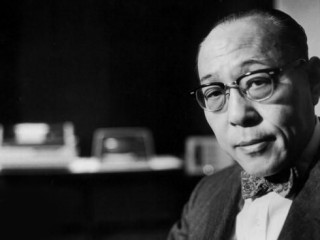

An Wang biography

Date of birth : 1920-02-07

Date of death : 1990-03-24

Birthplace : Shanghai, China

Nationality : Chinese

Category : Arhitecture and Engineering

Last modified : 2010-11-26

Credited as : Computer engineer and inventor, founder of Wang Laboratories Incorporated, invetions of computer memories and to electronic calculators

An Wang made important inventions relating to computer memories and to electronic calculators. He was the founder and longtime executive officer of Wang Laboratories Incorporated, a leading American manufacturer of computers and word processing systems.

An Wang was born February 7, 1920, in Shanghai, China. He became interested in radio as a high school student, built his own radio, and went on to study communications engineering at Chiao-Tung University in his native city. After graduation he stayed on at the university another year as a teaching assistant. With the outbreak of World War II Wang moved to inland China, where he spent the war designing radio receivers and transmitters for the Chinese to use in their fight against Japan.

Wang left China in the spring of 1945, receiving a government stipend to continue his education at Harvard University in Massachusetts. He completed his master's degree in communications engineering in one year. After graduation, he worked for an American company for some months and then for a Canadian office of the Chinese government. In 1947, he returned to Harvard and rapidly completed a doctorate in engineering and applied physics. Wang married in 1949, and he and his wife had three children. Six years later Wang became an American citizen.

In the spring of 1948 Howard Aiken hired Wang to work at the Harvard Computation Laboratory. This institution had built the ASSC Mark I, one of the world's first digital computers, a few years earlier. It was developing more advanced machines under a contract from the U.S. Air Force. Aiken asked Wang to devise a way to store and retrieve data in a computer using magnetic media. Wang studied the magnetic properties of small doughnut-shaped rings of ferromagnetic material. He suggested that if the residual magnetic flux of the ring was in one direction, the ring might represent the binary digit 1. Flux in the opposite direction could represent 0. One could then read the information stored in a ring by passing a current around it. Researchers at the nearby Massachusetts Institute of Technology and elsewhere were intrigued by the idea of magnetic core storage of information and greatly refined it for use in various computers. Wang published an account of his results in a 1950 article coauthored by W.D. Woo, another Shanghai native who worked at Harvard. He also patented his invention and, despite a protracted court fight, earned substantial royalties from International Business Machines and other computer manufacturers who used magnetic core memories. These cores were a fundamental part of computers into the 1970s.

Wang was not content to have others develop and sell his inventions. In 1951 he left the Computation Laboratory and used his life savings to start his own electronics company. He first sold custom-built magnetic shift registers for storing and combining electronic signals. His company also sold machines for magnetic tape control and numerical control. In the mid-1960s Wang invented a digital logarithmic converter that made it possible to perform routine arithmetic electronically at high speeds and relatively low cost. Wang desktop calculators were soon available commercially, replacing traditional machines with mechanical parts. Several calculators operated on one processing unit. These early electronic calculators sold for over $1,000 per keyboard. They were used in schools, scientific laboratories, and engineering firms. By 1969, Wang Laboratories had begun to produce less expensive calculators for wider business use. However, Wang saw that the introduction of integrated circuits would allow competitors to sell electronic handheld calculators at a much lower price than the machines his company offered.

Confronted with the need to find a new product, Wang directed his firm toward the manufacture of word processors and small business computers. The first Wang word processing systems sold in 1976. They were designed for easy access by those unfamiliar with computers, for broad data base management, and for routine business calculations. In addition to such computer networks, the company developed personal computers for office use.

Wang began his business in a room above an electrical fixtures store in Boston with himself as the only employee. By the mid-1980s the company had expanded to over 15,000 employees working in several buildings in the old manufacturing town of Lowell, Massachusetts, and in factories and offices throughout the world. To acquire money to finance this expansion and to reward competent employees, Wang Laboratories sold stock and acquired a considerable debt. The Wang family retained control of the firm by limiting administrative power to a special class of shareholders. In the early 1980s when company growth slowed while debt remained large, Wang made some effort to reduce his personal control of the business and follow more conventional corporate management practices. While remaining a company officer and leading stockholder, he gave increased responsibilities to his son Frederick and to other managers. Wang intended to devote even more time to educational activities. He served as an adviser to several colleges and as a member of the Board of Regents of the University of Massachusetts. Wang also took a particular interest in the Wang Institute of Graduate Studies which he founded in 1979. This fully accredited school gives advanced degrees in software engineering. Difficult times in the computer industry soon led Wang to turn his concentration from these projects and resume full-time direction of Wang Laboratories.

In the last decades of the twentieth century, Wang's economic structure teetered. In 1982 the organization generated more than a billion dollars a year, and by 1989 sales were $3 billion a year. But Wang Laboratories fell on hard times as well. In the early 1990s the former minicomputer maker fell into Chapter 11 bankruptcy and Wang died of cancer in March of 1990 at the age of 70.

On Jan. 30, 1997, the Eastman Kodak Company bought the Wang Software business unit for $260 million in cash. The deal put Kodak into the document imaging and workflow business and took Wang out of software. Wang also began an affiliation with Microsoft, and Michael Brown, chief financial officer for Microsoft, sat on Wang's board of directors. The reorganization enabled the company to prosper once again.

Wang's engineering acumen and business success resulted in him being made a fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers and a fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He received an honorary doctoral degree from the Lowell Technological Institute.

Wang, with Eugene Linden, published Lessons: An Autobiography in 1986. For brief accounts of his career see "The Guru of Gizmos," TIME (November 17, 1980) and "Wang Labs' run for a second billion: One-man rule will fade into professional management," Business Week (May 17, 1982). On the history of magnetic core memories see E. W. Pugh, Memories that Shaped an Industry (1984). On electronic calculators see H. Edward Roberts, Electronic Calculators, edited by Forrest M. Mimms III (1974). Wang is also included in Historical Dictionary of Data Processing: Biographies, by James Cortada (1987). The Wall Street Journal covered the fall and resurgence of Wang Laboratories in two articles, Steep Slide: Filing in Chapter 11, Wang Sends Warning to High-Tech Circles (Aug. 1992), and Wang Labs Reorganization is Cleared, Allowing Emergence from Chapter 11 (Sept. 1993).