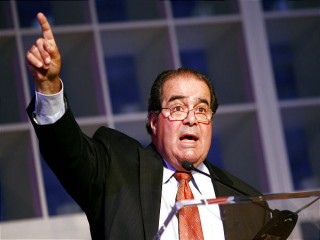

Antonin Scalia biography

Date of birth : 1936-03-11

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Trenton, New Jersey, United States

Nationality : American

Category : Politics

Last modified : 2010-12-17

Credited as : Jurist, Supreme Court member,

Antonin Scalia, a conservative jurist who advocated judicial restraint, was appointed to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan in 1986.

American political conservatives expected to find a friend on the Supreme Court after Antonin Scalia's appointment in 1986. Instead, they found a man dedicated to enforcement of the law and to a fair and equal justice system.

Antonin Scalia was born on March 11, 1936, in Trenton, New Jersey. His father was an Italian immigrant who taught Romance Languages at New York's Brooklyn College and his mother was a schoolteacher. After receiving his undergraduate degree summa cum laude from Georgetown University in 1957 Scalia went on to attend Harvard Law School. There he served as an editor on the prestigious Harvard Law Review. Upon graduation from law school, Scalia stayed on at Harvard as a post-graduate fellow from 1960-1961. In 1960 he married Maureen McCarthy. They would have nine children.

His education completed, Scalia joined the private law firm of Jones, Day, Cockley and Reavis of Cleveland, Ohio and remained there for six years. During this time, Scalia decided he was best suited to teaching the art of law more than practicing it. In 1967 he joined the faculty of the University of Virginia Law School.

In 1971 Scalia left the scholar's life to serve in a variety of government posts: general counsel, Office of Telecommunications Policy, Executive Office of the President (1971 to 1972); chairman, Administrative Conference of the United States (1972 to 1974); and assistant attorney general, Office of Legal Counsel, U.S. Department of Justice (1974 to 1977). Scalia returned to teaching in 1977 as professor of law at the University of Chicago, leaving for a year to serve as a visiting professor at Stanford University (1980-1981).

During the brief period between government service and his return to the university Scalia served as scholar-in-residence at the American Enterprise Institute, a leading center of conservative thought located in Washington, D.C. His association with the institute would prove to be fruitful for Scalia, in terms of the intellectual stimulation it provided him at the time and the prominent conservative contacts it afforded. His service as an editor of Regulation, the institute's journal, gave him a forum to develop ideas that would later find voice in law journals and judicial opinions.

Scalia was not among the nation's leading legal scholars, but he regularly published law review articles and established a reputation in his fields of specialty; administrative law and regulated industries. In his essays, he outlined a conservative philosophy that would mark his career on the appellate bench. Scalia was an advocate of judicial restraint. Judges, he believed, should refrain from promoting their political and social convictions through their opinions. He felt judges should not make laws in the same manner as the legislature. Rather, he felt that the proper role of a judge was to interpret the law and leave matters of legislation to the elected representatives of the people.

In 1982 Scalia was appointed to the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C. by then President Ronald Reagan. Scalia quickly established himself as a leading conservative judge on what was generally acknowledged as the nation's most liberal appellate court. Frequently exercising his right to dissent, Scalia remained faithful to his earlier published views of the judicial role. In cases concerning libel law, sexual discrimination under the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Gramm-Rudman budget control measure, Scalia wrote opinions that expressed his judicial philosophy: strict interpretation of the Constitution and legislative statutes and maintenance of the power of traditional institutions and of the majority's right to make law.

These views, often noted in dissenting opinions from the court, revealed a respect for governmental authority as well as an impatience for the enforcement of minority rights.

When Chief Justice Warren Burger announced his retirement in 1986, President Reagan quickly acted to strengthen the conservative voice on the high bench by naming sitting Justice William Rehnquist as Burger's successor and by appointing Scalia to succeed Rehnquist. Confirmed unanimously by the Senate, Scalia became the first Italian-American to sit on the Supreme Court.

Predicting judicial performance on the Supreme Court has always been a tricky and imprecise business. An article in the November 5, 1990 issue of Newsweek noted that "Scalia sticks with his ideological cards. That tenacity, combined with a sharp pen and mind, and the personal ebullience of Willard Scott, also have made him the most provocative justice." Conservatives considered him their "savior," while liberals labeled him "The Terminator."

In 1992, in the case R.A.V. versus City of St. Paul, Scalia voted to strike down a St. Paul, Minnesota hate speech law as a violation of freedom of speech. Writing for the majority Scalia noted that "special hostility towards the particular biases thus singled out… . is precisely what the First Amendment forbids." The decision affirmed that people could not be punished for their opinions, even if they took the form of a hate crime. That same year, he dissented in the case Lee versus Weisman. A 5-4 majority held that it was unconstitutional to recite a non-denominational prayer at a public high school graduation. In attacking the majority, he called the decision "nothing short of ludicrous."(New Republic January 18, 1993).

In 1996 Scalia, labeled as angry "refused to join the rest of the court in holding that the tax-supported, men-only Virginia Military Institute violated women's right to equal protection of the laws." (Time July 8, 1996). The article went on to call Associate Justice Clarence Thomas "his only dependable ally."

Never one to avoid controversy or cave in to the majority, Scalia dissented in the controversial Romer versus Evans case. The court ruled that "a state constitutional amendment denying legal redress for discrimination based on homosexuality violated the equal-protection clause." (Time July 8, 1996). Scalia wrote a "withering" dissent and openly "scoffed at the majority opinion." (Time July 8, 1996).

In 1997 prominent Republicans mentioned Scalia as a possible presidential candidate for the year 2000, noting, "Scalia is second to none, in terms of his potential for restoring the Reagan coalition." (Insight on the News (February 24, 1997). He also wrote a book A Matter of Interpretation: Federal Courts and the Law where he discussed theories of judging and the judicial system.

For information on the Supreme Court and the justices, see Leon Friedman The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (New York:Chelsea House Publishers, 1997); and Steven G. O'Brien American Political Leaders (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, 1991)