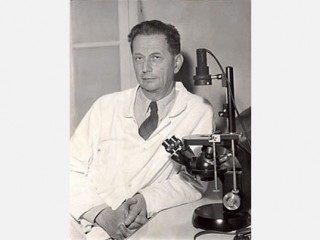

Andre Lwoff biography

Date of birth : 1908-05-08

Date of death : 1994-09-30

Birthplace : Ainay-le-Chateau (Allier), France

Nationality : French

Category : Science and Technology

Last modified : 2010-11-29

Credited as : Microbiologist and geneticist, European Organization of Molecular Biology , won the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1965

The French microbiologist, protozoologist, and geneticist André Lwoff (1902-1994) was influential in the creation of the European Organization of Molecular Biology in 1964.

André Lwoff, born May 8, 1902, at Ainay-le-Chateau (Allier), was the son of Russian parents recently settled in France. He studied science and medicine at the University of Paris and was attached to the Pasteur Institute from 1921, becoming head of the department of microbic physiology and later a professor. He performed services for which he was awarded the Médaille de la Resistance in 1964 and became commandeur of the Légion d'Honneur in 1966. He shared the Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine in 1965 for his research on episomes.

Early bacteriologists had considered bacteria to be primitive forms of life, (protista) more closely akin to animals than plants, because bacteria lacked chlorophyll and were believed to be devoid of such defined structures as nuclei and chromatin. The view that they did not possess specificity and could at times produce various diseases was disproved by Robert Koch, who established the specific lesions of pathogenic microorganisms such as Bacillus anthracis and B. tuberculosis.

When more refined and powerful methods of investigation became available and the chemistry of nucleoproteins was clarified, it became clear that certain hitherto neglected observations required attention. Among them were the spontaneous clearing of colonies of micrococci found in certain cultures recovered from a vaccine lymph by F. W. Twort (1917) and the clearing of suspensions of dysentery bacilli in an apparently sterile filtrate of the feces from a patient who had the disease by H. d'Hérelle (1917). An astonishing discovery was that when a minute quantity of the clear filtrate was added to a suspension of a fresh subculture of the same organisms, the bacteria under the microscope were seen after a short time to swell and burst, setting free tadpolelike objects that D'Hérelle considered a virus (bacteriophage or phage). According to D'Hérelle, a virus phage became adsorbed by the bacterium, penetrating and dissolving it while multiplying in the process and generating a solvent.

Lwoff adopted a suggestion of Eugène Wollman that the manifestations might be due to the action of genes. A large band of workers was attracted—over 50 are included in Lwoff's list of contributors—and he recorded and analyzed many remarkable findings in his review (1953).

In the United States, particularly, much research was stimulated.

Lwoff speaks of "lysogeny" as the faculty of certain strains of bacteria to produce phage. The production of phage is a lethal process that is survived only if the bacteria do not produce it in their hereditary constitution. The experimental evidence on which the conclusions rest is complex and need not be extended here. As it is expressed by Lwoff: "The unitary concept…provides a model to which all the properties of Iysogenic bacteria are ascribed. This unitary concept is accounted for by the presence and position of a specific structure representing the genetic material of the phage, the properties of a lysogenic bacterium being the consequence of the right particle at the right place. Position is the 4th dimension of the prophage. Although the unitary concept has the advantage of explaining Iysogeny, lysogenization, incompatibility, immunity and induction—all the properties of lysogenic bacteria—it is only a hypothesis and not a dogma."

Apart from the practical use of Lwoff's conclusions in "typing" strains of organisms recovered in epidemics, a justification of his views appeared later in developments such as those obtained by Shapiro and coworkers (1969), who isolated a complex of genes controlling a single function representing lactose operon.

Lwoff was professor of microbiology at the Sorbonne from 1959 to 1968. In 1968, he left the Pasteur Institute to become head of the Cancer Research Institute at Villejuif, near Paris. He retained that post until 1972.

Lwoff died in Paris on September 30, 1994, at the age of 92. He was the last surviving member of the triad that had shared the 1965 Nobel Prize. Writing in Le Monde shortly after Lwoff's death, his colleague, Dr. Claudine Escoffier-Lambiotte, praised Lwoff for his opposition to capital punishment, his love of painting, sculpture, music, and "those things that awaken the spirit." Dr. Escoffier-Lambiotte also noted that Lwoff's "total absence from conformity and diplomacy" often earned the enmity of his colleagues.

A biographical sketch of Lwoff is in Theodore L. Sourkes, Nobel Prize Winners in Medicine and Physiology, 1901-1965 1901-1965 (rev. ed. 1967); An interesting discussion of Lwoff's personality and career is in Leonard Engel, The New Genetics (1967); The book Of Microbes and Life (1971) consists of essays by former students and colleagues in celebration of the 50th anniversary of Lwoff's immersion in biology; Lwoff's obituary appeared in the New York Times on 4 October 1994.