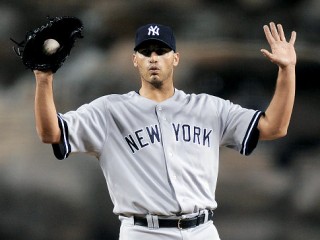

Andy Pettitte biography

Date of birth : 1972-06-15

Date of death : -

Birthplace : Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Nationality : African-American

Category : Sports

Last modified : 2010-11-06

Credited as : Baseball player MLB, pitcher with the New York Yankees,

0 votes so far

From the time he could walk, all Andy wanted to do was play catch. The Pettittes did not have a lot of money, so as Andy grew and showed promise as a pitcher, his father tried to learn everything he could about mound mechanics and strategy. By the age of seven, Andy already had developed a smooth, left-handed delivery.

When Andy was nine, the Pettittes moved west to Texas. Their new home, Deer Park, was a working class suburb of Houston. Tommy spent his days at an oil refinery south of the city, and in his spare time coached Andy’s teams in Little League and other leagues, right up through age 14.

Sometimes Tommy and Joann parents wondered if they were doing the right thing by letting Andy immerse himself so deeply in baseball. The youngster seemed devastated whenever he lost a game, or even when he made a bad pitch in a key spot. He would replay and relive each moment, and become furious with himself.

Like most young pitchers in Texas at this time, Andy’s heroes were Lone Star natives Nolan Ryan and Roger Clemens. Clemens was just beginning to make headlines with the Boston Red Sox, but he was already a college legend for the Longhorns.

In 1986, Andy enrolled at Deer Park High School. Soon after he started classes, he met a girl named Laura Dunn. Laura would one day become Andy’s wife. He also met a man named R.D. Crumley, who took an interest in his career and eventually became like a second father to him. The two hunted together and talked about life and baseball—a ritual that continued on for many years after Andy became a pro.

At this point, Andy’s father stepped aside and became a fan, allowing varsity coach Jim Liggett to take over his son's development. By his junior year, Andy stood well over six feet and threw in the low 80s with excellent control and movement. As a senior, he led Deer Park into the state playoffs and came within one victory of the championship.

Andy was an intriguing project at this stage. He stood a beefy 6-5, had good mechanics for a lefty, and possessed a competitive streak that he kept masked under a placid expression. He did not throw hard enough to blow batters away, so he understood how to mix his pitches, changing speed and location to keep opponents off-balance. There was usually a smattering of scouts in the stands when he pitched, some from colleges and some from the pros.

During his senior year at Deer Park, Andy received a couple of attractive scholarship offers, including one from LSU. That spring, he was also drafted by the Yankees in the 22nd round. Andy actually hoped the Astros would grab him, seeing as they had sent scouts to many of his games. But the team was notorious for overlooking talent in its own backyard. Bob Watson and Art Howe, the GM and manager of the Astros at the time, remember hearing about Andy, but can’t recall why they didn’t snap him up.

Unsure of his next move, Andy and his parents decided he would spend a year at nearby San Jacinto Junior College, then either go to LSU, jump back in the draft or sign with the Yankees. San Jac had a dynamite baseball program. It was coached by Wayne Graham, who instantly recognized Andy’s competitive fire. He called the freshman a “lefthanded Roger Clemens,” which brought a wide grin to Andy’s face. Graham wasn’t just stroking Andy’s ego—he had coached the Rocket for a year at San Jac before he went on to greatness at UT.

Graham convinced Andy that it was time to think about conditioning. He put him on a diet that pared his weight down 15 pounds to 215, and created a regimen of running and lifting that transformed his body over the winter. The results were startling. Andy’s fastball went from 85 to 92 in a matter of months, and he won eight of 10 decisions that spring.

Noting the lefty's improvement, the Yankees told Andy he was ready to turn pro. Both he and Coach Graham agreed. While Andy could have let New York’s claim on him expire and then re-enter the draft, the team convinced him to take an $80,000 bonus. He could have made many times that amount had he gone back into the draft, but simply didn’t realize it at the time.

Andy went right into Rookie ball, making six starts for Tampa and finishing the summer with Class-A Oneonta. He went a combined 6-3 with an ERA under 2.00. Andy’s first full pro season in 1992 was a beauty. He pitched the entire season for Greensboro and went 10–4 with 2.20 ERA in 27 starts. Andy made a great connection with his catcher, 21-year-old Jorge Posada, who was chosen two picks after him in the draft. A converted infielder, Posada was still learning the ropes behind the plate, but had the kind of bat that would keep him rising in the farm system.

ON THE RISE

Andy's sensational campaign opened plenty of eyes within the New York organization, which had not won a coveted World Series title since th 1970s.

That fall, in the instructional league, the team’s pitching coach, Billy Connors, taught Andy a circle change. It would become a key pitch for the lefty, who had already demonstrated he could spot his fastball and curve.

The 1993 season found Andy promoted to Prince William of the Carolina League. The club was thin on talent, but with Posada as his batterymate once again, the two continued learning the ropes together as they worked their way up the ladder. Andy went 11–9 with a 3.04 ERA against upgraded competition, earning a one-start call-up to Albany, where he struck out six in a five-inning victory to finish the year at 12–9.

Andy split 1994 between Class-AA Albany and Class-AAA Columbus. His record at each stop was 7–2, with an ERA below 3.00. Andy's fastball was topping out around 90, and his control was exquisite. He tied minor league hitters in knots with his sharp curve and well-disguised changeup.

The Columbus team was loaded with talent. Andy got to know a number of future Yankee teammates, including Derek Jeter, Mariano RIvera and Russ Davis. And once again, Posada made the upward move at roughly the same time as Andy. The Yankees were creating a core of young stars they hoped would carry them to the championship some day.

The combination of Andy’s fourth good season in a row and injuries to several other prospects vaulted him to the satus as jewel in the Yankees’ pitching crown. After the '94 season, Andy asked Connors to teach him a cut fastball. His goal was to leapfrog Sterling Hitchcock, who had seen action in the majors during the past three season and was being penciled into the 1995 starting rotation.

After finishing the strike-shortened 1994 campaign in first place, the '95 Yankees were the favorites to win the AL East. Andy went to spring training assuming that he was ticketed for another season in Triple-A, so he concentrated on refining his command and showing the New York brass he would be ready when the call came. In his first intrasquad game against the Yankees’ regular lineup, Andy got so nervous when Wade Boggs stepped to the plate that he started shaking. His first pitch sailed over Boggs’ head, bringing a knowing grin to the five-time batting champ’s lips.

To his delight, Andy earned a spot on the club as a middle reliever out of spring training, but was sent back to Albany in mid-May. Manager Buck Showalter, meanwhile, was having trouble cobbling together a starting staff. Jimmy Key and Melido Perez were hurt, and Jack McDowell and Scott Kamienicki were not getting the job done early. Andy was recalled and inserted in the starting rotation at the end of May. For the next two months he was the Yankees’ best pitcher.

Andy didn’t knock anyone’s socks off, but he knocked a few bats out of hitters’ hands by coming inside to both righties and lefties. Mixing in a sinking fastball and a slider, and demonstrating great poise, he survived a rocky August to finish they year 5–1 in September and 12–9 overall. Andy was at his best in Yankee Stadium, with its ample leftfield. He also proved efficient at shutting down the enemy running game. As the Yankees battled the Baltimore Orioles down the stretch, Andy watched how veterans McDowell and David Cone handled themselves in games and between starts.

The Yankees surged down the stretch, winning 21 of 26 to capture the newly minted Wild Card spot. In the very first ALDS, New York opened a 2-0 lead over the Mariners, thanks in part to seven solid innings from Andy in Game Two. But the team’s veteran pitchers wore down against Seattle’s explosive offense, and eventually the Mariners got the better of them, taking the deciding fifth game on a two-run double by Edgar Martinez in the 11th inning. The Yankees had pinned their hopes on McDowell to close out the extra-inning game, leaving Andy’s minor-league teammate Mariano Rivera unused in the bullpen.

Andy assumed the ace’s role in 1996 under new manager Joe Torre. He honed his cut fastball to unhittable perfection under pitchign coach Nardi Contreras, mixing it liberally with his sinking heater and hard-breaking curve. Despite being nagged by elbow pain for much of the year, he notched 21 victories against just eight losses to help the Yankees win the AL East crown. Andy was assisted by Rivera, who pitched over 100 innings in relief, allowing Torre to pull his starters early and spot his situational relievers as needed.

New York blended young players like Andy, Rivera and Jeter with veterans like Boggs, Mariano Duncan, Paul O’Neill, and Tim Raines, and a few guys in their prime years, including John Wetteland, Tino Martinez and Bernie Williams. Under the steady hand of Torre, they beat Texas and Baltimore in the playoffs to win their first pennant since 1981.

Against the powerhouse Braves in the World Series, the Yankees looked like an also-ran. Andy had the honor of starting Game One in the Bronxand was in the showers by the third inning after Atlanta grabbed an 8–0 lead on their way to a 21–1 win. New York expected to have problems with All-Stars Greg Maddux, John Smoltz and Tom Glavine, but they never figured 19-year-old Andruw Jones would be such a headache. The Braves overwhelmed New York in the second game, then brought the series back to Atlanta, where they hoped to close things out.

Cone gutted out a 5–2 win in Game Three, and Jim Leyritz helped the Yankees tie the series with a dramatic home run in Game Four to set up a pivotal Game Five showdown between Andy and Smoltz. Both hurlers were brilliant, but Andy was just a little better, and the Yankees seized control of the series with a 1–0 victory. They won it all two nights later in New York, putting up three early runs and then holding on for a 3-2 victory.

Andy whittled a run off his ERA in 1997, finishing 18–7 and 2.88 as he led the Yankees to 96 wins and a Wild Card berth in the playoffs. In the ALDS against the Indians, Rivera—the team's new closer—surrendered a disastrous home run to Sandy Alomar Jr. and Cleveland won a series that had seemed firmly within New York's grasp. Andy deserved much of the blame for the club ’s postseason collapse. He made two starts and pitched ineffectively as he tried to overcome a sore back that had nagged him since September. When the pain flared, he couldn’t keep his pitches down, and Tribe hitters feasted on his fastball.

MAKING HIS MARK

Despite his late-season woes, Andy had made believers out of everyone in baseball. He had “it”—that mound presence that boosted his teammates performance and sapped confidence from opponents. Andy threw hard enough to notch strikeouts when he needed them, but was economical enough to give the team enough innings to get to the finishing duo of Ramiro Mendoza and RIvera. When Andy did allow baserunners, they usually stayed put. His pickoff move was the best in a generation.

The 1998 season was a record-breaking one for the Yankees, who finished with 114 wins and were virtually untouchable from start to finish. Williams won the batting title and Jeter led the league in runs, but this was hardly a team of superstars. It was a group that executed beautifully and knew what it took to win. Ironically, Andy had a tough year. In this atmosphere of near perfection, his competitive fire often got the best of him. When he served up a bad pitch or gave up a cheap hit, he beat himself up and often lost his focus. His ERA soared and he won only 16 games. Late in the year, he stopped trusting his cutter, and enemy hitters went to town. Still, when it was all said and done, Andy had 67 wins in his first four big-league seasons—more than anyone else in the league during that time.

Come playoff time, Andy seemed his old self again, handcuffing the Rangers during an opening-round sweep. Against the Indians in the ALCS, however, he failed to win crucial Game Three, unable to overcome a brain cramp by second baseman Chuck Knoblauch, who let two runs score while arguing a play at first base. Fortunately, the Yankees rebounded to win the series.

With a wealth of starting options, Torre was able to hold Andy back against the San Diego Padres in the World Series until Game Four. His dad was undergoing double-bypass surgery and Andy wanted to be at his side. The operation was a a success, and Andy returned to the team in time for his start. By this time, the Yankees were ahead three games to none. Andy took the ball and completed the sweep, throwing shutout ball into the eighth inning before handing the game over to Jeff Nelson and Rivera, who closed it out.

The 1999 Yankees had to work for it, but they won the AL East again. Andy started the year on the DL. When he returned, he began overusing his cutter. Righthanded hitters, looking for pitches on the inside half, began drilling the ball to left against him, and his ERA climbed above 5.00. With the sluggish start, the vultures began circling. Teams in need of pitching made the Yankees some appealing offers, and almost every day that spring the tabloids had Andy on the verge of leaving town. But Torre put his foot down and George Steinbrenner listened to him—Andy was staying put. The second half was vintage Pettitte. Mixing his pitches better, he went 9-4 to finish strong with 14 victories.

The Yankees entered the postseason favored to make it two straight championships. Andy bedeviled the Rangers again in an ALDS sweep, then outpitched Bret Saberhagen in Game Four of the ALCS against the Boston Red Sox. New York won the series in five to set up a rematch with the Braves for all the marbles.

This time it was Atlanta that looked overmatched. They were swamped in the first two games, but battled back against Andy in Game Three to take a 5–2 lead headed into the eighth. Andy was on the bench when his teammates staged a great comeback, capped off by dramatic homers by Knoblauch and Chad Curtis for a 6–5 win. Clemens, the newest Yankee hurler, finished off the Braves one night later to earn his first World Series ring.

The addition of The Rocket to New York’s pitching staff had been a major thrill for Andy. The two Texans became fast friends. Andy watched in awe as Clemens extended a streak he had begun with the Blue Jays a year earlier to win an AL-record 20 straight. When hamstring problems slowed Clemens down, Andy picked up the slack. He also helped the veteran deal with the unique pressures experienced by superstars in pinstripes. After the season, Andy gladly signed a new $25 million dollar deal to stay in New York for three more seasons.

In 2000, Andy and Clemens gave the Yankees the one-two Lone Star punch they were after, combining for 32 wins in 64 starts in a year that saw the team struggle to win the division. Andy won 19 times thanks to some outrageous run support, plus Rivera, who managed to hold together the least dependable pitching staff of Torre’s Yankee tenure. The offense was helped by the blossoming of Posada and late-season trades for Glenallen Hill and Dave Justice, but it was nip and tuck with the Blue Jays and Red Sox right into September.

In the playoffs, Andy shutout the Oakland A’s with help from Rivera in Game Two of the ALDS, then left Game Five with a lead that the bullpen protected for him, as New York advanced to the ALCS. Against the powerhouse Mariners, the Yankees split the first two games at home, then gave Andy the ball for Game Three in Seattle. He beat the M’s 8–2—his fifth straight winning decision in postseason play—and New york went on to win the pennant in six games.

Against the crosstown Mets in the 2000 Subway Series, Andy started the opener and Game Five. Though he pitched well both times, he came away empty-handed. The Yankees won each of his starts, however, to take their third straight championship, four games to one.

Andy continued his stellar pitching in 2001, running his record to 14–6 by mid-August. The 28-year-old lefty had added a four-seam strikeout pitch to his repertoire, while simultaneously keeping his walks down to just one or two a game. There was talk of a Cy Young award for Andy, so when he hit a rough patch no one paid much attention. Besides, the Yankees had all but sewed up the division at this stage. Soon, however, a rumor began circulating that Andy was tipping his pitches. In September, he was nailed above the left elbow with a line drive and failed to pitch consistently after that. He finished 15–10, but his ERA in the last six weeks was double what it had been before that.

Andy pulled himself together for the playoffs. Torre handed him the ball a Game Two of the ALDS, but the A’s hung a loss on him despite a good effort. Fortunately, the Yankees won the next three straight to advance to an ALCS showdown with the Mariners. Andy won the opener 4–2, and closed out the series with a 12–3 victory in Game Five for New York’s fourth consecutive pennant.

The Yankees faced the Diamondbacks in the World Series. Andy lost an exciting Game Two duel with Randy Johnson, then returned to the mound in Game Six with a chance to put the series away. But Arizona hammered him enroute to an embarrassing 15–3 blowout. The loss proved devastating as the D-Backs scratched out a ninth-inning victory in Game Seven to snatch the championship from New York’s grasp. No one was sure what to make of Andy’s season—least of all Andy, who went through a long winter knowing he had come up short when he was counted upon most.

In 2002, Andy hit the DL after just three starts with a sore elbow. He did not get his second win until the last day of June, causing many fans to write him off. Andy rebounded brilliantly, however, finishing with 13 victories against five losses and a staff-best 3.27 ERA. The Yankees, powered by newcomer Jason Giambi and explosive Alfonso Soriano, won 103 games and charged into the playoffs looking for their fifth world championship in seven seasons.

It was not to be. After Williams beat Anaheim with a home run in Game One of the ALDS, the Halos decimated New York pitching and scored three straight comeback victories—one at Andy’s expense—to dump the Yankees. Despite his poor postseason performance, the Yankees exercised their option on Andy for one more season in New York.

The Yankees recovered to capture the division again in 2003, with Andy proving to be one of the difference-makers. The hard-hitting Red Sox challenged New York, but the Yankee pitching was just too good. Andy went 21–8 to lead the staff, overcoming a sluggish start to win 16 of his final 18 decisions. With hitters still expecting his cutter in key situations, Andy usually went to his heater, which had actually gained velocity since his elbow woes of the previous year. He fanned 180 batters while walking just 50—the seventh best ratio in the league.

Andy continued his solid pitching in the postseason, beating the Minnesota Twins in Game Two of the ALDS and the Red Sox in Game Two of the ALCS. Andy also started Game Six against Boston, but could not quiet the Beantown bats. He left the game on the winning side of a 5–4 score, but the bullpen blew it, forcing the now-famous Game Seven in which the Yankees won the pennant on clutch hits by Posada and Aaron Boone.

The '03 World Series found the Yankees playing the surprising Florida Marlins. The fans in the Bronx were overconfident at the start of Game One, which the Yankees dropped 3–2. They felt better when Andy shackled the Marlins 6–1 n Game Two. Mike Mussina next beat the Fish by the same score, but the Marlins knotted the series with a 12-inning win the next evening.

Florida squeezed out another improbable win in Game Five, and suddenly New York’s back was against the wall. As he had done so often, Torre handed the ball to Andy. He took the mound in Yankee Stadium and gave a command performance, allowing the Marlins just two runs, one of which was unearned. But fireballer Josh Beckett, who had pitched well in the loss to Mussina, came back on three days rest to twirl a five-hit complete-game shutout.

That winter, Andy was a free agent. The smart money had him returning to the Yankees. But with Clemens announcing his retirement and the tug of family stronger than ever, there was less to keep him in the Big Apple than people thought. Even Steinbrenner’s millions could not persuade him, though some thought the Boss short-changed Andy on his offer. He wound up signing a three-year deal with the Astros for less—the so-called hometown discount.

Houston had finished a game short of the Wild Card in 2003 thanks to great seasons from some mediocre starters. Owner Drayton McClain was not interested in defying the odds again. With a bullpen full of great young arms, he had decided to let closer Billy Wagner leave via free agency and spend the money on starters to help ace Roy Oswalt. Andy seemed like just the man the team needed. When Clemens unretired to join his friend on the Houston staff, the city began crackling with excited talk of a World Series.

And no wonder. The Astros had a powerful offense tailored to its cozy ballpark. The Killer Bs—Craig Biggio, Jeff Bagwell and Lance Berkman—and Jeff Kent led the way, and the team had a solid bench. It seemed that all the stars were aligned for the ’Stros.

Andy had swung the bat from time to time in interleague play, but as a National Leaguer, he would be expected to fulfill the duties of a ninth-place hitter. He was not particularly skilled at the plate, a deficiency that became clear in his first game, when he strained his left elbow on a checked swing. The soreness this injury caused landed him on the DL, and when he came back he strained his forearm. Andy’s physical problems seemed minor compared to what the team was enduring. They were struggling to get to .500, and the St. Louis Cardinals were running away with the division.

Andy tried to come back in July and pitched fairly well through the pain, but eventually he had to be shut down and undergo season-ending surgery. He watched as new manager Phil Garner rallied his troops to a remarkable Wild Card run, fueled by mid-season pickup Carols Beltran and Clemens, who pitched brilliantly all year.

The Astros outlasted the Braves in the Division Series and nearly beat the Cardinals in the NLCS. Andy’s replacement, Brandon Backe, pitched extraordinarily well under pressure, giving the team hope for a powerhouse staff in 2005.

The pitching was indeed good the following season, but there were big questions on offense. Bagwell was incapacitated by a career-ending shoulder injury, Beltran had signed a free agent deal with the Mets, and Berkman blew out his knee playing pickup basketball in the off-season. Although Andy was healthy and Clemens returned for another season, the Astros were 15–30 and seemingly dead in the water after 45 games.

Buoyed by the rehabbed Berkman and breakout years by youngsters Morgan Ensberg, Jason Lane and Willy Taveras, the Houston offense got in gear. Meanwhile, Andy combined with Oswalt and Clemens for 50 wins, enabling the Astros to snag the Wild Card for the second year in a row. The last team to fall 15 games under .500 and make it to the postseason? The 1914 Miracle Braves.

The Miracle Astros made some history of their own, ambushing the Braves in the NLDS with help from Andy, who won the opener. In their NLCS rematch with the Cardinals, Houston again beat the odds, winning three of the first four contests to set up the clincher for Andy. He pitched six strong innings, and the Astros went into the ninth with a 4–1 lead. The usually unhittable Brad Lidge allowed two baserunners in the final frame, then gave up a game-winning bomb to Albert Pujols to give the Cardinals life and send the series back to St. Louis. Luckily, Oswalt saved one of his best all-time starts for the Redbirds, and Houston advanced to its first World Series in franchise history.

The Astros met the White Sox for all the marbles. Four frustrating games later it was all over— Chicago each contest, capped by a 1–0 victory in the finale. Each game was close, but the White Sox got the big hits when they were needed and the Astros did not. Andy got a no-decision in his only start.

Despite its heartbreaking outcome, the '05 season was a good one for Andy. He went 17–9 with a microscopic 2.39 ERA in a hitter’s park, and logged 222 innings less than a year after arm surgery.

Andy and the Astros were poised for another run at the championship in 2006. Though Clemens was a no-show in spring training, he joined the team over the summer after Houston showered him with cash. Unfortunately, many of the rest of the Astros were no-shows for the enitreyear. Lane and Ensberg could not repeat their 2005 performances, Lidge was awful, and the Astros were sinking fast.

Only in the final weeks did the team pull together, but their great September run fell one game short of the Cards, who went on to win the World Series. Andy bounced back with a solid 14-13 record, and his 178 strikeouts were the second most of his career.

Still, as the off-season rolled around and his contract with the Astros expired, Andy wondered whether he had enough in the tank to pitch another season. He had been contemplating retirement for more than a year, and for a while the stars seemed to be pointing that way. In November he told reporters he was thinking about calling it quits. The Astros tried to talk him out of it, as did the Yankees, who realized they had lost something special when he had left the team. In December, Andy decided to give it another year—back with Torre and the Yankees. The team signed him for one year at $16 million, with a second year at Andy’s option for the same price.

Andy rejoined a staff with lots of depth and lots of talent. Chien Ming-Wang, Mike Mussina and later an un-retired Roger Clemens helped pitch the Bronx Bombers into the playoffs—albeit as a Wild Card. Andy delivered as expected, leading the AL in starts and finishing among the Top 10 in innings pitched. He registered 15 victories against nine defeats.

In the Division Series against the Indians, Wang got blown out in Game 1, but the Yankees were confident sending Andy to the hill for Game 2. He was brilliant against young Fausto Carmona and left the game with a 1–0 lead. But Joba Chamberlain allowed the tying run in the famous “bug” incident, and Cleveland went on to win in extra innings. The Tribe took the series in four games, chasing Wang again in the finale. Many fans questioned the wisdom of giving him two starts instead of Andy.

The startling defeat was actually New York’s third straight ALDS exit in a row. That was enough to convince the Yankees to end the Joe Torre era. Joe Girardi, Andy’s old catcher, was named manager over Don Mattingly. Andy flirted briefly with free agency after the season but returned to the Bronx.

At roughly the same time, Andy admitted to having used human growth hormones to help heal an injury in 2002 and again in 2004. He was adamant, however, that he had not used steroids or any other performance-enhancer. Later he stated in an affidavit that he recalled Clemens taking HGH injections. The Rocket steadfastly refused to any admission about HGH or steroids and famously said that his friend had “misremembered.” Clemens added that his wife had been using HGH and that Andy might have been confused. At spring training in 2008, Andy held a press conference and apologized publicly.

Although Andy had a solid season in 2008, the year was a dismal failure for the pinstripers. They found themselves looking up at the Red Sox and Tampa Bay Rays in the AL East and missed the playoffs for the first time since the mid-1990s. His 14–14 record reflected a so-so year for the team, but he made his starts and finished with 200-plus innings for the fourth year in a row.

The Yankees moved into a new stadium and revamped their pitching staff for 2009. C.C. Sabathia and AJ Burnettnow headed up the rotation, followed by Wang and then Andy as fourth starter. A free agent again, he re-signed with the Yankees, choosing a risky, incentive-laden deal instead of a steep pay cut. It was a wise move. Andy was solid all year, going 14–8 in 32 starts and rising to the three-spot after Wang went down with a season-ending injury.

The Yankees topped the 100-win mark and sailed through the playoffs against the Twins and Angels. In the Division Series, Andy beat Minnesota in Game 3 with six-plus innings of three-hit ball. He logged two starts in the ALCS. His first came in the exciting 11-inning victory in Game 3. Andy then got the win in the Game 6 clincher, limiting Anaheim to one run in New York’s 5–2 triumph.

In the World Series against the Phillies, Andy started the pivotal Game 3 in Philadelphia with the series tied 1–1. Yankee fans started to sweat when he gave up three runs in the second frame, but he shut down lefties Chase Utley, Ryan Howard and Raul Ibanez, and the Yankees clawed their way back to an 8–5 win. The victory was his 17th in the postseason, adding to his all-time record in that category. He also collected his first postseason RBI during the game.

Andy took the hill again in Game 6, with the Yankees up in the series. He had won the clinchers in the ALDS and ALCS—and had 17 career postseason victories to his credt. There wasn’t the least bit of fear or nervousness in him. Throwing on three days rest, Andy didn’t have his best stuff, but he pitched around six walks and left in the sixth with a 7-3 lead. That's how it ended. The Yankees had their 27th championship. Andy was elated.

Back in his old uniform, it is not a stretch to say that Andy could be a Hall of Famer some day. Andy has 229 career wins and a .629 winning percentage. His postseason resume is impressive as well. Is that enough to make him an immortal? That's up for debate, though not in the minds of New Yorkers.

ANDY THE PITCHER

When the Yankees let Andy leave for Houston in 2004, many lamented that it marked the end of an era. And it did. The Yankees did not reach the World Series during his absence. It took many years and millions of dollars to reach the pinnacle again, but as any loyal Yankee fan will tell you, it wouldn’t have happened if New York hadn’t brought "Big Game Andy" back.

Andy has mastered the art of being around the plate but not over it, meaning most of the time enemy hitters are swinging at his pitch. As his strikeout-to-walk ratio suggests, he rarely gives in. If a hitter is going up to the plate hoping to hit an opposite-field flair or pull one down the line, he’s likely to see a pitch he can handle. If he’s looking to take Andy out of the park, he may have a season- or career-long wait, particularly if he is left-handed.

Andy has never minded pitching with runners on base. That’s partly because his has an uncanny ability to make a great pitch in a big spot. But it's also because of his calling-card pick-off move. Only a few base stealers have been able to read it. Most just stay anchored to the bag until a teammate moves them along.