Ana Pauker (En.) biography

Date of birth : 1893-02-13

Date of death : 1960-06-03

Birthplace : Vaslui, Romania

Nationality : Romanian

Category : Historian personalities

Last modified : 2010-05-09

Credited as : Communist leader, Foreign minister of Romania, Soviet Union

0 votes so far

Early life and political career

Pauker was born into a poor, religious Orthodox Jewish family in Codăeşti, Vaslui County (the region of Moldavia). Her parents, Ukrainian Jews Sarah and (Tsvi-)Hersh Kaufman Rabinsohn, had 4 surviving children; an additional two died in infancy. As a young woman, she became a teacher. While her younger brother was a Zionist and remained religious, she opted for Socialism, joining the Romanian Social Democratic Party in 1915 and then its successor, the Socialist Party of Romania, in 1916. She was active in the pro-Bolshevik faction of the group, the one that took control after the Party's Congress of May 8–12, 1921 and joined the Comintern under the name of Socialist-Communist Party (future Communist Party of Romania). She and her husband, Marcel Pauker, became leading members. They were both arrested in 1922 for their political activities and went into exile to Switzerland on their release.

Communist leadership position

Ana Pauker went to France where she became an instructor for the Comintern and was also involved in the Communist movement elsewhere in the Balkans. She returned to Romania and was arrested in 1935, being put on trial together with other leading Communists such as Alexandru Moghioroş and Alexandru Drăghici, and sentenced to ten years in prison. In May 1941 she was sent into exile to the Soviet Union in exchange for Ion Codreanu, a former member of Sfatul Ţării (Parliament of Bessarabia that voted for Union with Romania on the 27th of March 1918) detained by the Soviets after the occupation of Bessarabia in 1940, just in time to escape the policy of oppression and massacre of Jews by the regime of Ion Antonescu, in alliance with Nazi Germany. In the meantime, her husband fell victim to the Soviet Great Purge, in 1938. Rumors abounded that she herself had denounced him as a Trotskyist traitor; Comintern archival documents reveal, however, that she repeatedly refused to do so.

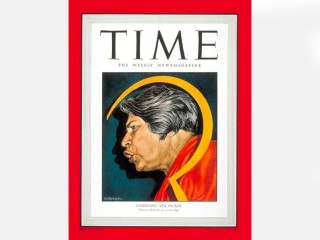

In Moscow, she became leader of the Romanian Communist exiles who would later become known as the Muscovite faction. She returned to Romania in 1944 when the Red Army entered the country, becoming a member of the postwar government, which came to be dominated by the Communists. In November 1947, the non-Communist Foreign Minister Gheorghe Tătărescu was ousted and replaced by Pauker, making her the first woman in the modern world to hold such a post. But it was her position in the Communist Party leadership that was paramount: As a member of the 4-person Secretariat of the Central Committee and formally Number Two in the leadership, Pauker was widely believed to have been the actual leader of the Romanian Communists in all but name during the immediate postwar period. In 1948 Time magazine featured her portrait on its cover, with the caption The most powerful woman alive. She was universally seen as unreservedly Stalinist and as Moscow's primary agent in Romania.

However, once in power, Pauker gradually began to take positions counter to those of the Kremlin. In 1949 she did not support the construction of the Danube-Black Sea Canal, even though, according to her own testimony, Joseph Stalin had personally proposed the project. She opposed the purging of Romanian veterans of the Spanish Civil War and French Resistance as part of Moscow's bloc-wide campaign against Josip Broz Tito, as well as Stalin's plans to have former Communist leader Lucreţiu Pătrăşcanu put on trial. She supported (and helped facilitate) the emigration of roughly 100,000 Jews to Israel from the spring of 1950 to the spring of 1952, when all other Soviet satellites had shut their gates to Jewish emigration in line with Stalin's escalating "anti-Zionist" campaign. And she firmly opposed forced collectivization that was carried out on Moscow's orders in the summer of 1950 while she was in a Kremlin hospital undergoing treatment for breast cancer. Angrily condemning such coercion as "absolutely opposed to the line of our party and absolutely opposed to any serious Communist thought", she allowed peasants forced into collective farms to return to private farming and effectively halted additional collectivization throughout 1951. This, as well as her support for higher prices for agricultural products in defiance of her Soviet "advisers", led to charges by Stalin himself that Pauker had fatefully deviated into "peasantist, non-Marxist policies".

Pauker's "Moscow faction" (so called because many of its members, like Pauker, had spent years in exile in Moscow) was opposed by the Prison faction (most of whom had spent the Fascist period, mainly under Antonescu's dictatorship, in Romanian prisons, particularly Doftana Prison). Gheorghe Gheorghiu-Dej, the de facto leader of the Prison faction, had supported intensified agricultural collectivization and was a rigid Stalinist; however, he resented Soviet influence (which would become clear at the time of de-Stalinization when, as leader of Communist Romania, he was a determined opponent of Nikita Khrushchev).

Downfall

General Secretary Gheorghiu-Dej profited from the mounting anti-Semitism in Soviet policy, and persuaded Joseph Stalin to take action against the Pauker faction. Dej traveled to Moscow to seek Stalin's approval for purging the leadership of the Romanian Communist Party, accusing Pauker, Vasile Luca, and Teohari Georgescu of fomenting factional intrigue. Soviet Foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov intervened on behalf of Pauker, whereas NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria defended Georgescu—their lives were spared Pauker and her supporters were purged in May 1952, consolidating Gheorghiu-Dej's own grip over country and Party.

Pauker was charged with "cosmopolitanism", the charge Stalin used against Jews in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc. According to biographer Robert Levy, Pauker was purged at Stalin's urging for being too soft. According to the memoirs of Silviu Brucan, former Romanian ambassador to the United Nations, Stalin told Gheorghiu-Dej that he had chosen him to lead Romania over Pauker, saying:

Ana is a good, reliable comrade, but you see, she is a Jewess of bourgeois origin, and the party in Romania needs a leader from the ranks of the working class, a true-born Romanian.… I have decided…

Pauker was arrested in February 1953 and was subjected to prolonged interrogations in preparation to be put on trial, as had occurred with Rudolf Slánský and others in the Prague Trials. After Stalin's death in March 1953 she was freed from jail and put under house arrest instead.

Following the rise of Nikita Khrushchev in the Soviet Union, Pauker was recast by Romania's leaders as having been a staunch ultra-Orthodox Stalinist, even though she had opposed or had attempted to moderate a number of Stalinist policies while she was in a leadership position. Following the Twentieth Party Congress in Moscow there were fears that Khrushchev might force the Romanian Party to rehabilitate Pauker and possibly install her as Romania's new leader.

In 1956, she was summoned for questioning by a high-level party commission, which insisted that she acknowledge her guilt. Again, she claimed she was innocent and demanded that she be reinstated as a party member, without success. Gheorghiu-Dej went on to scapegoat her, Vasile Luca, and Teohari Georgescu for their alleged Stalinist excesses in the late 1940s and early 1950s, despite the fact that they had urged moderation against Gheorghiu-Dej's insistence on dogmatism. The period when the three were in power was marked by political persecution and the murder of opponents (such as the infamous brainwashing experiments conducted at Piteşti prison in 1949-1952). Gheorghiu-Dej, who had as much to account for, used moments like these to ensure the survival of his policies in a post-Stalinist age.

During her forcible retirement, Pauker was allowed to work as a translator from French and German for the Editura Politică publishing house.