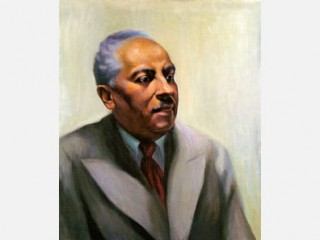

Arna Bontemps biography

Date of birth : 1902-10-13

Date of death : 1973-06-04

Birthplace : Alexandria, Louisiana

Nationality : American

Category : Arts and Entertainment

Last modified : 2022-02-15

Credited as : Librarian and poet, critic and novelist, Arna Bontemps quotes and poems

Arna Bontemps was an accomplished librarian, historian, editor, poet, critic, and novelist. His diverse occupations were unified by the common goal of forwarding a social and intellectual atmosphere in which African-American history, culture, and sense of self could flourish.

Bontemps was born on October 13, 1902 in Alexandria, Louisiana, to Creole parents, Marie Carolina Pembrooke and Paul Bismark Bontemps. His relationship with his father, a stonemason turned lay minister in the Seventh Day Adventist church, was complicated by his attachment to his mother, a former schoolteacher, who died when Bontemps was twelve. She had instilled in her son a love for the world of books and imagination stretching beyond his father's view that life consisted of practical concerns.

Several racially motivated incidents led the strong-willed Paul Bontemps to relocate his family to Los Angeles when Arna was three. He and the more exuberant Uncle Buddy, younger brother of the grandmother with whom Arna went to live in the California countryside, proved to be contradictory influences upon Arna after his mother's death. As the older of two children, Arna disappointed his father by choosing a life of writing over following four generations of Bontemps into the stonemason's trade. It was the warm, humorous Uncle Buddy who became for his great-nephew a resource for, as well as support of, the art of storytelling. While Paul Bontemps respected Uncle Buddy's ability to spell and read, he disapproved of his alcoholism, his association with the lower classes, and his fondness for minstrel shows, black dialect, preacher and ghost stories, signs, charms, and mumbo jumbo. Through Buddy, however, Arna Bontemps was able to embrace the black folk culture that would form the basis for much of his writing.

To counter what he perceived as the pernicious effects of Uncle Buddy's attitudes, the elder Bontemps sent his son to San Fernando Academy, a predominantly white boarding school, from 1917 to 1920, with the admonition, "Now don't go up there acting colored." As Arna grew older, he found his parents' antipathy to their own blackness echoed by educators and intellectuals sympathetic to the philosophy of assimilationism. He later pronounced such views efforts to "miseducate" him. He began to understand the opposing responses of his great-uncle and his father toward their racial roots as symbolizing the conflict facing American blacks to "embrac[e] the riches of the folk heritage" or to make a clean break with the past and all that it signified. He concluded that American education reduced the Negro experience to "two short paragraphs: a statement about jungle people in Africa and an equally brief account of the slavery issue in American history." He would devote his life to reinstating the omissions.

Bontemps's diverse occupations were unified by the common goal of forwarding a social and intellectual atmosphere in which African-American history, culture, and sense of self could flourish. Having graduated from Pacific Union College in 1923, he moved from California to New York City to teach at the Harlem Academy and to write. Bontemps became fast friends with Langston Hughes, a physical lookalike as well as an intellectual twin, evidenced by Hughes's 1926 manifesto on black art which became Bontemps's as well: "We younger Negro artists who create now intend to express our individual dark skinned selves without fear or shame."

In the summer of 1924, at age twenty-one, Bontemps published a poem, "Hope," in Crisis, a journal instrumental in advancing the careers of most of the young writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance. Recognition thereafter came quickly with his poems "Golgotha Is a Mountain" and "The Return," which in 1926 and 1927, respectively, won the Alexander Pushkin Award for Poetry offered by Opportunity: Journal of Negro Life, and "Nocturne at Bethesda," which in 1927 won a first prize for poetry from Crisis. Both the Opportunity pieces are atavistic poems connecting Bontemps to other Harlem Renaissance poets who express a longing for their roots in Africa. They synthesize racial consciousness and personal emotion, rendering the theme of alienation central to so much of Renaissance poetry. They also suggest through images of jungles, rain, and the throbbing of drums the attempt to return to original sources, to unleash racial memory by moving back to a more primitive, more sensuous time. Bontemps asserts the archetypal black consciousness as a suffering but indomitable self, a symbol of endurance. In "Nocturne for Bethesda," as in many other poems, he juxtaposes racial consciousness with the traditional Christianity of his youth, lamenting in this poem the inability of religious teachings to make the suffering of the black race meaningful; only through the power of racial memory can blacks find solace. But while the poet recognizes the sustenance gained from such a return in consciousness, he also acknowledges that only a moment of intense insight is possible before the vision fades in the harsh light of reality. Although his stay in Harlem spanned barely seven years, Bontemps interacted with a chorus of new voices who made the Harlem Renaissance a golden age of black art. In addition to Hughes, these included Jean Toomer, Claude McKay, James Weldon Johnson, Countee Cullen, and Zora Neale Hurston.

Although Bontemps harbored plans of pursuing a Ph.D. in English, the Great Depression, family responsibilities, and the demands of his writing contracts with publishing houses stifled such hopes as well as the spirit of optimism that pervaded his early verse. Having married Alberta Johnson on August 26, 1926, Bontemps was now a family man

already supporting two of the six children he would eventually father. Forced by economic necessity to leave the Harlem Academy in 1931, Bontemps taught at Oakwood Junior College, a black Seventh Day Adventist school in Huntsville, Alabama. His situation there mirrored the working conditions of much of his career: he was typically short on funds and rarely had a comfortable place to work. His persistence paid off, however, particularly when he turned to writing children's books in the belief that a younger audience was more receptive to the positive images of blacks he wished to instill. Over the next forty years he wrote and edited such books for children and adolescents as Popo and Fifina (1932), You Can't Pet a Possum (1934), We Have Tomorrow (1945), Frederick Douglass: Slave-Fighter-Freeman (1959) and its sequel Free at Last: The Life of Frederick Douglass (1971), and Young Booker: Booker T. Washington's Early Days (1972).

His first novel, God Sends Sunday, the story of the most successful black jockey in St. Louis, was published in 1931. Most critics were receptive to the book, and Bontemps himself liked the story well enough to collaborate with Countee Cullen to turn it into a play, St. Louis Woman (1939). It premiered in New York on March 30, 1946, and ran for 113 performances. Bontemps's efforts to alter the perception of blacks in American literature ultimately proved disadvantageous to his teaching career: the administration of Oakwood Junior College accused him of promoting subversive racial propaganda and allegedly ordered him to burn his books. He resigned in 1934 and took his family to California, much as his father had done years before.

While "temporarily and uncomfortably quartered" with his father and stepmother, Bontemps produced Black Thunder, his best and most popular novel. Published in 1936, it offers a fictional version of an 1800 slave rebellion led by Gabriel Prosser. Rendering the theme of revolution through the device of the slave narrative, the novel has become one of the great historical novels in the American tradition.

In 1935 Bontemps accepted a teaching assignment at the Shiloh Academy in Chicago, resigning in 1937 to work for the Illinois Writer's Project. The Caribbean flavor of some of his writing may be traced to a study tour in the Caribbean subsidized by a Rosenwald Fellowship for creative writing received in 1938 and renewed in 1942. His third novel, Drums at Dusk, appeared in 1939; continuing his interest in slave history, it depicts the revolt of blacks in Haiti occurring simultaneously with the French Revolution.

After receiving a master's degree in library science from the University of Chicago in 1943, Bontemps was appointed head librarian at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee, where he remained until 1965. During this period he received two Guggenheim Fellowships for creative writing (1949, 1954). Using his friendship with Hughes to establish at Fisk University Library a Langston Hughes collection, securing as well the papers of such Harlem Renaissance figures as Jean Toomer, James Weldon Johnson, and Countee Cullen, and establishing a collection to honor George Gershwin, Bontemps made the library an important resource for the study of African-American culture.

While his poetry, fiction, and histories have been widely recognized, perhaps Bontemps's most enduring contribution to African-American literary history lies in the scholarly anthologies he compiled and edited, alone or in collaboration with Hughes. They appeal primarily to high school and college undergraduate students. Golden Slippers (1941) is a collection of poems by black writers suitable for young readers. The Book of Negro Folklore (1958) is a collection of animal tales and rhymes, slave narratives, ghost stories, sermons, and folk songs as well as essays on folklore by Sterling Brown and Zora Neale Hurston. Hold Fast to Dreams: Poems Old and New (1969) is an anthology of poems blending, without chronological or biographical data, works by blacks and whites, English and American authors. Great Slave Narratives (1969); and The Harlem Renaissance Remembered (1972) are collections of eyewitness descriptions of the period accompanied by a memoir by Bontemps.

Bontemps's series of anthologies was capped with a collection of his own poetry in 1963. Personals, consisting of twenty-three poems of the 1920s, remains a moving record of a young black artist exercising his imagination for the first time amid Harlem's turbulent literary and social excitement; it also contains an introductory comment describing the goals of the writers of the period and Bontemps's 1940s reaction to the Harlem milieu of the 1920s. Appropriately titled, the collection reveals the personal wonder of a young man whose consciousness is expanding with the enormous possibilities of self-definition and self-acceptance through art while simultaneously acknowledging a brooding sense of homelessness. This expression of the black self makes Personals a mirror for the development of black American literature during the 1920s. Bontemps captured the significance of the poetry of the period to all black artists in his 1963 introduction to American Negro Poetry: "In the Harlem Renaissance of the twenties poetry led the way for the other arts. It touched off the awakening that brought novelists, painters, sculptors, dancers, dramatists, and scholars of many kinds to the notice of a nation that had nearly forgotten about the gifts of its Negro people."

In 1966 Bontemps renewed his ties with Chicago by teaching black studies at the University of Illinois at Chicago Circle. In 1969 he became curator of the James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection at Yale University, an important repository of original materials from the Harlem Renaissance. By 1971 he was back at Fisk as writer in residence, working on an autobiography he would not live to complete. He died in Nashville of a heart attack on June 4, 1973.

Though his accomplishments as librarian, historian, editor, poet, critic, and novelist were stunning, Arna Bontemps was perhaps as overshadowed by Langston Hughes as Zora Neale Hurston was by Richard Wright. Epitomizing the quiet, understated endurance celebrated in his poems. Contributing in ways large and small to the perpetuation of what was a limited interest in African-American life and culture, Bontemps paved the way for subsequent scholars and writers to find easier access to research materials as well as public recognition. He takes his place as a pioneer who, as Arthur P. Davis asserts, "kept flowing that trickle of interest in Negro American literature—that trickle which is now a torrent."