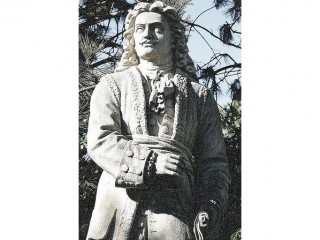

Antoine De Lamothe Cadillac biography

Date of birth : 1658-03-05

Date of death : 1730-10-16

Birthplace : Saint-Nicolas-de-la-Grave, France

Nationality : French

Category : Famous Figures

Last modified : 2010-12-10

Credited as : Explorer and adventurer, founded the Allegheny Mountains ,

Some historical controversy clouds the achievements of Antoine Laumet de Lamothe Cadillac, a French adventurer who in 1701 founded the first significant European post west of the Allegheny Mountains and named it Detroit. The letters that Cadillac left behind give evidence of a spirited, determined, and ambitious man, and those written about him during his era reveal that these same qualities earned him an abundance of enemies.

The very name "Cadillac" was mired in debate for many years, but historians now believe that the explorer was not of noble French birth as he claimed, but simply adopted the "Lamothe Cadillac" surname when he arrived in North America. Instead he was born Antoine Laumet in 1658 in the village of St. Nicolas-de-la-Grave in southern central France, and hailed from relatively prosperous local families on each side of his parentage; his father was a local magistrate. It is thought that Cadillac was educated at the Doctrinal College at Moissac, or perhaps at an institution in Toulouse called L'Esquile.

There is some mystery concerning Cadillac's military service as a young man that allegedly began around 1677-he claimed to have been in regiments of Dampierre-Lorraine and Clairambault, but some historians surmise he may have earned a criminal record instead during this period of his life, and hence the name change. In any case, Cadillac yearned to leave Europe and its seemingly stifling social, economic, and religious constraints behind, and looked toward the new lands across the Atlantic to which England and France were then staking claim. Fur traders, Jesuit priests, and ordinary adventurers were settling the regions of what is now New England, Canada's Maritime Provinces, and Quebec. In Cadillac's day, the exploits of the men who had first claimed these lands were legendary-such as Samuel de Champlain's founding of Quebec in 1608-and perhaps he saw for himself similar glory as a conqueror of the unfamiliar territories.

Cadillac probably first set foot on North American shores when he landed at Port Royal, Acadia (now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia) in 1683. During his residency there, he explored the coastline, made maps, and sent informative reports back to the French government. By 1687 he was involved in business dealings with a Quebec transplant named Guyon, and married the trader's daughter, Marie Therese, in June of 1687. His marriage record contains the first official appearance of the name "Lamothe Cadillac." He even appropriated another noble family's coat of arms, but historians point out that such name-changes were not unusual among the French both in Europe and the new settlements.

In 1688 Cadillac was granted land in Acadia, was made a notary and court clerk at Port Royal, and began a family. Over the next few years, Cadillac traveled frequently back to France to give official reports at Court, and won the confidence of officials in the Ministry of Marine. For many years he lobbied for an increased naval presence along the interior waters in New France, from the St. Lawrence River to the Great Lakes.

The French government named Cadillac a captain in the Marines and naval ensign in April of 1694. He was sent to command the fort at Michilimackinac, located at what is now Mackinac City, Michigan. The settlement had a Jesuit mission, villages of Ottawa and Huron Indians, and some French families. Cadillac relished the time spent there, learning much about the indigenous culture of the region. His reports back to France were translated into English in 1947, and in them he wrote detailed accounts of the tribes. "It is always healthy at Michilimackinac; this may be attributed to the good air or to the good food, but it is better to attribute it to both," Cadillac observed in an excerpt reprinted in Michigan, A State Anthology: Writings about the Great Lakes State, 1641-1981."A certain proof of the excellence of the climate is to see the old men there, whose grandsons are growing gray; and it would seem as if death had no power to carry off these specters."

Though as commander of Fort Michilimackinac Cadillac strengthened ties with the Huron and other nations already there, he also came into conflict with another influential New World presence-the Jesuit missionaries, there to convert indigenous nations to Catholicism. It is thought that Cadillac may have received some of his early schooling from teachers belonging to this order, who were known as strict disciplinarians and devout friars, and a marked hostility to the order would brand his career in North America. One point of contention was the Jesuits' desire to keep the Native American nations free from a dependency on alcohol, and they had enjoined the French king to issue royal decrees barring its trade. Yet white traders sometimes exchanged brandy for beaver pelts, and Cadillac was accused of doing so in 1695. The Jesuit posted nearby complained to Count de Frontenac, the governor-general of New France, but Cadillac was exonerated.

France still considered the savvy, intrepid Cadillac a valuable asset, and the king and royal advisors finally heeded his arguments that France should establish a trading center on the Great Lakes to compete with New York and thwart English ties with Native American nations to the West. In December of 1698 he successfully convinced Louis XIV and his Minister of Marine, Count Pontchartrain, to decree the establishment of a fort on the Detroit River. This had been planned before, but the explorer Duluth instead founded a settlement some sixty miles north near what is now Port Huron, Michigan. There was only a handful of small Indian settlements in the region, since tribes of the powerful Iroquois nation controlled territory to the south, and their enemies maintained lands near the St. Clair River.

With royal approval and funding, Cadillac departed Montreal on June 5, 1701, with a flotilla of 25 canoes and a contingent of one hundred French. Accompanying them were canoes plied by Native Americans, who served as guides. They traveled down the St. Lawrence River into Georgian Bay and Lake Huron, and then down the St. Clair River and through Lake St. Clair. On July 24, 1701, they disembarked at the narrowest point in the Detroit River where 40-foot bluffs abutted the land near what is present-day downtown Detroit; he claimed it formally in the name of the King of France. Immediately a fortification was started, which Cadillac named after his ally at Court, Count Pontchartrain. The name "Detroit" has its origins in Cadillac's naming of the "ville de troit" or "city of the straits."

As commander, Cadillac immediately established cordial relations with nearby Ottawa, Huron, Potawatomi, Miami, and Wyandotte tribes, and encouraged them to group together in villages near the fort for mutual protection against both Iroquois and English enemies. There were only a few dozen soldiers stationed at Fort Pontchartrain in its early years, and Cadillac lobbied unsuccessfully for "christianized" Indian women from Michilimackinac to be brought to Detroit as brides for the men, a plan the Jesuits opposed. Cadillac's own wife arrived in 1702, after leaving two of their daughters behind at a convent in Quebec. Madame Cadillac, along with the wife of his second-in-command, Alphonse de Tonty, made an arduous trek of almost a thousand miles in open canoe to become the first European women settlers in Detroit. Madame Cadillac also brought along their seven-year-old son Jacques.

The contentious Cadillac again earned enemies in his new post-for instance, he punished some clerks at the fort for illegal trading in 1703. When they brought counter-charges, he was summoned to Quebec to answer to them. That same year he suspected Tonty of allying with the Jesuits to establish a trading post at Port Huron. Despite these and other conflicts, the Detroit settlement grew over the next few years and began to thrive economically. The area's first officially recorded birth came with his daughter, Marie-Therese, in 1704. At least four other Cadillac offspring were born there, but three died before the age of five.

Hostilities between indigenous nations increased around 1705, threatening the stability of the Fort. Reports reached Count Pontchartrain that same year that Cadillac was defying royal decree and trading the Indians brandy for pelts. A commissioner, Francois Clairambault d'Aigremont, was dispatched to investigate. Arriving in 1707, he found Cadillac guilty of several charges, including falsification of the number of permanent households. Clairambault also reported that Cadillac possessed the only horse in Detroit and rented it out. As a result, in a 1709 issuance from King Louis XIV, Cadillac was praised for his success in establishing the fort, but the troops that held it were officially recalled back to Montreal. So was Cadillac, who was arrested there on the charges of extortion and abuse of power.

Again, Cadillac managed to outwit his detractors and instead was named governor of the territory of Louisiana in November 1710. This huge territory, centered around what is now the southeastern United States, held little interest for Cadillac, and he dallied for over two years before arriving near what is now Mobile, Alabama, in June of 1713. His governorship of the area was less than noteworthy; he had managed to interest a financier in the trade possibilities of the area, but came into conflict with him and the officials already there. Spanish settlements, hostile Native Americans, and the oppressive tropical climate added further to Cadillac's dissatisfaction with his posting. He was finally recalled to France in 1716 after many requests on his part. Not long after he and his son arrived in Paris in September of 1717, they were incarcerated at the infamous Bastille prison.

Though they were officially charged with the suspicion of speaking treasonous words, historians surmise that Cadillac's son was jailed because he and his father had made an expedition to Illinois lands to the north in 1715 and reported to the king that they had discovered vast mineral deposits. Both father and son spent six months in the Bastille, and after his release in early 1718 Cadillac reestablished ties with his allies in the Ministry of Marine. He petitioned the court for compensation for a large swath of land he claimed to have cleared in Detroit, and returned with his family to St. Nicolas-de-la-Grave.

In 1722, Cadillac was awarded a pension, rights to some of the Detroit holdings, monetary restitution, and the Cross of Saint-Louis for three decades of service to the crown in New France. That same year he sold his Detroit real estate, and with the money purchased a commission from the Crown that gave him the governorship of the nearby town of Castelsarrasin. He was inducted as mayor of the town as well, but was removed from the post by the king not long afterward. Cadillac died in Castelsarrasin in October of 1730. Though he and Marie-Therese had a total of 13 children, only three survived their father. He was buried in the cemetery of a Carmelite church, and the whereabouts of the single portrait of him remain undiscovered.