gaining entrance to the young woman's room one night and raping her. Afterward, he promised marriage, and gained further access to her room and body. When it was discovered that Tassi was already married and had no intention of marrying his student, Gentileschi's father brought suit against Tassi. The resulting seven-month trial provided Rome with fuel for gossip, with Tassi claiming that Gentileschi was no virgin when they first had sex, and that she had a reputation for sexual exploits. Gentileschi was forced to undergo a physical examination and a trial by pain to ascertain if she were telling the truth. The judge in the proceedings found against Tassi, who was also charged with attempting to have his wife murdered. However, the painter served less than a year in prison, and eventually worked again with Orazio Gentileschi. A month after the trial, a marriage was arranged between Gentileschi and Florentine artist Pietro Antonio di Vicenzo Stiattesi, and the couple later moved to Florence.

The Florentine and Roman Period

Even while on trial, Gentileschi was at work, and she now took up the theme of the Jewish heroine Judith, a woman who helped save her people from attack by killing the enemy general, Holofernes. Judith Slaying Holofernes has been seen by many critics as the artist's attempt to work out emotions regarding her rape and the subsequent humiliation of the trial. As Harris put it, Artemisia "emphasizes the brutal facts of decapitation to such a degree that most people find it hard to look at the picture." Still, Harris noted, "the painting has a mesmerizing power and is full of beautifully painted details." Such early paintings display, according to the International Dictionary of Art and Artists essayist, a "vigorous sense of drama," and "are emotional without being sentimental."

While living in Florence with her husband, Gentileschi learned to read and write; she also came into her own as an artist in addition to bearing several children, only one of whom, a daughter named Prudentia, survived. During her years in Florence, the artist received commissions from the grand-nephew of famous Italian painter Michelangelo, including her Allegory of Inclination, and from the powerful duke of Florence, Cosimo de Medici, including The Penitent Magdalene. In 1616, Gentileschi was honored with membership in Florence's all-male art academy, the Accademia del Disegno, an indication of the respect her peers paid her. Meanwhile, all was not well at home; along with the death of three of her children, Gentileschi had to deal with her husband's infidelity and extravagant spending.

Eventually bankrupt, Gentileschi and her family fled creditors and returned to Rome in 1621, where she eked out a living as a painter and produced some of her most important works. Her well-known Judith and Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes features a night scene lit by candlelight that was a new effect for Artemisia, experimenting with light coming from an internal, rather than external source. As the International Dictionary of Art and Artists critic noted, "Painterly and sensuous handling, flow of action, theatrical deployment of light and gesture, and judicious selection of dramatic moment combine to effect a riveting illusion."

While her artistic reputation continued to grow, domestic matters continued to plague Gentileschi, however. Her husband finally abandoned the family in 1622, and some reports indicate that the painter gave birth to another child after the end of her marriage. By 1627, she had recognized that aesthetic trends had changed in Florence, and a move to a new area was required in order to gain commissions.

To Venice and Naples

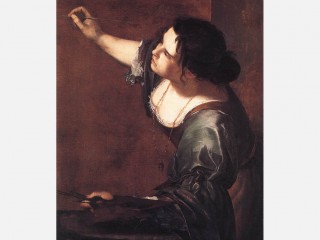

Moving to Venice, Gentileschi remained there for several years before moving to Naples in 1630. She remained in that city--taking a short break working with her father in England in 1638 to 1640--until her death in 1652. Setting up a studio in Naples, she worked on paintings in a cathedral and on religious subjects, such as the Annunciation. She also painted her final self-portrait, Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting.

Little is known of Gentileschi's later life. For a time she worked with her father in England, accepting several commissions, including one from King Charles I to decorate the ceiling of the queen's house in Greenwich. According to scholars, her later career did not produce works that ranked with those produced circa the 1620s. After Orazio Gentileschi's death in 1639, Artemisia remained at the court of Charles I for a time, then returned to Naples in the early 1640s, producing works such as Galatea, Bathsheba, and Diana at Her Bath. She also reworked several earlier canvases, including Susanna and the Elders.

A Creative Legacy

After Gentileschi's death in 1652, the only known contemporary accounts of her passing to be produced were a pair of satiric epitaphs which said not a word about her artistic accomplishments, but instead referred to her only as a sexual libertine. This was the fate of many independent-minded women of Gentileschi's day. Even in her own age, however, she had been a popular and successful artist, considered "one of the most successful painters of her day," according to ARTnews Online contributor Ann Landi. As a measure of Gentileschi's success, the list of her patrons included Cosimo de Medici, Philip IV of Spain, several members of the papal family, and the king of England. She was able to employ her brothers as agents, and when her daughter, also a painter, married, Gentileschi was able to supply a hefty dowry.

In her own time, Gentileschi helped spread the realism and the use of light pioneered by Caravaggio, and she became a major influence on painters of subsequent generations. However, it was only after several centuries that she would finally come into her own; in the late twentieth century both her art and her biography began to resonate with a more self-conscious culture. While the rise of feminist studies helped rehabilitate Gentlieschi, in the end it was the artwork itself, powerful, dramatic, and accomplished, that made her a leading figure of the Italian late Baroque. As Landi concluded of Gentileschi: "In the end, it is of course the marvelous works that still ravish our eyes and imagination, not the fact the she was a woman or the sensational aspects of her biography."

PERSONAL INFORMATION

Surname pronounced "jahntee-LES-kee"; born July 8, 1593, in Rome, Italy; died 1652, in Naples, Italy; daughter of Orazio (a painter) and Prudentia (Montoni) Gentileschi; married Pietro Antonio di Vicenzo Stiattesi (a painter), 1612, (marriage ended, c. 1622); children: three sons, Prudentia (daughter).

AWARDS

Elected first female member of Accademia del Disegno (artists' guild; Florence, Italy), 1616.

CAREER

Painter. Major works include Madonna and Child, c. 1609; Susanna and the Elders, 1610; Judith Slaying Holofernes; The Penitent Magdalene, c. 1617-20; Lucretia, c. 1621; A Condittiere, 1622; Judith and Her Maidservant with the Head of Holofernes, c. 1625; Self-Portrait as an Allegory of Painting; Annunciation, 1630; Birth of St. John the Baptist, 1631-33; Finding of Moses, c. 1633; Adoration of the Magi, 1636-37; Bathsheba, c. 1646-49. Exhibitions: Work included in "Orazio and Artemisia Gentileschi: Father and Daughter Painters in Baroque Italy," Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY, 2002. Works included in permanent collections at Pitti Palace, Florence, Italy; Schloss Weissenstein, Pommersfeld, Germany; Palazzo Cattaneo-Adorno, Genoa, Italy; Uffizi Gallery, Florence; Casa Buonarroti, Florence; Galleria Nazionale, Rome; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Moravian Gallery, Brno, Czech Republic; and Detroit Institute of Arts, MI, among others.